Many writers begin their stories by drafting out dialogue first.

Often, these initial imagined conversations among their characters are rough or incomplete, and don’t do the best work of unfolding the story or moving it along. But they do provide a starting point.

The author can then layer in narrative exposition and other storytelling elements, while revising and refining the dialogue to ensure it fulfills the needs of the story.

Dialogue’s Functions

Though dialogue can serve many functions in fiction, three of its primary purposes are to:

- establish the tone and atmosphere of a scene

- reveal your characters

- advance your storyline

Function 1: Establishing Tone and Atmosphere

Characters’ verbal exchanges reveal their moods and attitudes, which set a tone for the scene. Compare this exchange:

"Manny!" Jeff called from the yard next door. "I’ve been meaning to ask about that car I’ve seen in your driveway every night this week."

"Mind your own business." Manny trudged into his garage.

to this one:

"Manny!" Jeff called from his yard next door. "I’ve been meaning to ask about that car I’ve seen in your driveway every night this week.”

Manny approached the hedge between their houses. “It’s been such a relief to get help with Mom. I can finally get some sleep at night.”

In the first, Manny is clearly annoyed by his neighbor’s curiosity. In the second, Manny is more eager to share details and the tone is friendlier.

Dialogue can also reveal setting. The setting, in turn, contributes to the scene’s atmosphere.

In the example above, Manny and his neighbor are both outside in their yards. We know that from the bits of description interwoven between the speakers’ words, specifically, Jeff called from his yard next door and Manny approached the hedge between their houses. (These are action beats, which we’ll discuss further below.)

That these men are neighbors and they’re having this exchange over their hedge tells you something about the atmosphere of this scene. If the neighbors were having this conversation after bumping into each other at the grocery store, or if they were talking in Manny’s living room where his mom’s hospice bed was set up in the corner, the atmosphere of the conversation would be quite different.

Function 2: Revealing Characters

A conversation between two or more characters can provide readers with a deeper understanding of those characters than even the most well-written exposition. That’s because effective dialogue draws readers into the characters’ lives by showing rather than telling.

A few lines of dialogue can disclose a character’s personality, backstory, and relationships with other characters. Great dialogue can reveal a character’s emotions and the way those emotions change over time. It can help the reader understand what motivates your character to act in the ways they do and why they’re after whatever their aim or goal is in the story.

Function 3: Advancing Your Storyline

While dialogue can convey character details, it does double-duty by advancing your storyline.

Plot details the reader didn’t know about yet can be revealed through dialogue, which will contribute to reader anticipation and keep them turning the pages. Dialogue that reveals meaningful and relevant information to help the reader better understand the characters and follow the plot naturally advances your story.

Dialogue’s Form

While dialogue is clearly an exchange of words between two or more characters, effective dialogue isn’t just what your characters say to one another. It also consists of dialogue tags and action beats.

Dialogue Tags

Dialogue tags are those short phrases that signify to readers who is speaking: Martha said, he asked, and the like. The simpler the dialogue tag, the better. Colorful verbs, such as exclaimed, interjected, or screeched, might seem to elevate the writing, but they actually make it sound amateurish, as do adverbs, such as:

“Oh, it’s such a relief to get some help with Mom,” Manny said tiredly.

If you want to show Manny is tired, rather than using a dialogue tag with an adverb attached, use an action beat along with his words.

Action Beats

An action beat is a short narrative passage that describes the speaker’s movements, facial expressions, and even their internal thoughts. Beats can reveal your character’s emotions and show how your character interacts with other characters and with the setting.

Remember the two beats identified in the example above: Jeff called from his yard next door and Manny approached the hedge between their houses? Don’t forget that when people talk, they’re always simultaneously doing something. So if you want to show Manny is tired, have him slump his shoulders or lean on his shopping cart to hold himself up. In short, action beats illustrate what else is going on in a scene besides just the characters’ conversation.

When written well, an action beat can replace a dialogue tag, fulfilling the same purpose of letting the reader know who’s speaking while also giving a sense of the character’s personality and/or the scene’s setting. The action beat is included in the same paragraph as the character’s spoken words to indicate that the person acting is also the person speaking.

