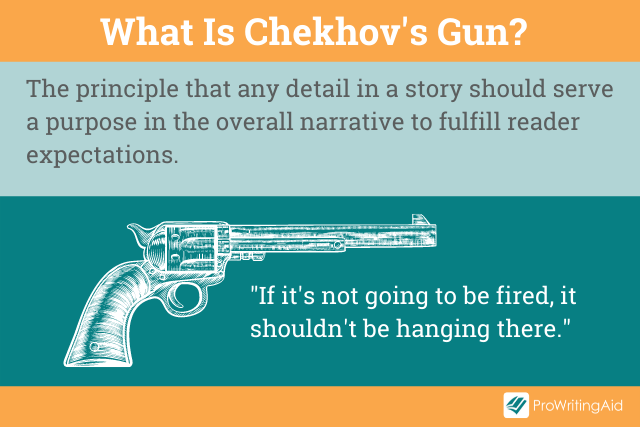

In short, Chekhov’s gun is the principle that any detail in your story should have a purpose in the overall narrative.

Readers will expect any details in your story to have payoff. A writer should not make false promises to readers.

The best part of writing fiction is the ability to create whatever you want. But even with all this freedom, there are still some guiding rules and principles that writers follow.

Chekhov’s gun is one of these principles that help ensure your narrative flows well without disappointing your readers. Read on for a complete guide on Chekhov’s gun.

- What Is the Origin of Chekhov’s Gun?

- What Is Chekhov’s Gun?

- Is Chekhov’s Gun a Type of Foreshadowing?

- What Is the Opposite of Chekhov’s Gun?

- Do I Have to Use Chekhov’s Gun in My Writing?

- How Does Chekhov’s Gun Improve a Story?

- How Do I Use Chekhov’s Gun in My Story?

- What Are Some Examples of Chekhov’s Gun?

What Is the Origin of Chekhov’s Gun?

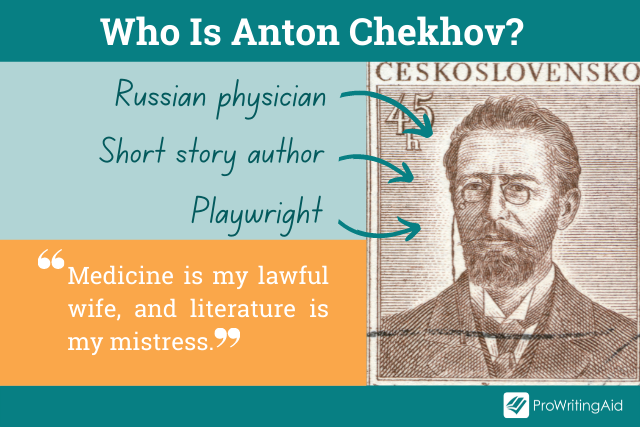

Anton Chekhov was a Russian playwright and author in the late 1800s. He was well-respected for his knowledge of narrative structure, and many consider him one of the greatest short story writers of all time.

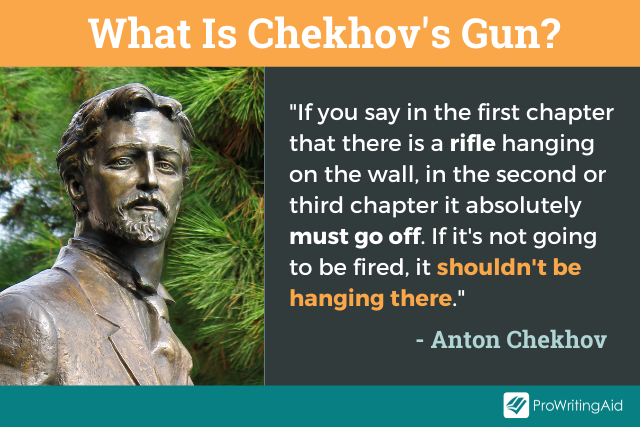

Chekhov’s gun is an idea that came from a piece of writing advice Chekhov gave many times in various communications. The quotes vary, but the advice is the same:

"If you have a pistol on the wall in the first act, it must be fired by the end."

