The extended metaphor is a powerful literary device for exploring complex ideas. We encounter extended metaphors in all forms of writing, from Shakespearean plays to fantasy novels to song lyrics in pop culture.

So what exactly is an extended metaphor, and what purpose does it serve? The short answer is that an extended metaphor is a metaphor that continues throughout multiple sentences, multiple paragraphs, or even an entire poem or story.

In this article, we’ll explain how this literary device works, give you five simple steps for building your own extended metaphor, and show you some famous examples of extended metaphors from literature.

Extended Metaphor Definition and Meaning: What Is It?

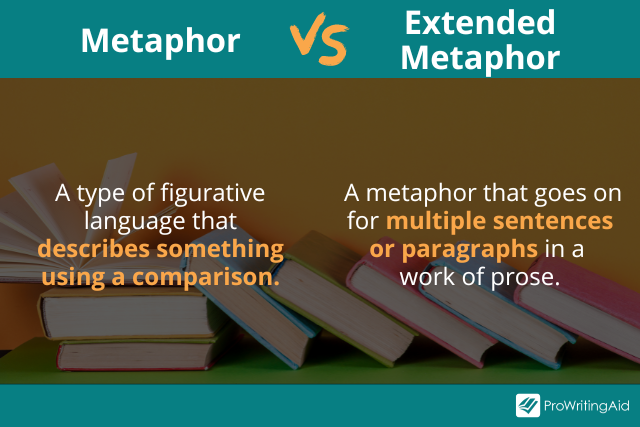

A metaphor is a type of figurative language that describes something using a comparison. Here are some common examples of simple metaphors that you might hear every day:

- “Time is money.”

- “I’m a diamond in the rough.”

- “Laughter is the best medicine.”

An extended metaphor refers to a metaphor that the author explores in more detail than a normal metaphor. It can go on for multiple sentences or paragraphs in a work of prose, or multiple lines or stanzas in a poem.

Sometimes, an extended metaphor can even be referenced repeatedly throughout the course of a story or novel, collecting new meaning as the story progresses.

Here’s a quick example of the difference between a metaphor and an extended metaphor.

- Metaphor: “Her fury was a hammer.”

- Extended metaphor: “Her fury was a hammer. Whenever she got angry, everyone around her looked like a nail. She wished she could wield her anger like a precision tool, but with a hammer there was no room for finesse, only blunt violence. Every time she got in an argument, out came the hammer, striking at not just the person she was arguing with but also her parents, her siblings, and even her pet dog.”

What’s the Structure of an Extended Metaphor?

An extended metaphor takes a central comparison and expands it using more specific details.

Usually, an extended metaphor starts with a simple statement equating two things, such as “Her fury was a hammer.” Then, the author weaves in more details to explain what they mean by that comparison. Each detail should add more nuance to the initial statement, helping the reader understand what the author is trying to say.

When You Should and Shouldn’t Use Extended Metaphors

A well-written extended metaphor can be very powerful, but an unnecessary or convoluted one can make your reader scratch their heads or even stop reading entirely.

So how do you know when you should and shouldn’t use extended metaphors?

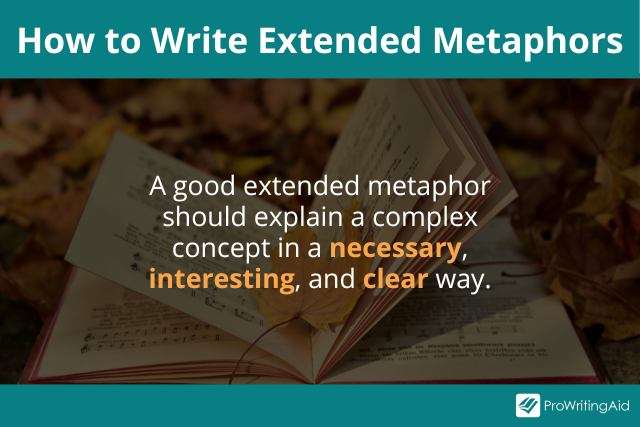

The answer is simple: just remember that a good extended metaphor should explain a complex concept in a necessary, interesting, and clear way.

