What do Shanghai in 1926, New York City in the mid-1950s, and an interplanetary spaceship in 2067 have in common?

They’re all settings for popular retellings of Romeo and Juliet—Chloe Gong’s These Violent Delights, Broadway’s West Side Story, and Lauren James’ The Loneliest Girl in the Universe, respectively.

Retellings are a classic art form, and they’re a popular trend in the fiction industry right now. Writing a retelling is an easy way for emerging authors to gain traction.

Readers know the classic stories they like and will gravitate toward a story with a pitch, like Jane Eyre set on a modern university campus, or Cinderella told from the ugly stepsister’s perspective, even if they’ve never heard of the author.

If there are any classic stories that you know and love, a retelling can be a fun option to consider for your next project.

Read on to learn how to write a unique retelling that will make readers see an old story in a new light.

- What Kinds of Stories Are Good for Retellings?

- How Do I Retell an Old Story in a New Way?

- How Do You Rewrite a Story with a Different Main Character?

- How Do You Change the Setting when Retelling a Story?

- How Do You Rewrite a Story in a Different Genre?

- How Do You Stay True to Yourself when Writing a Retelling?

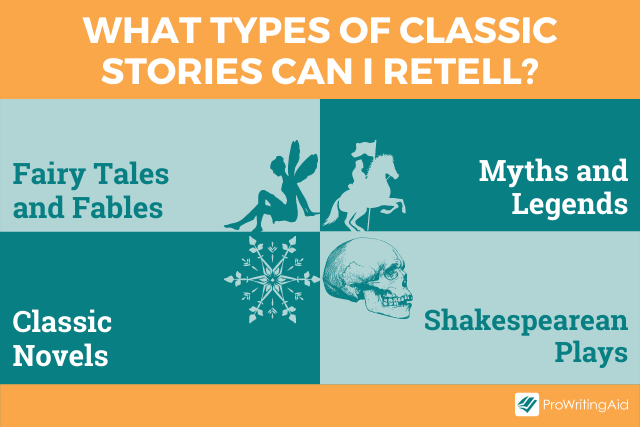

What Kinds of Stories Are Good for Retellings?

There are countless popular tales from cultures around the world that would make fantastic fodder for a retelling.

Decide what kind of story you’re interested in writing—a funny story, a tragic story, a heart-warming story, or something else entirely. Then, find a classic story that fits the style you gravitate toward.

Here are four categories of classic stories to consider.

1. Fairy Tales and Fables

Fairy tales and fables lend themselves especially well to retellings, perhaps because so many versions of each story already exist. Most of these tales were passed down through word of mouth, instead of stemming from a single source, so they naturally evolved over time.

It might feel daunting to join such a crowded space, but no one else has the same perspective you do. Trust that you have something new to bring to the table.

Examples to consider:

- Works by Hans Christian Andersen (e.g. The Emperor’s New Clothes, The Little Mermaid, The Snow Queen)

- Works by the Brothers Grimm (e.g. Hansel and Gretel, Rumpelstiltskin, The Pied Piper of Hamelin)

- Fairy tales from cultures around the world (e.g. Bunbuku Chagama, Baba Yaga, The Jackal’s Eldest Son)

2. Myths and Legends

Myths and legends are another fantastic option. Many of these stories are beautiful and continue to resonate with people today.

If you use a myth from a culture other than your own, take a step back to consider whether you’re the right writer for this retelling. You always want to pay homage to your source material, rather than take advantage of it.

Examples to consider:

- Greek mythology (e.g. the Fates, Prometheus, Persephone and Hades)

- Norse mythology (e.g. Thor and Loki, Sif and her Golden Hair, Fenris the Wolf)

- Egyptian mythology (e.g. the Story of Re, the Isis and Osiris, the Underworld and Anubis)

3. Shakespearean Plays

Shakespeare’s work is in a league of its own for classic stories that we use as a cultural touchstone.

You can decide how closely you want to stick with the source material. Some retellings use Shakespeare’s verses word-for-word, while others only quote a few key lines or loosely retain the original plot.

Examples to consider:

- Shakespearean tragedies (e.g. Hamlet, Julius Caesar, Macbeth)

- Shakespearean comedies (e.g. As You Like It, The Merchant of Venice, A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

4. Classic Novels

Last but not least, you can always build on the work of other novelists.

If you choose this option, it’s more likely that there will be a single source for you to draw from, instead of needing to research countless existing versions and retellings. This is a trade-off: it makes your research simpler, but it also gives you fewer options for new directions in which to take the story.

Examples to consider:

- Jane Austen’s work (e.g., Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Emma)

- Charles Dickens’ work (e.g., Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol, Great Expectations)

- Leo Tolstoy’s work (e.g., Anna Karenina, War and Peace, The Death of Ivan Ilyich)

Regardless of which category you decide to draw from, the most important thing is to choose a story that speaks to you.

You’ll need to spend a lot of time with the source material—and with existing retellings—to do the story justice. Choosing the right story will make the writing process much more rewarding.