Chekhov’s gun doesn’t just apply to props. Here is a longer quote about writing prose that sums up the advice well:

"Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there."

What Is Chekhov’s Gun?

But my story doesn’t have a rifle, you say! It doesn’t even have a pistol!

Chekhov just liked to use guns to illustrate his point, but his advice is not about the weapons at all. You are probably wondering exactly what Chekhov means by this. Chekhov is referring to the use of details in your story.

Writers create a sort of unspoken contract with readers, according to this principle. That contract states that we include details because they’re important. Readers can trust that if we’ve drawn attention to something, it has significate.

As writers, we promise that we will not create false guns in our stories, so that readers will not expect something that has no payoff.

The Chekhov’s gun principle helps make our writing clearer. No one wants to get bogged down in extraneous information or unnecessary details.

I once attended a community theater play where the directors had clearly never heard of Chekhov’s gun. The set changes between scenes took longer than the scenes themselves. There were a variety of props that the stage crew had to set in just the right positions. Everything from picture frames and vases to full pieces of furniture set the scene.

However, hardly any of these props or set pieces were used. By the end, the entire audience was frustrated with all the time we spent waiting between scenes, only to have no payoff. The play could have easily been an hour shorter.

Readers’ time is precious, and false expectations lead to let-downs. Have you ever finished a book and thought, "But what about that plot line? It was never wrapped up!"

You can avoid this in your writing by following the principle of Chekhov’s gun.

Is Chekhov’s Gun a Type of Foreshadowing?

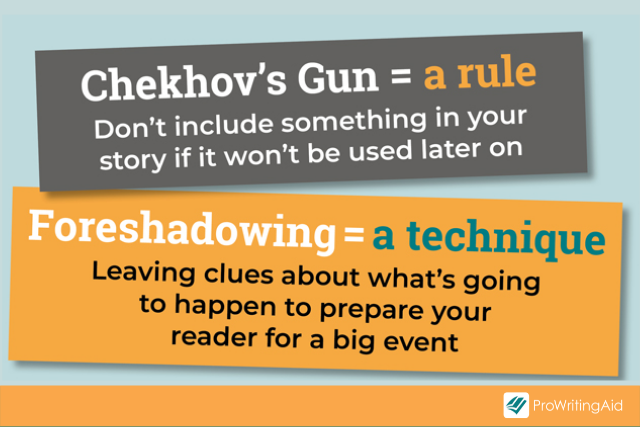

Chekhov’s gun says that any details should serve a purpose to the narrative and be explained later. While this concept is related to foreshadowing, these two ideas are not exactly the same.

What Is Foreshadowing?

Foreshadowing is when a writer drops clues about a plot point that will be revealed later on in the story. These clues are usually intended to be overlooked by the reader. When the big reveal happens, the reader will think, "Oh! That was a clever clue! It all makes sense now!"

An instance of Chekhov’s gun can be a type of foreshadowing. However, Chekhov’s gun is more directly related to reader expectations. In other words, if you draw attention to a gun on the wall in the opening chapter, the reader will know the detail is significant. They can anticipate that it will go off at some point, making it important to the plot.

What Is the Opposite of Chekhov’s Gun?

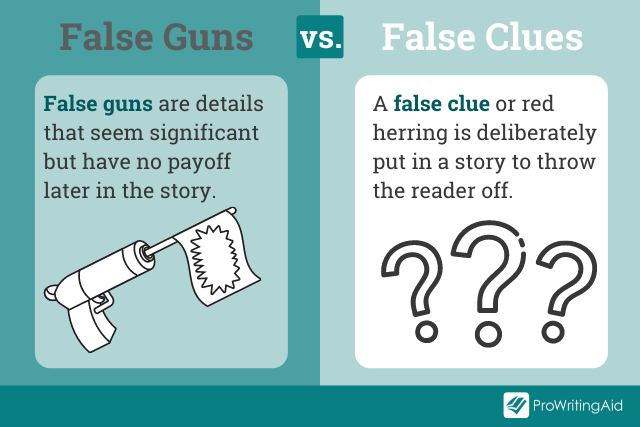

If every detail should have payoff in a story, what about red herrings? If this article is your first time hearing about Chekhov’s gun, you might think that Chekhov’s gun doesn’t account for a literary device like a red herring.

