Fiction writers use Freytag’s Pyramid to ensure their stories have a clear dramatic structure and leave the readers completely satisfied.

Even if you haven’t heard of Freytag, I suspect you know more about him than you realize.

If you’ve watched a movie, TV show or series, or have read a novel or short story, you’ve probably seen his dramatic structure pyramid in action.

Freytag’s Pyramid is a staple of reading, literature, and creative writing classes. If you’re a fiction writer or reader, familiarity with this story structure device is worth your time.

Need a refresher? You’re in the right place!

What Is Freytag’s Pyramid?

Freytag’s Pyramid is a map that highlights dramatic structure—the order of events in which the plot of a story unfolds.

This concept was developed by Gustav Freytag, who was a German novelist, critic, and lecturer in the 19th century.

Though he was one of Germany’s most famous writers during his lifetime, Freytag is best remembered for his Pyramid.

He built his concept around the core elements of Aristotle’s theory. Known as Aristotle’s Poetics, this theory states that a story must have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Definition of Freytag’s Pyramid

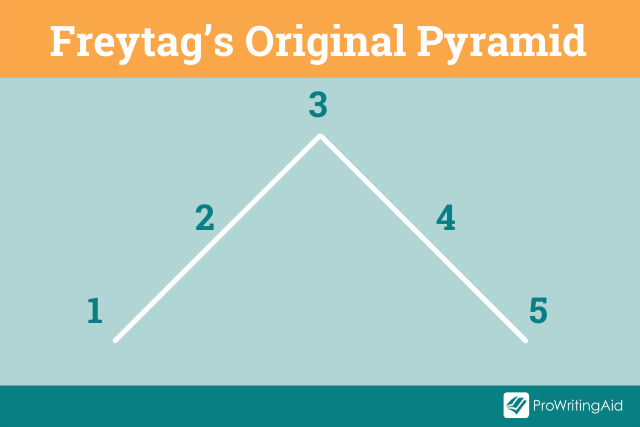

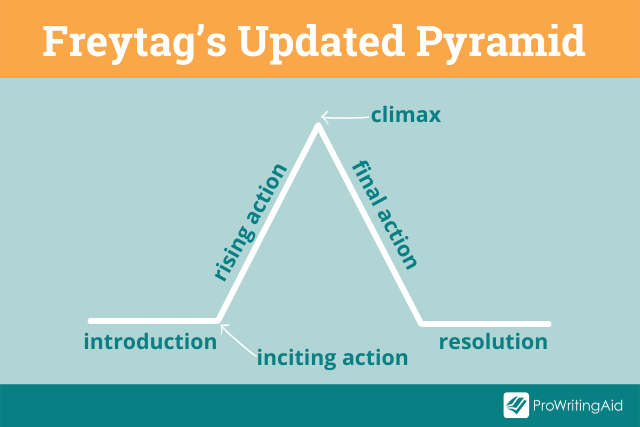

The definition of Freytag’s Pyramid is a five part dramatic structure that goes from the introduction into the rise, to the climax, falling action, and finally the resolution.

The action in a story rises and falls in the shape of a pyramid.

Freytag’s Pyramid Explained in Five Parts (with Examples)

In Freytag’s Technique of the Drama, Freytag divides plot into five parts:

- Introduction

- Rise

- Climax

- Fall

- Catastrophe

The entire plot is driven by a conflict—the protagonist is on a quest to achieve something.

Conflict is what stands between a character and their goals. The plot elements represent the different stages of that conflict.

This story structure works as a three-act structure or a five-act structure.

As a three-act structure, the introduction with the exciting force typically make up Act One. Act Two is the rising action and climax. Falling action and catastrophe or resolution make up Act Three.

Element 1: Introduction

The introduction is where the characters and the setting are first presented to us.

Additionally, the author will include some background or “backstory” information on those characters, including their relationship and situations.

Consider Cinderella, the Disney version. I’m willing to bet that you know the general storyline.

In the introduction, we learn that Cinderella is a kind young woman who lives with her wicked stepmother and stepsisters.

