Table of Contents

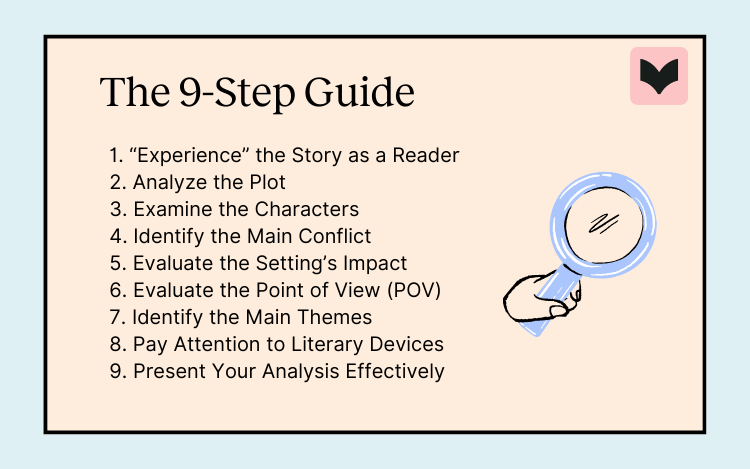

If you’re an aspiring editor or an author looking to sharpen your storytelling skills, learning how to analyze your own work (and that of others) can help you make meaningful edits and improvements.

Story analysis involves examining a narrative’s components to understand how well they work together. But don’t let this simple definition fool you—it’s both an art and a science that usually takes a long time to master.

Whether you’re looking to revise a novel or a shorter piece of fiction, this guide will show you how to analyze a story in nine steps. Let’s begin.

1. “Experience” the Story as a Reader

The first step is to read the story with fresh eyes as a regular reader would, allowing yourself to experience it naturally. This will give you a general impression of the narrative and help you spot initial strengths and weaknesses that will serve as a foundation for deeper analysis.

Even if the story isn’t flawlessly crafted, certain elements will likely stand out—maybe a quirky character, sharp dialogue, a vivid setting, or a satisfying arc. Take note of these, along with a brief summary of the plot.

Once you have a good grasp of the story’s premise, you can start breaking down its key elements for a more detailed evaluation.

2. Analyze the Plot

The plot is one of the first things you’ll need to analyze (though there’s no strict order to follow). As the backbone of the story, the plot holds everything together; without a solid one, even the most beautiful writing can fall flat.

To analyze it thoroughly, start by creating a scene-by-scene breakdown. Summarize each scene in a few words to track how they connect. The key question to ask yourself is: Does this scene move the narrative forward? If not, it either needs to be reworked or cut.

Beyond scene causality, also consider the overall structure. Does the story follow a recognizable framework, like the three-act structure, with a strong beginning, middle, and end? Not all works of fiction require it, but most fall into it.

Look for these key structural moments:

Exposition (0–10%): Introduces the setting, characters, and initial situation.

Inciting Incident (10–15%): The event that kick-starts the main conflict.

Rising Action (15–75%): The bulk of the story, where tension builds through obstacles, character development, and the rising of stakes.

Climax (75–90%): The story’s turning point and the peak of conflict.

Falling Action (90–95%): The aftermath of the climax, where loose ends start getting resolved.

Denouement (95–100%): The final resolution or conclusion, showing the new status quo.

If the timing of these moments feels off—say, if the inciting incident doesn’t occur until halfway through—then that can disrupt pacing and throw off the reader’s expectations.

After you’ve taken a good look at the plot, it’s time to focus on the stars of the show…

3. Examine the Characters

Characters are often the heart of a story. They are the portal through which readers experience the events, so they need to be compelling and engaging.

When analyzing characters, ask yourself:

Do they have clear motivations and goals that drive their actions?

Do they have a mix of strengths and flaws that make them relatable?

Do they share meaningful relationships with other characters in the story?

Of course, you’ve got to pay special attention to the protagonist, but you’ll also need to apply this same level of scrutiny to other key characters—such as the antagonist and supporting characters. Each of them should serve a clear purpose in the story, whether it’s creating obstacles for the hero or helping them achieve their goals.

And Their Development

Speaking of which, the protagonist's character arc is one of the most important elements to dissect. They should aim to achieve something (their external goal) but also believe in some lie or misconception that prevents them from getting what they want.

Through the trials and tribulations of the story, they should learn a necessary lesson before getting what they actually need (their internal resolution). For example, in The Hobbit, Bilbo learns that to be a hero, he doesn’t need to be a swordsman or a dragon killer—he just needs to act with courage, which he already possesses.

As you evaluate the protagonist’s character development, ensure they act consistently with their established traits while changing subtly and believably in response to their experiences, ultimately integrating these changes into a coherent new self by the story’s end.

Also, distinguish between static/flat characters who do not change and dynamic/round characters who evolve. Both can be effective when used purposefully—not every character needs a dramatic arc, but each should contribute meaningfully to the overall narrative.

💡 You can support your analysis using ProWritingAid’s Manuscript Analysis or Chapter Critique to get actionable feedback on your story’s plot, characters, setting, and other key elements.

4. Identify the Main Conflict

Without a meaningful conflict at the heart of the story, there’s no story at all. Conflict drives the narrative forward and keeps readers engaged from beginning to end. The most effective stories feature both external and internal conflicts that interact with and amplify each other throughout the narrative.