How Do I Retell an Old Story in a New Way?

Once you’ve gotten to know your source material well, it’s time to find a unique angle for your version of the story.

The key to writing a retelling is to change one or more of the most crucial elements of the original story. Most retellings rely primarily on one of these three strategies:

- A new protagonist

- A new setting

- A new genre

Let’s examine each of these three elements and discuss how to get started with each strategy.

How Do You Rewrite a Story with a Different Main Character?

The first strategy is to tell the story through the eyes of a character who isn’t the usual protagonist.

Take the fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood, for example. It’s traditionally told through the perspective of Little Red Riding Hood herself, but you could tell the same story from the perspective of the grandmother, the huntsman, or the wolf.

Or you could even go a step further and enter through the perspective of a character who isn’t in the original story, such as Little Red Riding Hood’s best friend in the village, or Little Red Riding Hood’s future granddaughter.

Each new lens drastically changes the meaning of the story and its emotional heft.

This type of retelling reminds readers to keep an open mind. Every character feels like the protagonist of his or her own life, and retellings with new protagonists show us that there can be many sides to the same story.

Examples of retellings with a new protagonist:

- Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire: a retelling of L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz from the perspective of the Wicked Witch

- A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes: a retelling of the Trojan War from the women’s point of view

- The Chosen and the Beautiful by Nghi Vo: a retelling of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby from Jordan Baker’s perspective

If you want to write a retelling with a new protagonist, you should start with these steps:

Step 1. Make a list of the major characters in the original story, including the antagonist and major side characters.

Step 2. Identify the characters on your list who might have an interesting and unique point of view. Ask yourself:

- Which of these characters do you feel curious about?

- Which of these characters is the most hated / misunderstood?

- Which of these characters could have the most interesting growth / character transformation through the course of this story?

Step 3. Sketch out a potential story arc from your chosen character’s perspective. Ask yourself:

- What does this character want at the beginning of the story? How do they try to get it?

- What obstacles does this character face throughout the story? How do they try to defeat those obstacles?

- How does the story end for this character? Have they changed by the end of the story?

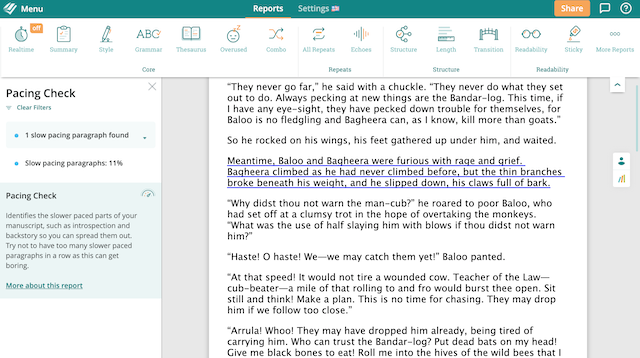

ProWritingAid’s Pacing Report can help you write an interesting character arc. It identifies slower paced parts of your manuscript so that you can effectively balance introspection with action.

Sign up for a free ProWritingAid account to try the Pacing Report.

How Do You Change the Setting when Retelling a Story?

Another strategy is to change the setting of the story. You preserve the backbone of the original story, but set it a different time period and place.

One common way to do this is by modernizing an older story by setting it in a modern-day workplace, school, or neighborhood. Many authors use this strategy to make classic stories accessible to readers.

Another way to do this is to transplant a story to the context of a different country or culture. For example, you could tell the story of Snow White set in medieval India instead of in medieval Europe.

This type of retelling can be a powerful reminder that many stories have timeless or universal themes. Two people falling in love in the 15th century might have experienced the same emotions as two people falling in love today.

Examples of retellings that change the setting:

- The Broadway musical West Side Story: a retelling of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Julie set in the Lower West Side of Manhattan in the mid-1950s

- The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach: a retelling of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick about a modern-day baseball player in Michigan

- Anna K by Jenny Lee: a retelling of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina about a modern-day Korean-American girl in Manhattan high society

If you want to change the setting, you should start with these steps:

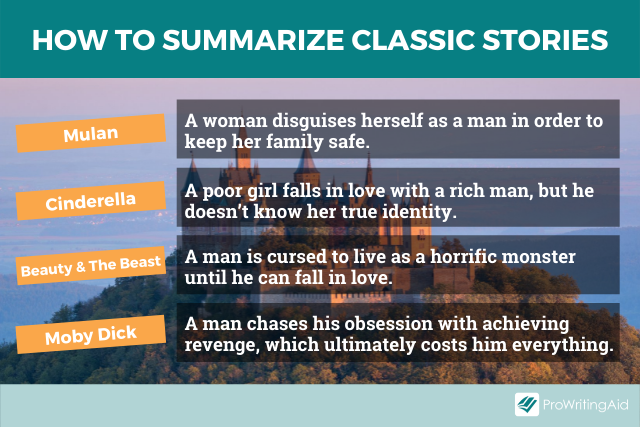

Step 1. Summarize the core premise of the original story in a single sentence, without mentioning the setting. For example, you might summarize Mulan this way: “A woman disguises herself as a man in order to keep her family safe.”