She is forced to live alone in their tower and complete their undesirable household chores.

Her loving father has died and the only friends she has are the mice and birds who talk to her when none of the wicked family members are around.

Then, a key event (the exciting force) happens at the end of that introduction.

The event propels the story into action. It marks a change and the start of the journey, and conflict, for the protagonist. Do you remember what the event is in Cinderella?

The invitation to the ball, of course! Now Cinderella begins her quest to attend the ball (dressed appropriately, of course).

Element 2: Rise

The rise is where “the plot thickens.” This is the phase in which the protagonist moves forward in their journey, possibly facing setbacks and complications.

It’s where the tension builds, the suspense sharpens, characters develop, and we—the readers—sit on the edge of our seats to see whether that protagonist will succeed!

Weren’t you a nervous wreck during Cinderella? All Cinderella’s attempts to pull together a dress; all the messes made by the step-family to distract her; all the singing!

Then, the worst setback, the destruction of the dress!

With the plot still on the rise, Cinderella’s fairy godmother appears and magically makes everything perfect. But, there’s one hitch in the plan: the magic will wear off at midnight.

The plot is still rising and will go through dances, more singing, a perfect night, and the clock striking midnight. Then the glass slipper falls off and the prince runs after Cinderella only to find a single shoe.

Finally Cinderella is back in the tower, cleaning and singing away her sorrow, and dreaming of the magical ball with the prince.

Will Cinderella ever get to be with the one guaranteed to be her true love (all that singing and dancing proves it’s love, right)?

The prince is searching for the shoe-owner, but how will he ever find Cinderella while she’s stuck in the tower?

The climax answers these questions.

Element 3: Climax

The climax is where the turn—for better or worse—comes for the protagonist. It is the moment that largely determines how the story will end.

For Cinderella, that turn comes when she goes downstairs so the Grand Duke can see if the solitary glass slipper fits.

After dodging yet another complication (the stepmother trips the Duke and he drops and breaks the shoe... but Cinderella has the match!), Cinderella proves she is the girl of the prince’s dreams!

Element 4: Fall

This is where the fallout happens—that little wordplay can help you remember what the fall is. The results of the climax occur here.

Note that Freytag built his pyramid for the genres of realistic drama or tragedy. So for him, the fall would usually show a continued unraveling of the protagonist’s journey or quest.

While you may not think of Cinderella as a comedy, it is a story with a happy ending. It also has a really short fall.

Cinderella goes right from that shoe-fitting to her wedding.

We can imagine the unraveling of her wicked family’s household and her joy as she prepares for her wedding, but we don’t actually see those events.

Element 5: Catastrophe

This point in the plot is where the final failure occurs. Remember, Freytag was tragedy-focused. The protagonist’s journey ends with a final devastation.

Think of Shakespeare’s tragedies: Hamlet, and just about everyone else, is dead; Romeo, Juliet, and some of their friends are dead; Othello kills himself.

There’s lots of death, and then those stories end.

But Cinderella has a happy ending, so what do we call her “happily ever after” ending?

Remember when I said there have been adjustments to Freytag’s Pyramid over time? One of those adjustments was to that catastrophic ending.

6 Stages of Plot in Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag had five elements of plot, but many writers think that’s an oversimplification.

If you’ve discussed dramatic structure in school or writing classes, you’ve probably been instructed in six (or perhaps seven: some people separate the resolution and denoument).

This story structure approach includes these elements:

- Introduction, also called the Exposition.

- Inciting Incident or Inciting Action: this is included in Freytag’s Pyramid as part of the introduction called the Exciting Force. In updated models, this event gets its own spot on the pyramid.

- Rising Action, serves the same function as Freytag’s Rise.

- Climax, also called the Turning Point, is the moment the reader/audience has been waiting for! It’s the highest point of the action, where all the major conflict comes together.

- Falling Action, serves a similar function to Freytag’s Fall, but includes space for non-tragic fallout.

- Resolution, also called the Denouement. Some writers and scholars see these elements as separate parts, with the Denouement almost serving as an Epilogue. In the Resolution, the protagonist’s conflict is resolved, for better or for worse.