However, it’s not quite that simple. In fact, a red herring is in many ways a type of Chekhov’s gun. Let’s explore.

What Is a Red Herring?

A red herring is a false clue the writer plants deliberately to lead the reader to a false conclusion. This distraction makes the big reveal or truth in a story more shocking because the reader expected another outcome.

Let’s take a look at an example. In Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, the reader spends most of the book expecting Sirius Black to be a Death Eater who wants to kill Harry. These clues are planted throughout the book—Sirius looks like a really bad guy. But Sirius was a red herring. He was framed, and the real bad guy was Peter Pettigrew.

How Are Red Herrings Different from Chekhov’s Gun?

Although a red herring is a false clue, it is not a "false gun". Some might consider a red herring a type of Chekhov’s gun because it does serve a specific purpose to the narrative: misleading the main character (and the reader). The payoff is that the red herring allows the main character (and the reader) to be surprised.

An example of Chekhov’s gun in the same story happens early on in the novel. The Dursleys and Harry hear a news report about an escaped mass murderer. Uncle Vernon is outraged because the news didn’t even say which prison he escaped from.

Rowling draws attention to this story because it is unusual. Later, we learn that the escaped mass murderer was actually Sirius Black. The reason the news didn't report on the name of the prison is because Sirius escaped from a wizarding prison.

Do I Have to Use Chekhov’s Gun in My Writing?

Many writers and scholars consider Chekhov’s gun a crucial component of storytelling. It’s a great principle for guiding your writing to help ensure a cohesive narrative without too many extraneous details.

But is it a law? Well, I suppose it depends on who you ask. Writing fiction is an art, and any rules that apply to the arts are meant to be broken. Writing laws are more guidelines.

So, how seriously should you take Chekhov’s gun?

Well, let’s first consider timing.

Chekhov says a rifle on the wall in chapter one should go off in chapter two or three. Of course, in your story, it might be okay for the rifle to go off later.

Chekhov mostly wrote short stories, not novels, so the pacing of chapters is different. There’s no set time for the payoff, as long as it happens by the end. If you’re writing a series, that payoff could be in a later book.

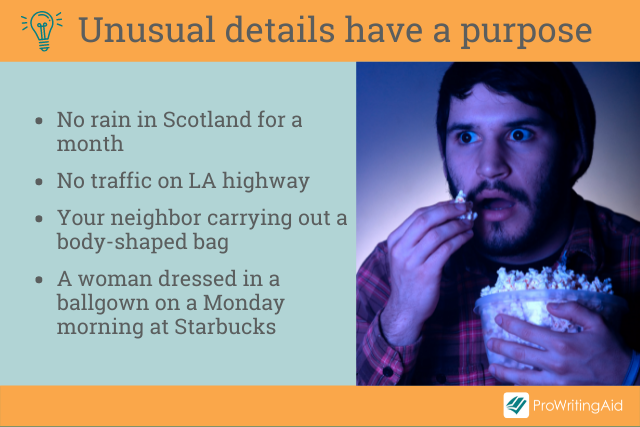

It’s also likely that your writing will include details that don’t fulfill a promise to the reader. A detail’s purpose, such as the weather or the color of a character’s dress, might just be to set the scene and provide sensory detail. That’s okay.

Pay attention to how much time you spend focusing on a detail, whether through description, narration, or dialogue. If you write that there is a plush, oversized armchair in the corner, you’ve successfully illustrated that the room is cozy.

But if you spend two or three sentences describing the color, and the worn spots from age, and the suspicious stain on the right armrest, the chair becomes significant. The reader will expect it to mean something in that scene or later in the story.

