The words which, where, and who are relative pronouns, which means they introduce a clause that modifies part of the main sentence.

Including a comma before a relative pronoun will change the meaning of the sentence.

It can be tricky to remember when you need to use a comma before a relative pronoun and when you don’t. So when should you use a comma after which, where, and who?

The short answer is that it depends on the importance of the information that is attached to the relative pronoun.

In general, if the information that follows the relative pronoun is essential to the sentence, you should not use a comma. But if the information is extra and the sentence can stand alone without it, you should use a comma.

This article will explain this rule in detail and give you examples of sentences that should and should not use a comma before which, where, and who.

We’re about to get into a lot of rules and while you can always bookmark this article for easy reference, we’re going to put you on to a cheat code: ProWritingAid’s Grammar Checker. You’ll never have another missing or misplaced comma with its powerful Realtime Checker.

Sign up for a free account and try it today.

Do You Put a Comma Before Which? When to Do It

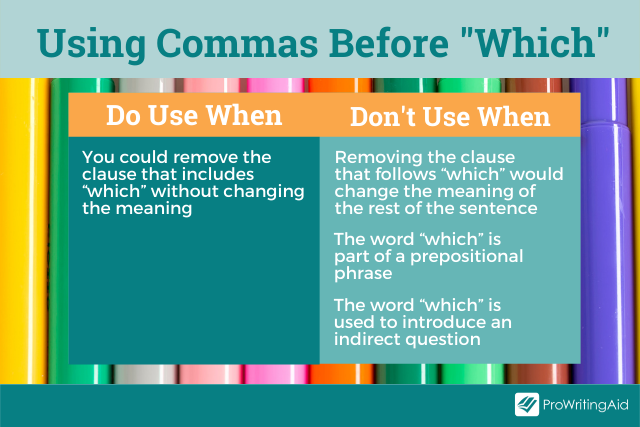

You should use a comma before “which” if:

- You could remove the clause that includes “which” without changing the meaning of the main sentence

You don’t need to use a comma before “which” if:

- Removing the clause that follows “which” would change the meaning of the rest of the sentence

- The word “which” is part of a prepositional phrase like “in which,” “from which,” or “with which”

- The word “which” is used to introduce an indirect question

Examples of Using a Comma Before Which

- Example 1: “The peregrine falcon, which can dive at speeds of almost 200 miles an hour, is the fastest bird in the world.”

In this example, the main sentence is “The peregrine falcon is the fastest bird in the world,” and the information attached to the relative pronoun is “which can dive at speeds of almost 200 miles an hour.”

This sentence can stand alone without the clause that includes the relative pronoun, so we do use a comma before the word “which.”

- Example 2: “I have a few thousand dollars saved up right now, which should be enough to fund my summer abroad.”

Here, the main sentence is “I have a few thousand dollars saved up right now”, and the information attached to the relative pronoun is “which should be enough to fund my summer abroad.”

Again, this sentence can stand alone without that extra information, so we do use a comma before the word “which.”

- Example 3: “My dad’s old violin, which he got back in the 90s, is the most expensive instrument I’ve ever played.”

See if you can identify the main sentence in this final example. Can it stand alone without the information attached to the word “which”?

Examples of When NOT to Use a Comma Before Which

- Example 1: “This is the prison cell in which a famous monarch spent the last days before her execution.”

The word “which” is part of the prepositional phrase “in which.” You never need to use a comma before “which” if it’s part of a prepositional phrase.

- Example 2: “I don’t know which way to go.”

In this example, the word “which” introduces a question (the indirect form of “Which way should I go?”), so you shouldn’t use a comma before it.

- Example 3: “I asked my mom which dress I should wear to prom, and she said they all looked beautiful.”

Again, the word “which” introduces a question (the indirect form of “Which dress should I wear to prom?”), so you shouldn’t use a comma before it.

When to Use a Comma After Which

The only time you need to use a comma after “which” is when you’re including an aside or a parenthetical phrase between the word “which” and the information that comes after it.

For example, you might say: “This chapter will be included in our final exam, which, in case you weren’t paying attention, is taking place next Tuesday.” In this case, the phrase “in case you weren’t paying attention” is a parenthetical phrase, so you would use a comma to separate it from the rest of the sentence.

Should You Put a Comma Before Where?

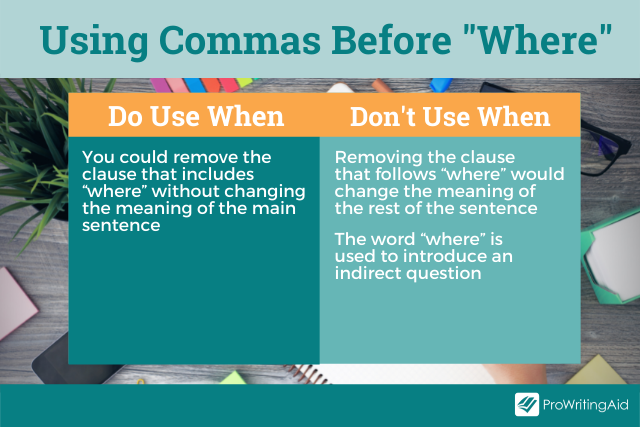

You should use a comma before “where” if:

- You could remove the clause that includes “where” without changing the meaning of the main sentence

You don’t need to use a comma before “where” if:

- Removing the clause that follows “where” would change the meaning of the rest of the sentence

- The word “where” is used to introduce an indirect question

Examples of Using a Comma Before Where

- Example 1: “The city of Yakutsk, where temperatures average minus 50 °C, is considered the coldest city on Earth.”