For Cinderella, her quest to be in the prince’s presence was resolved more positively than she had imagined. Her struggle to attend the ball led to her fairy-tale wedding.

The Differences

The fundamental differences between Freytag’s model and the six (or seven) point model are seen in the Climax, Catastrophe, and Resolution segments.

Climax

For Freytag, the Climax represented the turning point rather than “the moment we’ve all been waiting for.”

In fact, he might disagree with my interpretation of Cinderella’s climax and say it occurred at midnight, when Cinderella lost her slipper. That’s the event that “turns” the rest of the story.

Catastrophe

Freytag’s focus was on tragedy. In his model, there would be a final catastrophic event (brought on by the climax) that determined the end for the protagonist.

For example, in Othello, Freytag would likely see the murder of Desdemona as the climax, and Othello’s suicide as the catastrophe.

Let’s apply the catastrophe to Cinderella, with a twist. If the lost shoe was the climax, the shoe-fitting moment would be the “happy” catastrophe.

Resolution

In Freytag’s Pyramid, the catastrophe is the devastating end of the protagonist’s conflict.

In the six-point model, the protagonist’s conflict ends or is resolved in the resolution, happily or unhappily.

How to Use Freytag’s Pyramid

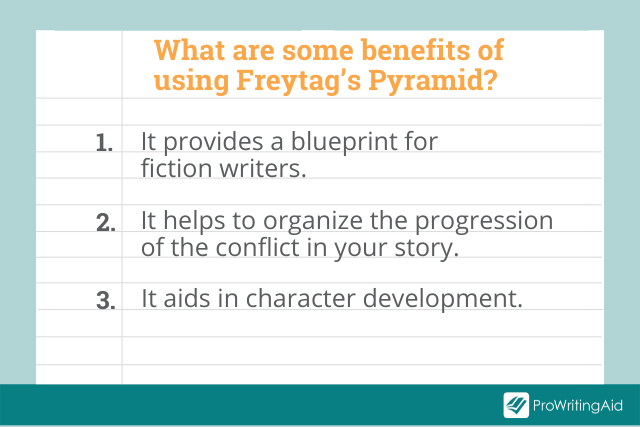

Freytag’s Pyramid provides the structure of a builder’s blueprints (somewhat) or a chef’s recipe (a better match, I’ll explain soon) to the fiction writer.

The dramatic structure serves as an outline for your story, helping you organize the progression of the conflict and character development.

A story without a sense of structure is like a dream—it doesn’t really make sense and it’s almost impossible to understand why any of the events are occurring.

Because Freytag’s Pyramid is such a ubiquitous dramatic structure, readers are ready for it, even if they don’t consciously realize it.

Freytag’s format of plot progression is one that readers (or viewers) engage with naturally.

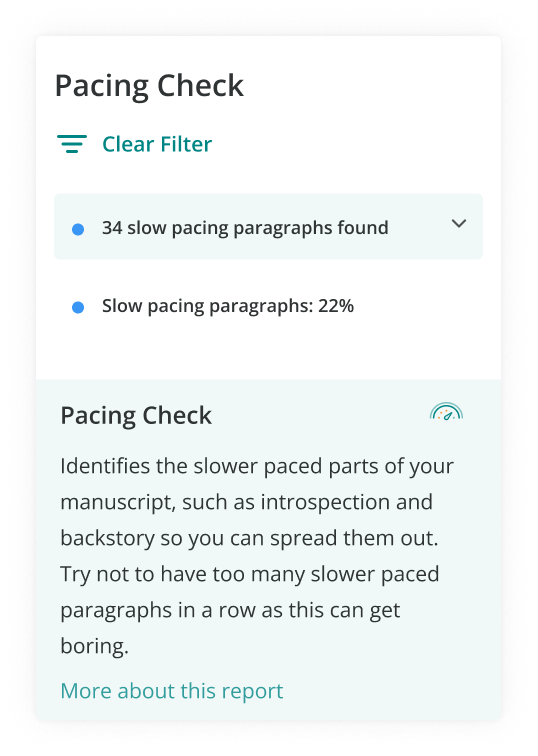

Freytag’s pyramid is also helpful in pacing your story as a whole. If you need help with pacing on a scene or chapter level, you can use ProWritingAid’s Pacing Report.