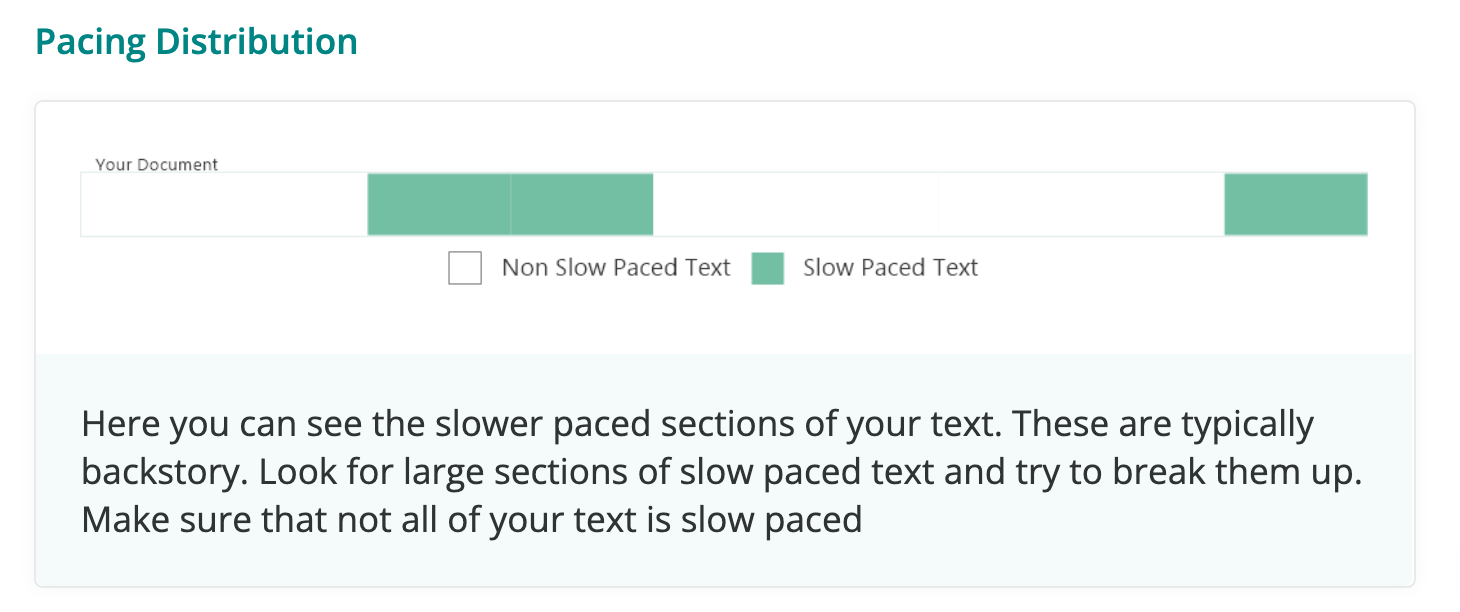

Worried about adding too much detail? ProWritingAid’s Pacing Check will highlight areas it identifies as introspection and backstory.

Once you know where your slower-paced sections are, you can evaluate whether you need less detail or more action.

Try the Pacing Report with a free ProWritingAid account

What Did Ernest Hemingway Think About Anton Chekhov’s Rule?

Chekhov’s gun is a way to make sure your prose is clean and doesn’t have unnecessary details.

Another master of storytelling was Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway also believed in writing tight narratives without purple prose. He believed that readers will assign their own meaning to stories, and so deeper aspects do not need to be explained outright.

But when it came to Anton Chekhov and his guns, Hemingway thought it was a little ridiculous.

Hemingway actually mocked the idea of Chekhov’s gun as a writing principle. In his short story "Fifty Grand," he introduces two characters who are never mentioned again. Life is full of inconsequential details. Hemingway liked them and wanted to readers to assign their own meaning to the details in his stories.

Both Anton Chekhov and Ernest Hemingway were master storytellers with completely different takes on details and payoff. Neither of them were right or wrong, and there is something to be learned from both of them.

How Does Chekhov’s Gun Improve a Story?

Besides eliminating extra information and fulfilling readers’ expectations, Chekhov’s gun can improve a story by building tension.