When analyzing conflict, first identify the nature of the main external challenge. Who or what is the protagonist struggling against? It might be:

another character (like an evil space lord)

a hostile environment (like a desert island)

an impersonal force (like a corrupt government system)

technology gone awry (like a rogue AI)

Then examine how this external conflict triggers or exacerbates the protagonist’s internal struggles—their fears, insecurities, moral dilemmas, or unresolved trauma. For example, in her memoir Wild, Cheryl Strayed’s grueling journey along the Pacific Crest Trail mirrors her internal struggle with grief, with each physical challenge symbolizing a step toward healing her emotional wounds.

Here are some questions to ask yourself while analyzing the conflict:

Is the central conflict significant enough to sustain the story’s length?

Do the stakes feel high enough to create tension?

Does the conflict escalate naturally throughout the story?

Is the resolution satisfying without feeling too convenient?

Let’s now focus on the place of the story.

5. Evaluate the Setting’s Impact

The time and place of a story can be deeply significant. The best settings do more than just establish location—they also create natural obstacles for characters, reflect or contrast their internal state, and overall influence the mood and atmosphere of the story.

For example, in Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, the economic recession forces the protagonists to move from vibrant New York City to a quiet Missouri town. This setting shift not only creates tension but also serves as a physical manifestation of their deteriorating marriage.

Think of the historical period and how it affects the language, atmosphere, and social circumstances of the story. Ask yourself: For each major scene, is this the most effective location? Could changing the setting enhance emotional impact or create more interesting challenges?

Another subtle-but-major component to analyze is the story’s narrator.

6. Evaluate the Point of View (POV)

The perspective from which the story is told is fundamental. Who is the narrator? Are they a first-person narrator, a third-person narrator who is an important participant, or a third-person narrator who is merely an observer?

Each POV choice comes with benefits and limitations. For example, the first-person creates immediacy and intimacy but restricts information to what that character knows, while the third-person omniscient offers flexibility but can create emotional distance from characters.

The most important factor is whether the POV fits the story. Then, make sure that it is consistent throughout. This means there’s no “head hopping,” which consists of unexplained shifts from one character’s thoughts to another’s.

Flynn’s use of alternating first-person perspectives in Gone Girl allows readers to experience both sides of a toxic relationship, with each narrator revealing themselves to be increasingly unreliable. A fitting choice for a psychological thriller.

Next, focus on the story’s meaning.

7. Identify the Main Themes

What is the main idea or perspective that the author is trying to explore? A story should leave some sort of impression on the reader. At best, it should stretch their thoughts on what it means to be human.

A story’s theme can cover a wide range of topics, from a humorous take on our struggle with ever-advancing technology to a more serious exploration of the hidden suffering caused by domestic abuse.

As you read, ask yourself:

Does it explore interesting and meaningful ideas/topics?

What observations does it make about human nature or society?

Make sure the theme unfolds naturally throughout the story rather than being explicitly stated—this will make the message far more impactful.

Also, you should consider the author’s background and the historical period in which the work was written to better understand what they might be commenting on. For example, having a good grasp of the Victorian context of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre can help you understand why Jane’s desire for independence was so revolutionary.

Finally, some literary “technicalities”…

8. Pay Attention to Literary Devices

Literary devices are writing techniques that can enhance storytelling, deepen a work’s emotional impact, or subtly highlight its themes, and a good story employs at least some of them.

Here are some of the most popular ones to keep an eye on:

Symbolism: Objects or events representing broader ideas

Foreshadowing: Clues hinting at future events, creating suspense

Irony: Contrasts between expectations and reality, increasing tension or humor

Metaphors: Comparisons that make descriptions more vivid

Imagery: Descriptive language that appeals to the senses and immerses readers

Tone and Mood: The author’s attitude (tone) and the emotional atmosphere they are trying to evoke (mood) to influence readers’ perceptions

When assessing a piece of fiction, try to spot them and see if they can be implemented better (or provide suggestions on how to implement them if they aren’t already).

9. Present Your Analysis Effectively

Take all of your notes and bring them together in a single document. If you’re providing feedback to authors, lead with strengths before addressing weaknesses, and pair criticism with actionable solutions.

Use specific examples from the text to support your observations rather than making vague statements. For instance, instead of noting “weak dialogue,” cite specific exchanges and suggest improvements.

Maintain a balanced perspective by acknowledging what works alongside what needs to be addressed. Frame your feedback as opportunities rather than failures—for example, “this scene could build more tension by...” instead of “this scene fails to build tension.”

Finally, prioritize your feedback by focusing on fundamental issues (plot holes, character inconsistencies) before stylistic concerns. Remember that your analysis should ultimately help strengthen the story while respecting the author’s unique voice and vision.

Like any skill, story analysis gets easier with practice. Start by applying these techniques to short stories before tackling longer works. You’ll gradually develop sharper instincts and a more nuanced understanding of narrative craft—making you not just a better editor but a more insightful reader as well.

Ready to take your story to the next level? Check out ProWritingAid’s Manuscript Analysis or Chapter Critique to get actionable feedback on your story’s plot, characters, setting, and other key elements.