This will help you identify words or phrases that speed up or slow down your writing.

Using Freytag’s Pyramid to Fit Your Own Writing

Treat Freytag’s Pyramid as the chef treats the recipe more than as the builder treats the blueprint. It’s best used as a guide, not a formula.

Builders have to stick to that blueprint. Danger awaits if they don’t! Chefs have more leeway, and so do writers.

Length

Not every introduction, rising action, climactic scene/s falling action, or resolution has to be a certain length.

As a writer, you have to determine how to develop each of these plot points to best serve your story.

Similarly, each plot element does not have to match in length. Your introduction might be significantly longer than the resolution. Again, you have to determine what your story needs.

Order

You’ve probably seen films that start in medias res (like Forrest Gump or Goodfellas) or that start with the ending (like The Usual Suspects or The Hangover).

You’ve likely read books that open the same ways (Daphne DuMaurier’s Rebecca is one example of a book that begins with an ending ). That manipulation is allowed! The pyramid should guide you, not confine you.

Though these films (and books) shake up the pyramid, they still demonstrate the overarching chronology and progression the pyramid provides, ultimately taking us back to the start of the story, and leading us through the rise, fall, and resolution.

What Are Some Other Dramatic Structures?

Not everyone loves Freytag’s Pyramid. Modern writers sometimes find it formulaic or overused, and instead implement complicated time-hops or out-of-sequence events.

Modern writers also use The Hero’s Journey and Dan Harmon’s Story Circle, among other structures.

Options are good, and you should explore them all to see what structure suits your story best.

Still, it’s smart to have Freytag’s Pyramid at your fingertips. The structure gives definitive shape to your work, providing a flexible and familiar framework to help you flesh out ideas.

If you’re looking for a place to delve into the various dramatic structures, then ProWritingAid’s Writer’s Community is the place to be.

From Freytag’s Pyramid to the Hero’s Journey and everything in between, join a forum of aspiring and established writers to discover what structures work best for you.

Example of How to Use Freytag’s Pyramid

Check out 2019’s short-film Oscar winner: Matthew E. Cherry’s Hair Love. As you watch, see if you recognize the different elements of Freytag’s Pyramid, the updated six (or seven) point version.

If you don’t want my input until after you’ve watched, stop reading now! Then, come back and compare. Enjoy the film!

Introduction: We’re introduced to the little girl, her family (through the photo), and learn that “today” is a special day that’s marked with a heart on her calendar. We also learn that she’s got quite a lot of hair.

Inciting Event: The little girl (we later learn her name is Zuri) finds a hairstyle she wants to recreate with her own hair.

Rising Action: Zuri tries to style her hair, but isn’t successful. Her dad tries to put a hat on her hair, intimidated by the task of styling it, but Zuri refuses it; she wants to look her best.

We see what the two go through to try to style Zuri’s hair, only to see them fail again, leaving Zuri in tears and the dad defeated.

Then, he hears/sees the vlog with Zuri’s mom giving the hairstyle tutorial, and dad and daughter try again.

Climax: They do it! Zuri’s hair is perfect!

Falling Action: We see Zuri’s mom in the hospital, without hair, somewhat self-conscious. The family reunites, and the mom shows she’s impressed with Zuri’s hair.

Zuri then gives her mom the picture she made of her with a crown, encouraging her to be proud of her appearance, too.

Resolution: The family leaves the hospital together—they not only “won” the hair conflict, but are all together again.

Denouement: If you watched the credits, the ending gets happier as Zuri’s mom’s hair regrows showing she has defeated the illness that caused her hair loss.

Understanding Freytag’s Pyramid is basic knowledge for any sort of storyteller. As a writer, it can help you understand the basics of plot structure.

Once you know the rules, you can bend and break them to craft your own story.

[This article was updated by Krystal N. Craiker]