The three keywords in the sentence above are necessary, interesting, and clear. A successful extended metaphor needs to meet all three criteria.

Let’s look at each of these rules in more detail.

Rule 1: Make Sure It’s Necessary

Necessary means that the concept you’re explaining with your extended metaphor is truly important enough to warrant a detailed explanation. If the extended metaphor isn’t essential to the story, it will only waste your readers’ time.

Consider this example of an unnecessary extended metaphor: “My mosquito bites were an open flame, and I was a moth. They burned me every time I scratched them, but I just couldn’t stop.”

This metaphor makes sense, but unless the narrator’s mosquito bites are particularly important to the story, the reader doesn’t need to hear about them in so much detail.

You could just write, “I couldn’t stop scratching my mosquito bites,” and move on, rather than devoting an entire paragraph to explaining how itchy they are.

Rule 2: Make Sure It’s Interesting

Interesting means that the metaphor provides an original, funny, or thought-provoking insight. If your extended metaphor isn’t interesting, it will just bore your readers.

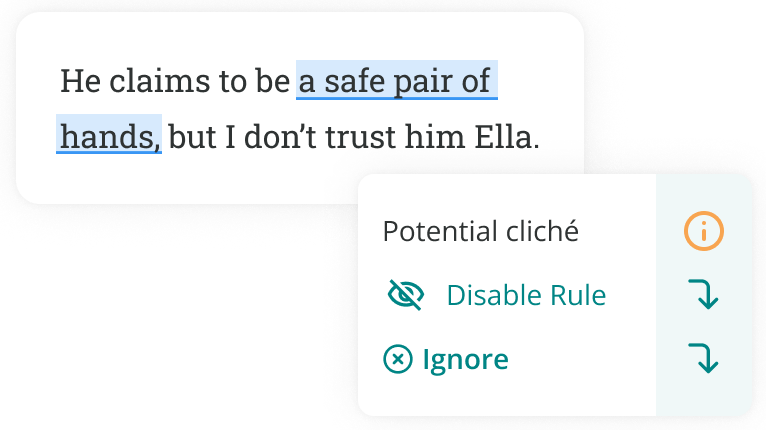

Consider this example of an uninteresting extended metaphor: “Her eyes were a blue ocean. I wanted to swim in them forever.”

This metaphor makes sense—we can all picture the color of the ocean—so the meaning is clear. Unfortunately, it’s not particularly interesting. Blue eyes are often compared to oceans, so this paragraph feels clichéd and unnecessary.

ProWritingAid’s Clichés Report highlights overused expressions in your writing so you can make sure your metaphors are original.

Rule 3: Make Sure It’s Clear

Finally, the third keyword, clear, means that the metaphor helps the reader understand the complex concept better. If your extended metaphor isn’t clear, it will baffle your readers and make them scratch their heads.

Consider this example of an unclear extended metaphor: “Human society is a trash can full of plastic water bottles that have been set on fire. It’s hot, smells bad, and releases a lot of fumes.”

This metaphor is interesting—we’ve certainly never heard the phrase “a trash can full of plastic water bottles that have been set on fire” before—but it isn’t clear.

It doesn’t help us understand human society any better than we did before we read it. If anything, it just made us feel more confused.

Remember those three keywords—necessary, interesting, and clear—and make sure all your extended metaphors fulfill all three. This way, your extended metaphors add to your writing, rather than detract from it.

How to Use an Extended Metaphor in 5 Steps

Writing an extended metaphor might feel daunting at first, but you can break it down into simple steps. Here are five steps you can use to build an extended metaphor.

Step 1: Find a Concept You Need to Explain

The purpose of an extended metaphor is to explain a concept more clearly to the reader, so the first step is to identify a complex concept that you need to explain.

Here are some examples of things that you might want to describe using an extended metaphor:

- Abstract emotions (such as grief, anger, joy)

- Philosophical concepts (such as death, justice, human society)

- Characters’ personalities

- Unusual settings, situations, or environments

Step 2: Choose a Concrete Image to Explain That Concept

Now that you know the complex concept you need to explain, it’s time to choose a point of reference to help you describe it to the reader.

Think about concrete images, objects, or references that are already clear in your reader’s mind.

