Every novel has a narrator—the voice that will be doing the telling on your behalf.

An omniscient narrator has an all-knowing perspective on your story. They are usually not a character in the book, but instead seem to speak as if they are writing the story.

There are many different types of narrators and choosing the correct one can make or break how your reader connects with your storytelling.

In this article we will explain one of the many narrative or point-of-view (POV) options available to you, that of the omniscient narrator. We’ll explain exactly what it is (and what it’s not), how to use it correctly, and what pitfalls to avoid when using it.

What Are the Four Narrative Voices?

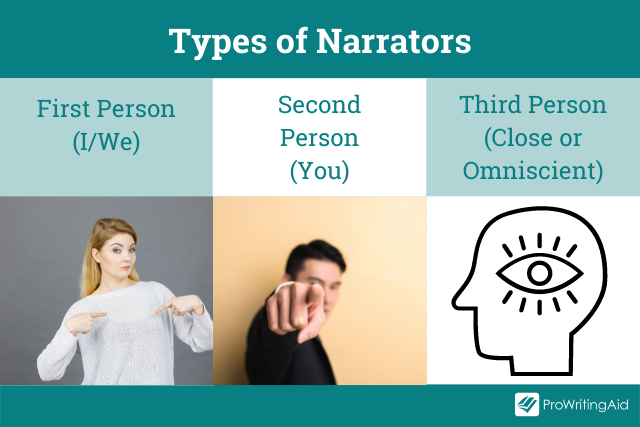

Let’s take a step back for a moment to remind ourselves of the four types of narrator that are available to us when telling a story.

1. First-Person Narrative Voice

The first-person narrator tells their own story since only they can see and experience it. This means they can provide us with limited insights into what’s going on in their world. An example of first-person narrative is Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird:

“Dill left us early in September, to return to Meridian. We saw him off on the five o’clock bus and I was miserable without him until it occurred to me that I would be starting to school [sic] in a week. I never looked forward more to anything in my life.“

—To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

We only get to witness the events of this novel through the eyes of Scout and what she chooses to share with us.

2. Second-Person Narrative Voice

The second-person narrative voice is an unusual one in fiction and is more commonly found in non-fiction, particularly in self-help books where the author wants to reach out to you.

Examples of the second-person POV in fiction can be found in Spill Simmer Falter Wither by Sara Baume, The Book of Rapture by Nikki Gemmel, and Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney.

Here’s an example:

“You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning. But here you are, and you cannot say that the terrain is entirely unfamiliar, although the details are fuzzy.”

—Bright Lights, Big City, Jay McInerney

This is a tough one to get right and can be disorienting for the reader, so make sure you read as many books with this POV as possible before deciding that it’s the one for you.

3. Third-Person Narrative Voice

A third-person narrative voice can also be called a limited omniscient or “close” third-person POV. This is the most common POV in modern fiction.

Here the narrative voice adheres to a single character to tell a story from their point of view. This means that what you learn in the course of the story is based only on this character’s experience of the world around them—hence the term “limited.”

It is not uncommon to have multiple third-person POVs in one work of fiction—not to be confused with the omniscient third. Think of Liane Moriarty’s Nine Perfect Strangers, which is currently a big hit on the small screen.

In the novel, the author alternates the POVs, with each chapter dedicated to one particular character. So we gain multiple characters’ insights into the events of their lives, however, none of them has any knowledge into another’s without direct experience.

Romance writers also commonly employ third-person limited POVs to provide insight into both of their romantic heroes’ inner lives. So you’ll often see the story being recounted from each of their perspectives.

A great example is Tia Williams’ Seven Days in June. We learn about Eva and Shane in chapters that alternately focus on one, then the other’s backstories. This helps keep the storytelling clean without getting muddled up by multiple perspectives.

4. Omniscient Third-Person Narrator

And now for our big guy: the third-person omniscient narrator. The star of this show. The one that knows all, sees all. The one we’ll be looking at for the rest of this article. Read on for a deep-dive on what exactly the omniscient third-person narrator is.

What Is an Omniscient Narrator?

The third-person omniscient narrative voice is a classic narrative style, going as far back as Homer’s Illiad.

