Alliteration: Definition, Meaning, and Examples

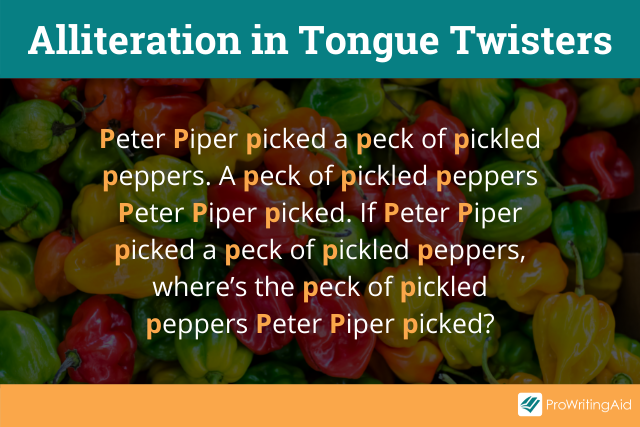

Many kids know the sentence “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” What makes tongue twisters like that one so catchy and successful?

The answer is a literary device called alliteration. The repeated “p” sounds catch our ear and create an enjoyable rhythm.

Alliteration is often used in literature, copywriting, poetry, and more.

Read on to learn what alliteration is and how to use it in your own writing.

What Is Alliteration?

Alliteration is a literary device using the repetition of consonant sounds.

Usually, the sound is the first consonant of a word repeated in two or more words or syllables.

What Does Alliteration Mean?

To create alliteration in your text, you need two or more words that begin with the same sound.

Here’s an example of alliteration with a “c” sound:

- The capable, careful carpenter.

Here’s an example of alliteration with “w” and “th”:

- Wild and woolly, threatening throngs.

Alliteration is all about sound, not just letters. For example, a hard “c” or a ”k” work equally.

This means that two words beginning with the same letter, but not the same sound, are not alliterative. Here is an example of two words beginning with the same letter that are not alliterative:

- Charming captain

Even though both words start with the letter “c,” the sounds are different so they are not alliterative.

Why Do Writers Use Alliteration?

As a literary device, alliteration focuses the reader’s attention on a particular section of text. The sounds create rhythm and mood, making that passage of text easier for readers to remember.

In addition, different consonants have particular connotations. For example, the hissing sound of the letter “s” suggests a snake-like quality, implying slyness or danger. It is the sound of a slithering snake slipping and sliding over the ground.

Recent studies demonstrate that various sounds, like those of consonants, have inherent emotional qualities for English speakers.

What bards and poets have known for millennia is now confirmed by science. Your use of repetitive sounds in alliteration creates emotional responses in your reader.

Alliteration is also useful for educational purposes, because it fosters a love of language and appreciation for the sounds of words.

Children learn language through tongue twisters and nursery rhymes that use alliteration.

Tongue twisters that use alliteration include:

- She sells seashells on the seashore.

- How much wood could a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could chuck wood?

- Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.

How to Use Alliteration Correctly

There are times when alliteration is the right choice.

It can be useful when you’re writing short pieces for adverts, or when you’re naming a character, product or business. Dunkin’ Donuts, PayPal, Best Buy, Coca-Cola—lots of successful brands use alliteration to make their names memorable.

But in most works of fiction, instances of alliteration can seem forced and disrupt the flow of your story. Overusing it can distract your readers from what’s important.

Here are our favorite tips for when to use alliteration and how to do it well.

Tip #1: Use Alliteration When You Want Emphasis and Impact

When writing prose, alliteration, used carefully, creates an impact for important sentences. Repeating consonants helps the phrase or sentence stand out, emphasizing its significance.

For example, in business writing, you may emphasize the importance of a report or concept.

Here are some examples:- ABC Piping’s proposed solution is cost-effective, commercially astute, and convincing.

The repetition of the “c” consonant sound stresses the importance of considering the proposal.

- ...this concept of creating valuable content to attract customers and build credibility has undoubtedly gone mainstream.

Again, the “c” consonant sound emphasizes the importance of the sentence.

You can also use alliteration to grab the reader's attention in a headline or the subject line of an email.

Here are some example headlines that make use of alliteration:

- Pack Your Prose with Persuasion

- 10 Sanity-Saving Tricks to Stop Clutter

- Build Your First Business Starting from Scratch

Here are some example email subject lines that make use of alliteration:

- 10 Common Cholesterol Mistakes

- Keep Calm and Craft On

- 6 Suggestions for Streamlining Your Workload

Character names are also a great place to use alliteration. Some famous examples include Mickey Mouse, Peter Parker, and Donald Duck. All three have the same consonant sound at the beginning of their first and last names, making them easy to remember.

Ultimately, you should confine your use of alliteration to emphasize important sentences and concepts. Overuse of alliteration not only dilutes its power, but makes the prose sound forced and artificial. Save alliteration for the points you want to stress.