Imagine an action movie where the characters must disable a bomb. In the background, you hear a constant "tick tick tick" as the clock counts down. The tension is building rapidly until you’re on the edge of your seat. Will they disable the bomb in time?

This example is how Chekhov’s gun works in a story. You know that the bomb will either explode, or they will disable it in the nick of time. But that tension you feel is what makes the movie engaging.

When you plant details in your story for your readers, you are building tension. To return to our earlier example of the armchair, your reader will continue to wonder what the armchair means as the story goes on. By the end of your story, your reader has picked up on several details, and they are filled with anticipation.

How Do I Use Chekhov’s Gun in My Story?

Chekhov’s gun is not a rhetorical device like a red herring or a metaphor. It is a principle related to plot development.

When you are planning your novel, consider the details you want to include and when you want to include them. It might be helpful to work backward from the payoff to find where to plant your details.

It’s easy to add details when you’re in the flow of writing, only for them never to be mentioned again. You might think it has significance at the time of writing, but later it just doesn’t work. That’s okay.

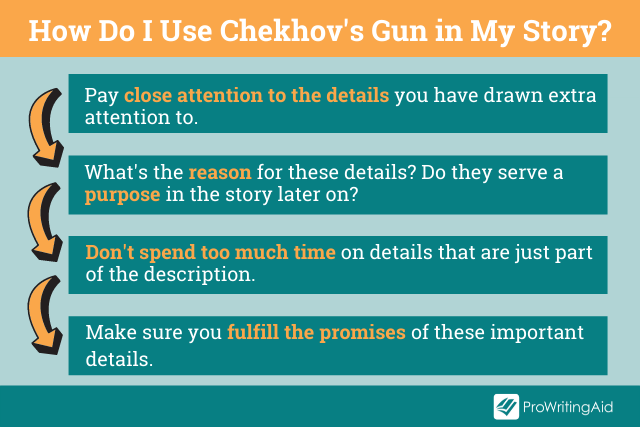

I find it easiest to look at Chekhov’s gun during the developmental or content editing stages of the writing process. Pay close attention to the details you have drawn extra attention to. Ask what the purpose of those details are. Are they only there for setting or sensory descriptions? Or do they serve a purpose to the narrative later on?

Download and keep our free guide to every stage of the editing process.

If these details are just part of your description, and they are normal or inconsequential details (e.g. a rainy day in Scotland is not significant, but a month of no rain would be strange), make sure you don’t spend too much time on them. But if they have a payoff later on, elaborate to draw attention to them.

Finally, make sure you fulfill the promises of these important details. Find where each of these details make their payoff. Add it if you can't find it. Ask yourself if it is a satisfying resolution.

What Are Some Examples of Chekhov’s Gun?

Here are some great examples of Chekhov’s gun:

- In The Dresden Files: Fool Moon, Harry Dresden’s pentacle necklace that was given to him by his mother is later used to kill the loup-garou as a makeshift bullet.

- In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Arthur kills a fly and mentions eating oysters near the beginning. Later we discover that these are two manifestations of Agrajag, and Arthur has killed every reincarnation of it.

- In Ready Player One, Wade wins a quarter from a perfect game of Pac-Man. He forgets about it until much later when he is killed. The quarter is an extra life, so he survives permanent death.

- In A Song of Ice and Fire, Daenerys receives three dragon eggs as a wedding gift. They are supposed to be fossils. Later, they hatch in Khal Drogo’s funeral pyre, and Daenerys becomes the Mother of Dragons.

- In The Lord of the Rings, the hobbits receive enchanted daggers at the beginning of their adventure. Much later, at the battle of Minas Tirith, Merry stabs the Witch-King of Angmar, which enables Eowyn to take the wraith down. The enchanted part of the dagger was that is was able to take down enemies of Angmar.

There are plenty of other examples of Chekhov’s gun in literature, film, and TV. See if you can recognize some the next time you’re engaging with a work of art.

And, now that you’ve learned so much about what Chekhov’s gun is and how to use it, see if you can employ this principle the next time you work on a story.