You’ll recognize it from canonical works such as:

- William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies

- Toni Morrison’s Beloved

- Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God

And more recent bestsellers such as:

- Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing

- Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You

- Brit Bennett’s The Mothers

The word omniscient has its roots in Latin and is a compound word, bringing together the prefix omni-, which means “all,” and the verb scire, which means “to know”—omniscient literally means knows all.

The omniscient narrator knows your characters’ backstories, their motivations, their emotional states, and internal chatter.

In essence, they are your story’s “deity.”

The omniscient narrator is knowledgeable and generally shows no prejudice or judgement towards the characters in the book, although there are omniscient narrators who do like to freely dish out opinions and judgements.

Just think of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” That’s rather opinionated, wouldn’t you say?

In the rarest of cases we can have an omniscient first-person narrator. An example of this is The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. Here, our narrator is none other than Death themselves, which is probably the only way you’d get away with an omniscient first-person narrator—unless you make it God—but my guess is that it would take a fair bit of chutzpah to write that.

Why Use an Omniscient Narrator?

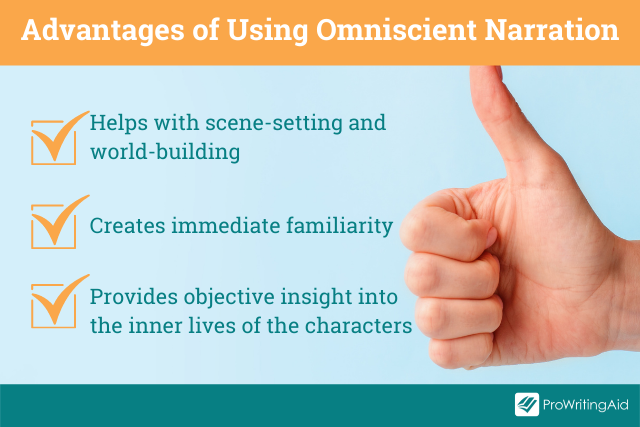

An omniscient narrator can quickly create feelings of connectedness and familiarity in your reader. The narrator can set the scene, lay out existing tensions, and get the story rolling without having to rely on the appearance of one particular character’s voice to do the same job.

Many authors of literary classics from the 18th and 19th centuries employ an omniscient narrator in their often epic novels.

With so many of these stories spanning years, if not decades, and containing dozens of main characters, having an all-knowing narrator on hand to direct the action and provide background and missing details is the ideal way to keep the narrative flowing without losing its readers.

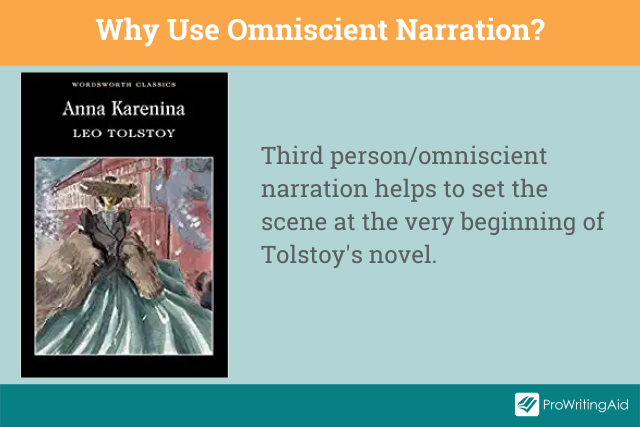

Let’s look at this example:

“Everything was in confusion in the Oblonskys’ house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. This position of affairs had now lasted three days, and not only the husband and wife themselves, but all the members of their family and household, were painfully conscious of it.”

—Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy

Here we are, at the very beginning of Tolstoy’s famous novel. It is thanks to the third person omniscient narrator that we’re immediately dropped into the scene: the family’s unease is palpable, the house filled with tension, and we can vividly imagine the couple’s misery.