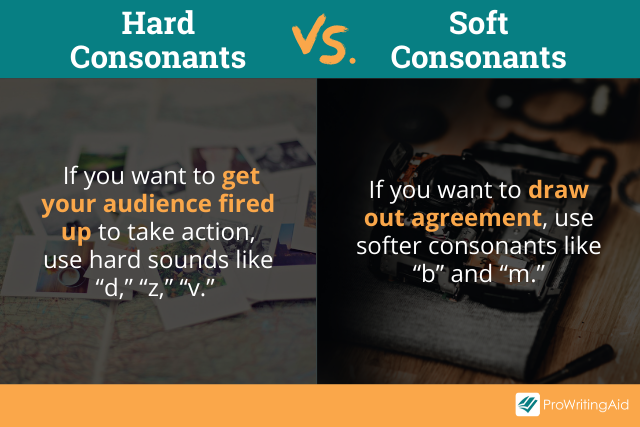

Tip #2: Match the Sound to the Mood

Different consonant sounds can create emotional responses in readers, which you can then use to elicit subtle responses.

Sounds that have negative connotations may trigger a reader to take action. Sounds that have positive connotations generate good feelings about your topic.

- Consonants that trigger a positive response: b, p, m, n

Use words like become, benefit, popular, process, magnetize, need.

- Consonants that trigger a negative response: d, t, g, k, z, v, s, f

Use words like dash, decide, take, toll, glare, keep, zip, verify, scrutinize, fail, fight.

So if you want to get your audience fired up to take action, use hard sounds like “d,” “z,” “v.” And if you want to draw out agreement, use softer consonants like “b” and “m.”

Tip #3: Utilize ProWritingAid’s Alliteration Report

When you’re writing prose, you may not even realize you've used alliteration. It’s only when you read your text back that you realize it’s there.

It’s useful to scan your document for alliteration to make sure you've used it intentionally without distracting your reader.

ProWritingAid’s Alliteration Report will highlight all the alliterative words in your text.

You can navigate the alliteration highlights within your text using the menu to the left. It’s useful for reviewing the alliteration in your writing to make sure it doesn’t sound unnatural or seem unnecessary.

Running the Alliteration Report helps you strike the right balance between a memorable turn of phrase and a distracting diversion.

Alliteration Examples

Since Beowulf, storytellers have used alliteration to emphasize important parts of their story and create memorable lines an audience does not forget.

Let’s look at examples of alliteration in English literature and poetry.

Examples of Alliteration in Literature

“Up the aisle, the moans and screams merged with the sickening smell of woolen black clothes worn in summer weather and green leaves wilting over yellow flowers.”—Maya Angelou, I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings

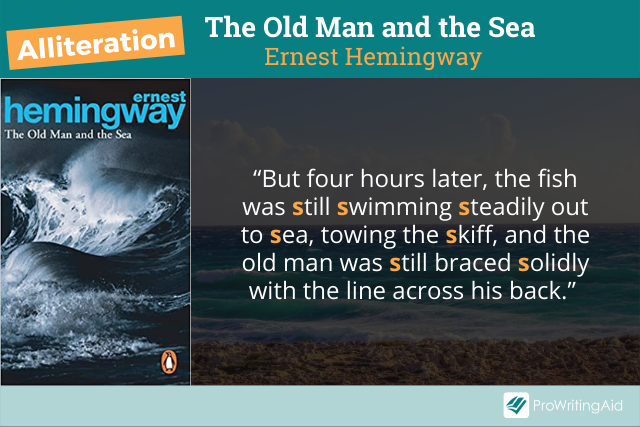

“But four hours later, the fish was still swimming steadily out to sea, towing the skiff, and the old man was still braced solidly with the line across his back.”—Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea

“... the first unknown phantom in the other world; neither of these can feel stranger and stronger emotions than that man does, who for the first time finds himself pulling into the charmed, churned circle of the hunted Sperm Whale.”—Herman Melville, Moby Dick

“A moist young moon hung above the mist of a neighboring meadow.”—Vladimir Nabokov, Conclusive Evidence

Examples of Alliteration in Poetry

In poetry, alliteration is also called head rhyme or initial rhyme. The sounds begin with adjacent words or syllables to create the repetitive pattern.

Specific sounds can affect the mood of a poem. Alliteration can give a poem a calm, smooth feeling or a loud, harsh one. It all depends on the consonants you use to make hard or soft sounds.

Alliteration can be as intense as Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty,” where the alliterative phrases mimic the contrasts of pied colorings in nature. Read this poem aloud to get the feel of how the multiple alliterations work.

Glory be to God for dappled things—

For skies of couple-color as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced—fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

“The Fury of Aerial Bombardment” by Richard Eberhart uses alliteration to cry out against senseless death.

Was man made stupid to see his own stupidity?

Is God by definition in different, beyond us all?

Is the eternal truth man’s fighting soul

Wherein the Beast ravens in its own avidity?

Finally, American poet laureate Juan Felipe Herrera uses alliteration in “Five Directions to My House” to call out the feel of the Red Tail Hawk flying and roosting.

Blow, blow Red Tail Hawk, your hidden sleeve—your desert secrets.

What are your favorite examples of alliteration? Let us know in the comments.