The main sentence is “The city of Yakutsk is considered the coldest city on Earth,” and the information attached to the relative pronoun is “where temperatures average minus 50 °C.” This sentence can stand alone without the information that follows the relative pronoun, so we do use a comma before the word “where.”

- Example 2: “I’m headed to Boston, where my brother is waiting for me.”

Here, the main sentence is “I’m headed to Boston,” and the extra information is “where my brother is waiting for me.” Again, this sentence can stand alone without that extra information, so we do use a comma before the word “where.”

- Example 3: “I went to college in a wealthy part of Connecticut, where practically everyone spoke with a posh accent.”

See if you can identify the main sentence in this final example. Can it stand alone without the information attached to the word “where”?

Examples of When NOT to Use a Comma Before Where

- Example 1: “Seattle was the first city where I lived on my own after I graduated college.”

In this example, the phrase attached to the word “where” is “I lived on my own after I graduated college.” Without this phrase, the sentence is simply “Seattle was the first city.” This sentence means something different from what it was intended to mean. Therefore, you shouldn’t use a comma before the where, because you can’t split the two phrases apart.

- Example 2: “Do you know where I left my keys?”

In this case, the word “where” introduces a question (the indirect form of “Where did I leave my keys?”), so you don’t need a comma before it.

- Example 3: “I asked my mom where I can park my car tonight.”

Again, the word “where” introduces a question (the indirect form of “Where can I park my car tonight?”), so you don’t need a comma before it.

When to Use a Comma After Where

The only time you need to use a comma after “where” is when you’re including an aside or a parenthetical phrase between the word “where” and the information that comes after it.

For example, you might say: “We’re standing in front of Oxford University, where, for the movie buffs in the crowd, many of the scenes in the Harry Potter franchise were filmed.” In this case, the phrase “for the movie buffs in the crowd” is a parenthetical phrase, so you would use a comma to separate it from the rest of the sentence.

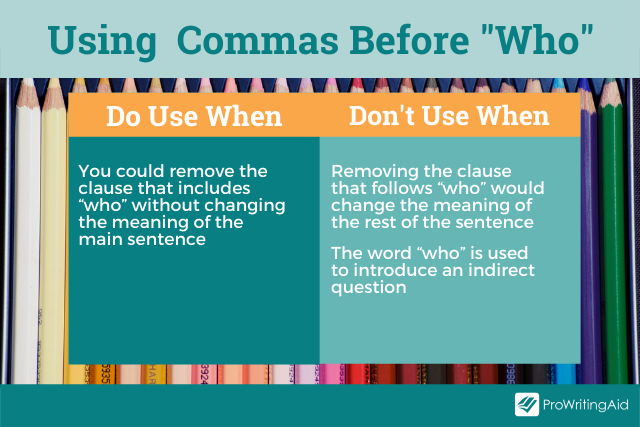

When to Use a Comma Before Who

You should use a comma before “who” if:

- You could remove the clause that includes “who” without changing the meaning of the main sentence

You don’t need to use a comma before “who” if:

- Removing the clause that follows “who” would change the meaning of the rest of the sentence

- The word “who” is used to introduce an indirect question

Examples of Using a Comma Before Who

- Example 1: “My colleague Jeremy, who you met at the Christmas party last year, just signed up for a membership at your gym.”

In this example, the main sentence is “My colleague Jeremy just signed up for a membership at your gym,” and the clause attached to the word “who” is “you met at the Christmas party last year.” Because the sentence can stand on its own without this extra information, we do use a comma before the word “who.”

- Example 2: “My landlord has a bulldog named Francis, who growls at me every time I enter the building.”

Here, the main sentence is “My landlord has a bulldog named Francis,” and the phrase attached to the word “who” is “who growls at me every time I enter the building.” Again, we need a comma because the sentence can stand alone without the extra clause.

- Example 3: “Barack Obama, who was born in Honolulu, became the first African-American president of the United States in 2009.”

See if you can identify the main sentence. Can it stand alone without the information attached to the word “who”?

Examples of When NOT to Use a Comma Before Who

- Example 1: “All I want is to date a man who loves reading books just as much as I do.”

In this example, the phrase attached to the word “who” is “who loves reading books just as much as I do.” Without this phrase, the sentence is “All I want is to date a man.” This sentence means something different from what it was intended to mean. Therefore, you shouldn’t use a comma before “who,” because you can’t split the two phrases apart.

- Example 2: “I hate having to work with people who don’t pull their own weight on the team.”

Here, the phrase attached to the word “who” is “who don’t pull their own weight on the team.” Without this phrase, the sentence is “I hate having to work with people.” This sentence means something different from what it was intended to mean. Again, we need a comma before the word “who.”

- Example 3: “I asked my mom who I should invite to my birthday party.”

In this case, the word “who” introduces a question (the indirect form of “Who should I invite to my birthday party?”), so you don’t need a comma before it.

When to Use a Comma After Who

The only time you need to use a comma after “who” is when you’re including an aside or a parenthetical phrase between the word “who” and the information that comes after it.

For example, you might say: “This is my Grandma Nancy, who, if I do say so myself, makes the best chocolate chip cookies in the country.” In this case, the phrase “if I do say so myself” is a parenthetical phrase, so you would use a comma to separate it from the rest of the sentence.

Conclusion on Using a Comma Before Which, Where, and Who

There you have it: a comprehensive guide for when to use a comma before the words which, where, and who.

Was this article helpful? Let us know in the comments.