Anaphora: Definition & Meaning (with Examples)

You’re likely familiar with the famous lyrics to Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town.

You better watch out

You better not cry

You better not pout…

One reason the lyrics are easy to remember is because they are an example of a literary device called anaphora, the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of consecutive sentences.

Anaphora adds emphasis and emotion to words, and also makes them more memorable.

Anaphora Definition

Anaphora is the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive phrases, clauses, or sentences. That repetition is intentional and is used to add style and emphasis to text or speech.

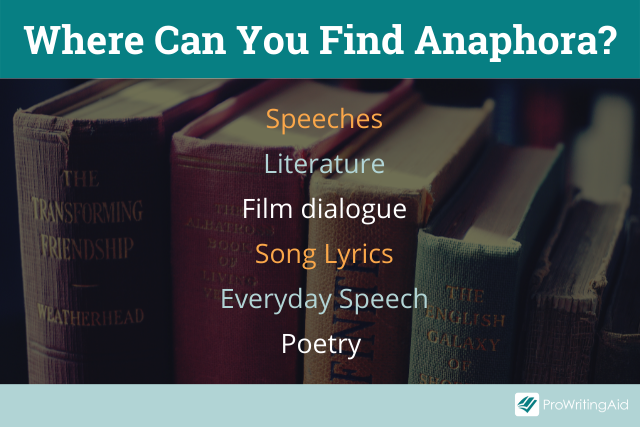

Because anaphora affects both meaning and style, you’ll find examples of it in poetry, prose, dialogue, speeches, and song lyrics. It’s a literary device with the power to emphasize meaning, add emotion, and create a sense of rhythm.

Anaphora Meaning

It’s important to remember that the repetition in anaphora is a stylistic choice. Unintentional repetition can make writing dull. Anaphora is intentional. It’s used to add meaning to words.

For example, imagine you’re reading a narrative essay about the writer’s vacation. The paragraph states:

We went to the beach. We went into the ocean. We went to the beachside bar for drinks. We returned to the hotel and took a nap. We went out later and had a fun night.

Is this repetition an example of anaphora? Technically, the answer is yes.

But if the writer is trying to dazzle us with the beauty and excitement of this vacation, the repetition does the opposite. In this case, starting each sentence the same way feels lazy.

But what if the author was trying to convey a sense of boredom? Maybe he found this seemingly relaxing vacation terribly dull and wants to convey that within the tone of his retelling.

Then he’s made an intentional, stylistic choice demonstrating both the definition and purpose of anaphora.

ProWritingAid can help you ensure your repeated words are meaningful through its All Repeats Report. It highlights repeated words and phrases so you can eliminate unintentional repetition that makes your writing dull.

Try it with a free ProWritingAid account.

Anaphora Examples

Some of the most famous speeches in history, some of the most well-known works of literature and film, and some of the most memorable song lyrics, include this literary device.

Here are a few examples:

Anaphora in Speeches

In his “I Have a Dream” speech, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. repeated the words “I have a dream” at the start of five consecutive sentences. With each repetition, the intensity of his belief and the inspiration of his words increased.

(See if you can find a second example of anaphora in this excerpt):

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state, sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

(Second example: sweltering with)

In his “We Shall Fight on the Beaches” speech, Winston Churchill uses anaphora to inspire commitment and emphasize his belief in the battle against Nazi Germany.

“We shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills. We shall never surrender.”

In his 1999 speech at the White House, “The Perils of Indifference” Elie Wiesel uses anaphora to emphasize the meaning and effect of indifference.

Indifference elicits no response. Indifference is not a response. Indifference is not a beginning; it is an end.

Anaphora in Literature and Film

Charles Dickens opens his novel A Tale of Two Cities with anaphora:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

Red’s famous advice to Andy in Stephen King’s Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption includes anaphora:

Get busy living, or get busy dying.