But don’t be fooled into thinking that the omniscient narrator is a thing of the past or only employed to help navigate novels of epic proportions. Celeste Ng’s 2014 novel Everything I Never Told You also employs an omniscient POV. Here’s an excerpt from the very first paragraph:

“Lydia is dead. But they don’t know this yet. 1977, May 3, six thirty in the morning, no one knows anything but this innocuous fact: Lydia is late for breakfast. [...] Driving to work, Lydia’s father further nudges the dial toward WXKP, Northwest Ohio’s Best News Source, vexed by the crackles of static. On the stairs, Lydia’s brother yawns, still twined in the tail end of his dream. And in her chair in the corner of the kitchen, Lydia’s sister hunches moon-eyed over her cornflakes, sucking them to pieces one by one, waiting for Lydia to appear. It’s she who says, at last, ‘Lydia’s taking a long time today.’ ”

—Everything I Never Told You, Celeste Ng

Interestingly, the first drafts of this novel were originally written with multiple, close-third POVs. However, the author explains that:

“What I ended up with was a very fractured narrative: five point-of-view characters, three timelines, innumerable flashbacks. Important information got buried in the barrage of confession. [...] You had to piece the story together from a cacophony of voices talking at once. That can work in some novels, but it wasn’t working here. No one was telling the story; five people were telling five different stories.”

—Writing the (Quiet) Omniscient Narrator, Celeste Ng

So she set out to rewrite her novel from an omniscient point of view, loving the flexibility that this POV provides:

“When there are many voices, the narrator can order them just as a teacher moderates a discussion, letting one have a say, calling on another to respond, pointing out the connections between what they’ve said. When characters disagree, the narrator can give context so we know who’s telling the truth—or so we can see how much (or little) of the truth each is telling. When events from the past reverberate into the present, the narrator can guide us from one time to the other and show us how they link. And throughout, the narrator can remind us of things the characters have forgotten, or never knew, so we can understand what’s happening—and why.”

—Writing the (Quiet) Omniscient Narrator, Celeste Ng

In essence, the purpose of the omniscient narrator is to delegate space to the various characters in your story while also providing context and background information that allows the narrative to flow. No small feat!

How Do You Know If It’s an Omniscient Narrator?

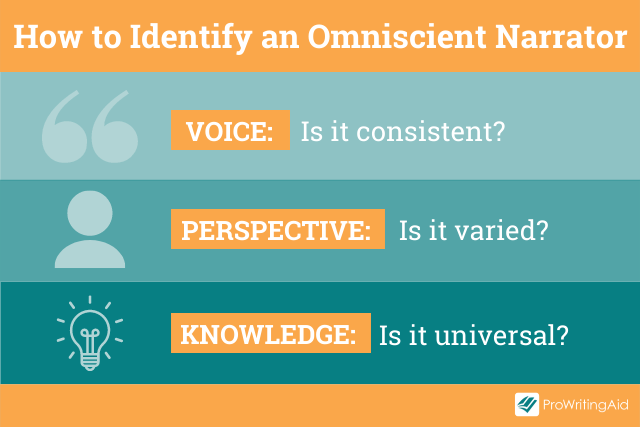

It can be tricky to pinpoint whether a narrator is omniscient or whether the story is being told from multiple limited POVs.

Here are a few tips to help you work it out:

- Whose voice are you hearing? Is it the same voice throughout the novel? Does it remain unchanged regardless of whose character’s story it’s delving into? If so, you have an omniscient narrator.

- Look at whose perspective the story is being told from. Do we only get one or two people’s takes on what’s happening, or are we getting multiple, varied perspectives? If so, it’s likely an omniscient narrator.

- Is there anything the narrator doesn’t know about? If the narrator can provide details of everything that’s been and that’s currently happening, and even hint at what’s yet to come, you have yourself an omniscient narrator.

If you’re ever in doubt about the type of narrative voice in a book, simply look at the pronouns employed:

- “I/We” indicates a first-person narrator

- “You” is the rare second person

- “He/She/They” means the story is told in the third-person narrative voice.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Creating an Omniscient Narrator

Writing an omniscient narrator can be tricky and has gone a bit out of fashion in modern literature. One of the best things you can do is to read as many novels written with an omniscient POV as possible to see just how it’s done.

In the meantime, here are some common pitfalls to avoid while writing an omniscient narrator into your tale.

1. Show, Don’t Tell

Just because your narrator has all the knowledge and insight and could, very quickly, tell your reader exactly how a character is feeling or what they’ve been through doesn’t mean that they should. Why not let your readers experience all that for themselves?

After all, that’s why we read, right? Allow your readers to get the full, immersive experience.

Celeste Ng does this beautifully in her Everything I Never Told You by appealing to as many senses as possible in her writing. Look at this example:

“She dug in her purse for a handkerchief and touched its corner to her palm [...], the handkerchief blotched scarlet. [...] She wanted to touch it, to lick it. To taste herself. Then the cut began to sting, and blood began to pool in her cupped palm [...].”