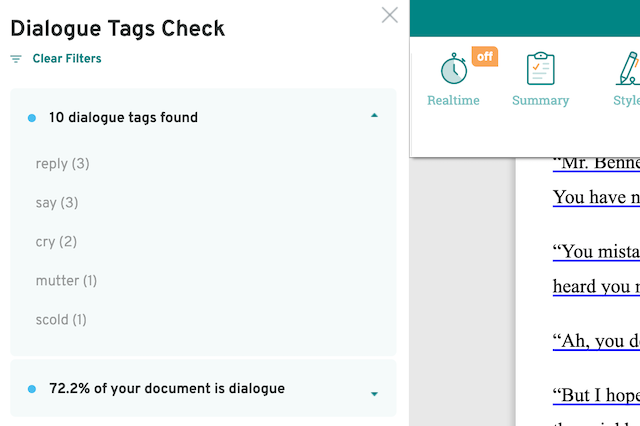

Use ProWritingAid’s Dialogue Check to highlight your dialogue tags.

When you see them in a list like this, it’s easier to spot where you might need to substitute a distracting dialogue tag with an action beat.

10 Tips for Writing Believable Dialogue

Authors often strive to make their dialogue realistic, but what they need to aim for is believable dialogue. In real conversations, we cut each other off, we change topics mid-sentence for no apparent reason, we interrupt each other. If your characters do these things as often as we do them in real life, they won’t be credible.

Here are ten ways to create believable dialogue.

Leave the chit-chat and social niceties out of your story. Avoid meaningless conversation. Include only discussions that reveal something necessary about the character and/or plot.

Give your characters distinctive ways of speaking. An assertive character won’t sound the same as a shy one. Make sure the words they use match their personality.

Similarly, use an appropriate personal vocabulary for your characters. Make their dialogue fit their background and occupations. A dockworker might swear more than a schoolteacher; he won’t know as much about grammar nor care as much about using it properly.

Consider how much your characters say and how often they talk compared to other characters. An introverted character would likely be more concise or reserved in a group conversation than an extroverted character. An enthusiastic businesswoman might be chattier than an overtired mother of five.

Also, take into account who they’re speaking to. A teenage character would probably speak to his mother differently than he would to his best friend.

Avoid “info dumps.” That’s when characters tell one another things they already know because the author couldn’t figure out any other way to inform readers of the same information. Info dumps sound awkward and unnatural, and they insult readers’ intelligence. Find another way to convey the information to the reader.

Keep the dialogue concise. Lengthy discussions aren’t necessary to reveal character personalities, perspectives, and motivations or pertinent plot information. Avoid monologues. Not only can they be tiring for the reader but they often sound unnatural. Characters, like people, interject questions or responses to what the speaker is saying. If you decide a monologue is necessary in a particular scene and is appropriate for the character, use action beats and narrative exposition to break it up.

Vary the lengths of each character’s spoken words, as well as the structure of the lines of dialogue. Avoid ending every line with a dialogue tag. Instead, place the tag in the middle of the dialogue occasionally, then insert action beats in place of some end-of-line dialogue tags.

Don’t use dialect. Dialect is writing a passage of dialogue to mimic the person’s way of speaking. While it might seem this would make a character more authentic, it usually simply annoys readers. Respect your readers by giving them enough description to understand a character is, say, British, and allow them to “hear” the accent in their own imagination.

Create conflict in your dialogue by giving the characters who are having the conversation opposing agendas. Dialogue between two or more characters who want things that work against each other is more compelling than conversation between agreeable characters. Consider whether your characters would be direct or elusive about their agendas.

Final Words of Advice

Ensure your dialogue is advancing the storyline by having at least one of the characters undergo some change over the course of the discussion. The character either should experience a shift in mood or attitude, or they should find out something they didn’t know at the beginning of the conversation.

Lastly, during the editing process, read your entire manuscript aloud, paying special attention to the dialogue. If it doesn’t flow or you trip over your words, it won’t sound right to the reader either.

Don’t miss these other great articles on the ProWritingAid blog about dialogue:

- How to Punctuate Dialogue Correctly

- 10 Dialogue Mistakes to Avoid in Your Novel

- 5 Tricks for Using Dialogue to Write Truly Captivating Characters

One final aspect of dialogue that shouldn’t be ignored in fiction is the use of internal dialogue to reveal the thoughts and emotional state of a character. For more on internal dialogue, check out Internal Dialogue: The Greatest Tool for Gaining Reader Confidence.