Through an anaphor-filled monolog, Will Hunting’s therapist Sean, in the film Good Will Hunting, shows Will that he (Will) doesn’t actually have all the answers. Here’s an excerpt:

So if I asked you about art you’d probably give me the skinny on every art book ever written… But I bet you can’t tell me what it smells like in the Sistine Chapel…

If I asked you about women you’d probably give me a syllabus of your personal favorites… But you can’t tell me what it feels like to wake up next to a woman and feel truly happy…

I ask you about war, and you’d probably, uh, throw Shakespeare at me, right?... But you’ve never been near one. You’ve never held your best friend’s head in your lap and watched him gasp his last breath, looking to you for help…

Anaphora in Lyrics

In the 1930s, George and Ira Gershwin created the timeless I Got Rhythm with the help of anaphora:

I got rhythm, I got music

I got my gal, who can ask for anything more?

I got daisies in green pastures

I got a wicked girl, who could ask for anything more?

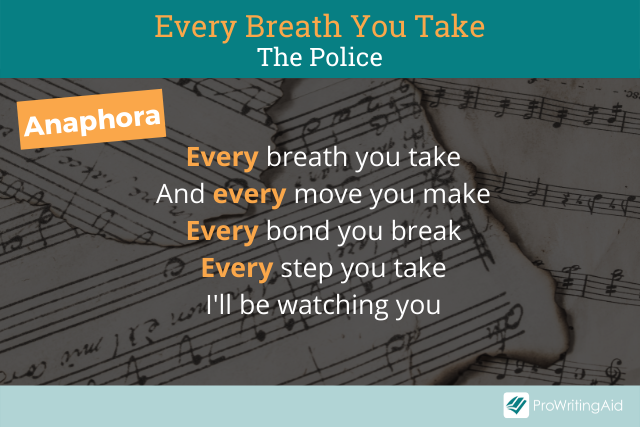

In the 1980s, The Police used anaphora to creepy effect in the hit Every Breath You Take. Anaphora lets the listener know they are always being watched.

Every breath you take

And every move you make

Every bond you break

Every step you take

I'll be watching you

In 2002, the speaker in Destiny’s Child’s Survivor proved their ex wrong with assistance from anaphora.

You thought that I’d be weak without you, but I’m stronger

You thought that I'’ be broke without you, but I’m richer

You thought that I’d be sad without you, I laugh harder

In 2014 Taylor Swift used anaphora to demand answers and emphasize her sense of betrayal.

Did you have to do this?

I was thinking that you could be trusted

Did you have to ruin

What was shining? Now it’s all rusted

Did you have to hit me

Where I’m weak? Baby, I couldn’t breathe

Anaphora in a Sentence

Literary devices find their way into everyday sentences, this includes anaphora.

Some people use them in daily affirmations: I am strong; I am capable; I am worthy.

They appear in common sayings:

- Go big or go home!

- Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.

Other times, we use them when we want people to understand exactly how we feel!

- I said it! I mean it! I expect you to do it!

- I love everything about you. I love your face. I love your mind. I love your heart.

- Don’t tell me what to do! Don’t tell me what to say! Don’t put me on display! (“You Don’t Own Me,” 1963)

- We demand to be heard. We demand action. We demand Justice.

What Is Anaphora in Poetry?

Anaphora is the same in poetry as it is in other forms of literature, speech, and writing: the repetition of words at the beginning of consecutive phrases, clauses, or lines.

Its rhythmic, sonic effects make it an especially fitting literary device for poets.

Examples of Anaphora in Poetry

Gwendolyn Brooks uses anaphora by repeating the single word “we” in We Real Cool, emphasizing the speakers’ steady movement toward a tragic end.

As Amanda Gorman’s inaugural poem The Hill We Climb nears its end, the poet repeats “we will” to inspire unity and hope among all regions of the nation.

In the final stanza of Poe’s The Raven, anaphora emphasizes the speaker’s overwhelming oppression which is caused by the raven.

Anaphora Is Powerful Rhetorical Device

Anaphora adds emotion and emphasis to your words. Anaphora creates rhythm in your words. Anaphora intensifies the impact of your words, making them resonant and more memorable.

You’ve witnessed the effect of anaphora in famous examples from literature, political speeches, social speeches, song lyrics, poetry, and everyday life.

How can you use it? Anaphora serves all writers and speakers and composers, not just the already-famous ones.