The author could have simply stated that Marilyn cut her hand on a shard of glass. Instead, she gives us a full sensory experience, appealing to our sense of touch, sight, and taste in one brief paragraph.

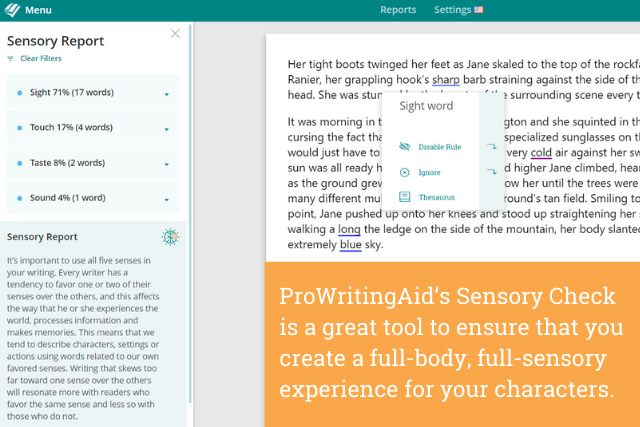

ProWritingAid’s Sensory Check helps you create a full-body, full-sensory experience for your characters. It shows you how many of each type of sense word you’ve used so you don’t favor one or two of your characters’ senses over the others.

Try ProWritingAid’s Sensory Check on your own writing with a free account.

Remember while writing your omniscient narrator, even though they know it all, it’s still better to show. So don’t tell!

2. Stay Consistent

Make sure you stay consistent in your narrative voice. Some omniscient narrators have universal, detached voices. Some are more specific. One good example of this is in Brit Bennett’s The Mothers, where a group of church ladies lend their voices to the omniscient narrator:

“When we first heard, we thought it might be that type of secret, although, we have to admit, it had felt different. Tasted different too. All good secrets have a taste before you tell them, and if we’d taken a moment to swish this one around our mouths, we might have noticed the sourness of an unripe secret, plucked too soon, stolen and passed around before its season.”

As an aside, notice how Brit Bennet, too, appeals to various senses in just this paragraph!

Whether your omniscient narrator has a distinct personality, like the mothers here, or not, make sure you stay consistent with your voice so as not to confuse your readers.

3. Don’t Go Head Hopping

Head hopping is when you move between multiple characters’ perspectives within the space of a paragraph, or even a sentence.

This is easily done as your narrator knows exactly how everyone’s feeling. However, this doesn’t mean that you should jump from one character’s head to another in the course of a paragraph to reveal everyone’s innermost thoughts and expectations.

This can be confusing and disorienting for your reader and is just plain bad form, so don’t do it (regardless of what kind of narrator you write!). Instead, start a new scene whenever you want to switch perspective.

Should You Use an Omniscient Narrator?

Writing an omniscient narrator comes with plenty of challenges and you can see why it’s a style that’s gone out of fashion in modern literature.

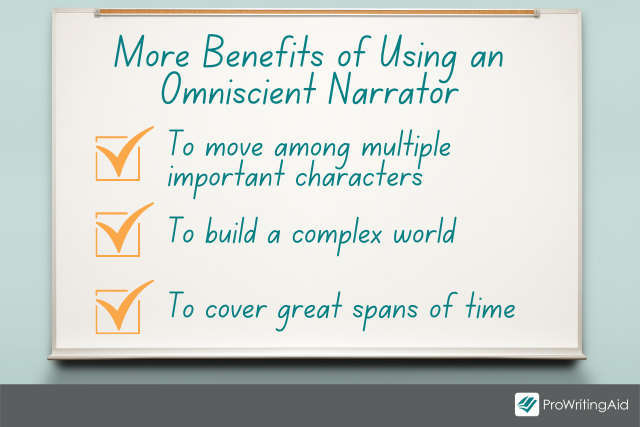

However, it is a great choice if you have multiple characters whose thoughts and inner workings are of equal importance to the development of your story. It can add to world-building, especially if yours is a complex one (think fantasy fiction) and it’s helpful if your story spans a big chunk of time or moves back and forth in its chronology.

Whatever type of narrator you choose to help tell your story, remember to stay consistent when it comes to voice and perspective. And know that the ProWritingAid Writer’s Community is just a click away to help with any writing questions that you might have.