Step 2. Brainstorm a variety of potential settings you find compelling. Try to choose ones that are drastically different from the original setting of the story. If you’re out of ideas, here are some settings to start with:

- A modern high school in the American suburbs

- A speakeasy in the roaring 20s

- A bookstore in Paris during WWII

- A technology company in Silicon Valley

- A mining site in the 1850s Gold Rush

Step 3. Pick your favorite setting from Step 2 and combine it with the summary you wrote in Step 1. For example: “A woman disguises herself as a man in order to keep her family safe—at a technology company in Silicon Valley.” Ask yourself:

- How would this setting affect the protagonist and the other main characters? (e.g. new careers, new socioeconomic backgrounds, new goals)

- How would this setting affect the major conflict of the story? (e.g. a duel to the death in a medieval setting might become a corporate war in a modern setting)

- How would this setting affect the themes of the original story? Which themes would be preserved and which themes would no longer feel relevant?

Download our free guide to world-building

How Do You Rewrite a Story in a Different Genre?

The last strategy is to tell the same story with a different genre.

If you’re retelling a literary story, you can choose to introduce some element of the fantastical. You could make it a fantasy story by making the protagonist a wizard or a werewolf, for example, or you could make it a sci-fi story by making the core conflict dependent on time travel or human cloning.

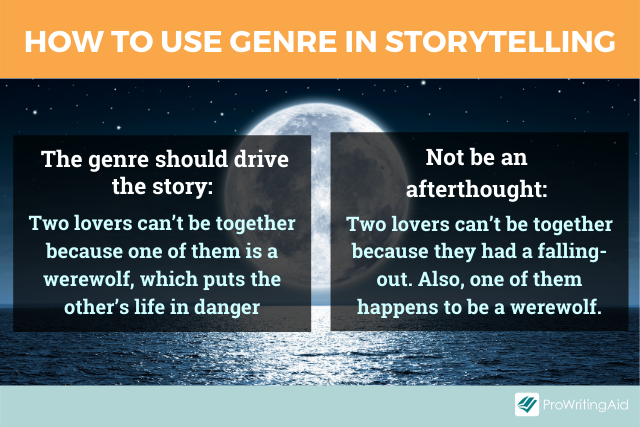

The most important thing to remember is that the genre should be part of the fundamental skeleton of the story itself, not just an afterthought. When you change the genre, some element of the new genre needs to drive the narrative arc.

Examples of retellings that change the genre:

- Cinder by Marissa Meyer: a sci-fi retelling of Cinderella in which Cinderella is treated as a second-class citizen because she’s a cyborg, not a human

- Snow, Glass, Apples by Neil Gaiman: a fantasy retelling of Snow White in which Snow White has skin as white as snow and lips as red as blood because she’s actually a vampire

- Pride and Prejudice and Zombies by Seth Grahame-Smith: a horror/comedy retelling of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice in which Elizabeth’s attempts at love are repeatedly almost thwarted by a zombie apocalypse

If you want to write a retelling with a new genre, you can start with these three steps:

Step 1. Choose your new genre and, better yet, your sub-genre. If you normally write in one genre, you may already know what you want to write. Otherwise, here are some options to consider:

- Fantasy (subgenres: sword and sorcery, paranormal, portal fantasy, etc.)

- Sci-fi (subgenres: space opera, post-apocalyptic, cyberpunk, etc.)

- Horror (subgenres: Gothic, zombies, gore, etc.)

Step 2. Choose a specific element of your new genre—such as mythical creatures, portals to other worlds, or an alien invasion—that would cast the story in a whole new light. How will the core conflict of the story be driven by this specific element?

Step 3. Research the common tropes of the genre you’ve chosen and make a list of the ones you like. Could you introduce any of these tropes into your retelling? How would they affect the original story?

How Do You Stay True to Yourself when Writing a Retelling?

Ultimately, the most important thing is to tell a story that feels authentic to you.

Think about your own life and the experiences that have shaped you most. How can you use those to inform the story you want to tell? What’s unique about the way you see the world?

If you’re part of a historically marginalized group, you can make the story your own simply by bringing in a new point of view. Many traditional stories lack the diversity and inclusivity of our society today, so bringing in your point of view makes it possible for modern readers to see themselves reflected in the stories that they love.

Don’t be afraid to take risks and try new things.

All artists steal. The key is to know how to steal in a way that honors and acknowledges the original work while building something new.

If you’re ever worried about plagiarism, you can use ProWritingAid’s plagiarism checker to check how much of your draft is original.

As long as you treat the original story with respect, the only limit is your own creativity.

These are the most common strategies to write a retelling, as well as some of our favorite examples.

What are your favorite retellings? Let us know in the comments below.