For example, you might come up with the following comparisons to use as your primary metaphor:

- Her grief was a wall she couldn’t cross.

- Justice is a boat sailing through stormy waters.

- My brother has the personality of a cactus.

In each of these cases, an abstract concept (grief, justice, and a character’s personality) is compared to a specific concrete image (a wall, a boat, and a cactus). The concrete images help the reader understand what the author is trying to say about the abstract concept.

Step 3: Check the Comparison Is Necessary, Interesting, and Clear

Remember those three rules we talked about earlier? Now’s the time to make sure your initial metaphor passes all three tests: necessary, interesting, and clear.

If your central comparison is unnecessary, uninteresting, or unclear, it will just bog down your writing. It’s common for amateur writers to include extended metaphors they don’t need as an attempt to sound profound or original.

Step 4: Expand on the Central Comparison

The central comparison on its own is just a normal metaphor. To make it an extended metaphor, you need to extend it over several lines or passages.

This extension often involves smaller metaphors that expound on the primary metaphor. It takes the central comparison and examines the question, “How are these two things alike?” and provides a more detailed and specific answer.

Let’s look at an example from Step 2: “My brother has the personality of a cactus.” How exactly is the brother’s personality similar to a cactus? Maybe he pricks everyone who gets too close because he prefers to be left alone. Or maybe he can survive in harsh conditions, subsisting with barely any sleep, water, or human contact.

Adding these specific details turns a normal metaphor into an extended metaphor.

Step 5: Repeat the Comparison Throughout the Piece

If you want to, you can revisit your extended metaphor multiple times throughout your book, poem, or story. That way, you can create a sustained metaphor that gathers meaning over time.

This final step is optional, but can be extremely powerful if used correctly. Just make sure each new repetition is also necessary, interesting, and clear.

Extended Metaphor Examples in Literature

Here are some extended metaphor examples from works of English literature: novels, plays, poetry, and nonfiction.

In each example, see if you can spot the main comparison and the ways the author expands on it throughout the passage.

Example 1: The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

“I wait. I compose myself. My self is a thing I must now compose, as one composes a speech. What I must present is a made thing, not something born.”

Example 2: As You Like It by William Shakespeare

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts.”

Example 3: The Magicians by Lev Grossman

“But walking along Fifth Avenue in Brooklyn, in his black overcoat and his gray interview suit, Quentin knew he wasn’t happy.

Why not? He had painstakingly assembled all the ingredients of happiness. He had performed all the necessary rituals, spoken the words, lit the candles, made the sacrifices. But happiness, like a disobedient spirit, refused to come. He couldn’t think what else to do.”

Example 4: The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin

“So you must stay Essun, and Essun will have to make do with the broken bits of herself that Jija has left behind. You’ll jigsaw them together however you can, caulk in the odd bits with willpower wherever they don’t quite fit, ignore the occasional sounds of grinding and cracking. As long as nothing important breaks, right? You’ll get by. You have no choice. Not as long as one of your children could be alive.”

Example 5: On Writing by Stephen King

“I did as she suggested, entering the College of Education at UMO and emerging four years later with a teacher’s certificate… sort of like a golden retriever emerging from a pond with a dead duck in its jaws. It was dead, all right. I couldn’t find a teaching job and so went to work at New Franklin Laundry for wages not much higher than those I had been making at Worumbo Mills and Weaving four years before.”

Example 6: “To a Young Poet” by Edna St. Vincent Millay

“Time cannot break the bird's wing from the bird.

Bird and wing together

Go down, one feather.

No thing that ever flew,

Not the lark, not you,

Can die as others do.”

Example 7: Palimpsest by Catherynne Valente

“The keeping of lists was for November an exercise kin to the repeating of a rosary. She considered it neither obsessive nor compulsive, but a ritual, an essential ordering of the world into tall, thin jars containing perfect nouns.”

Conclusion on the Extended Metaphor

There you have it—a complete guide to extended metaphors! I hope this article helped you learn more about this versatile literary device.

Don’t forget to run your writing through ProWritingAid to make sure you’re using figurative language as successfully as possible. Our tool can help you avoid clichés, strengthen your imagery, and more.

Can you think of any extended metaphors from your favorite books? Share them with us in the comments!