Every great storyteller needs to understand how to develop characters.

Think about your favorite stories—the ones that stuck with you even after you turned the last page. What was the magic that made those stories so compelling?

Most likely, the answer has something to do with good character development. It doesn’t matter how intricate your worldbuilding is, or even how exciting your plot is. If your characters fall flat, your readers will probably stop reading.

What Is Character Development?

Character development is how you create your characters both on and off the page. Within your story, your characters will change as they move through your plot. Good character development shows your reader this change gradually through your characters’ actions, decisions, and reactions.

But before you can create convincing characters for your reader, you need to plot their development off the page, too.

This article will teach you how to build three-dimensional characters from the inside out. Read on to learn how to create fictional characters that will capture readers’ hearts and bring your stories to life.

Internal Characteristics: Wants, Needs, and Flaws

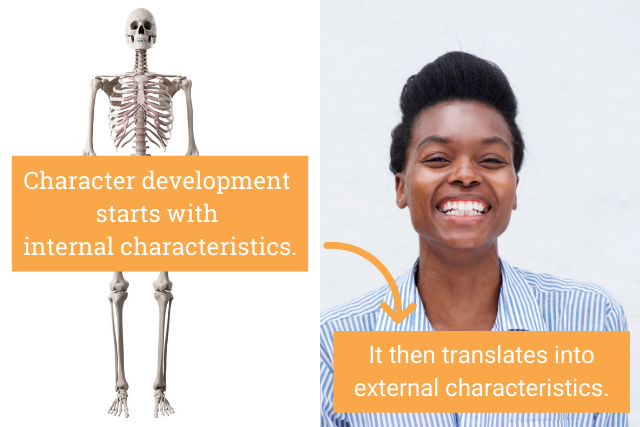

The best character development starts from within.

We’ll start by fleshing out your main character’s internal characteristics: the motivations, emotions, fears, and flaws that drive them to behave the way they do.

What Does Your Main Character Want—and Why?

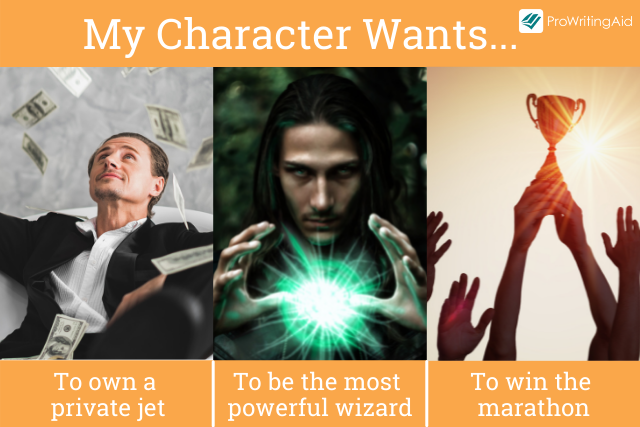

The first step in developing compelling characters is to figure out what each character wants most in the world. This is most important with your protagonist and antagonist, but it can be helpful for secondary characters, too.

Try to be as specific as you can when answering this question. A vague answer (e.g. “My character wants to be popular”) is less useful than a specific answer (e.g. “My character wants to be elected homecoming queen”).

Answering this question well doesn’t just help you develop your story’s characters—it also helps you develop your story’s plot. After all, the plot is what happens when something gets in the way of what your characters want. Once you figure out what the main character wants and what obstacles are preventing them from getting it, the rest of the story will follow.

Here are three examples of well-developed main characters and what they want most at the beginning of the story:

In A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, Scrooge wants to keep all his hard-earned riches for himself. Even when people around him are shivering in abject poverty, he refuses to share any of it with them.

In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, Katniss wants to keep herself and her family alive at all costs. Even when she sees horrible injustices happening in District 12, she never takes a stand, because it would put herself and her family in danger.

In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, Dorothy wants to live somewhere less boring than her aunt and uncle’s little house in Kansas. Even though she has a loving family, she yearns for an opportunity to be somewhere more exciting.

Ask yourself:

What’s the one thing your character wants more than anything in the world—the one thing that they think will finally make them feel happy and fulfilled?

Why does your character want this so much? What will getting this mean to them?

What’s preventing them from getting what they want? What obstacles are standing in their way?

What Does Your Main Character Need—and Why?

At first glance, this might seem similar to the previous question, but in reality, what you want and what you need can be two very different things.

What your character wants is a surface-level desire that they think will make them happy. What they need, however, is the thing they actually require in order to achieve true happiness, even if they don’t know it yet.

This battle between “want” and “need” will create an endless well of internal conflicts and tension. This creates a great overall character arc and avoids a boring and static character.

Again, try to be specific here. A vague answer (e.g. “My character needs friendship”) is less useful than a specific answer (e.g. “My character needs true friends who love her for who she really is, not false friends who don’t let her be herself”).

Here are some examples from the same stories we discussed earlier:

In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge wants to keep all his hard-earned riches for himself, but this just makes him lonely and miserable. What he really needs is to share his wealth with those less fortunate. Once he begins acting out of compassion instead of greed, he feels more happiness than he ever did when he was holding on to his mountains of wealth.

In The Hunger Games, Katniss wants to keep herself and her family alive at all costs, but this just makes her cynical and afraid. What she really needs is to be willing to risk her life to fight for what she believes in. Once she begins acting as a symbol for the rebellion, she finds that her life has finally gained meaning.

In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Dorothy wants to live somewhere less boring than her aunt and uncle’s little house in Kansas, but this just makes her dissatisfied and ungrateful. What she really needs is to learn that “there’s no place like home.” Once she finally makes her way home again, she feels more contentment than she ever did in the exciting land of Oz.

Ask yourself:

What does your character truly need to feel happy and whole?

Are they aware of this need? If so, what’s preventing them from achieving it?

Can they have what they want and what they need at the same time? If not, which one will they choose at the end of the story?

What Are Your Character’s Flaws?

Now that you know what your character wants and what your character needs, it’s time to flesh out their flaws.

It’s a common mistake to think that a perfect protagonist is the same thing as a likable protagonist. In truth, readers relate more to characters with flaws than to characters that are too perfect.

We’re not talking about surface-level flaws here, like frizzy hair or mild clumsiness—we’re talking about real, human flaws that cause your character to hurt themselves or those they care about. If you don’t give your character any flaws, you also don’t give them any room for growth.

In some cases, the difference between what your character wants and what your character needs might directly imply a character flaw. For example, Scrooge’s greatest flaw is his miserliness. This is closely related to what he wants most in the world—to keep his mountains of money to himself.

In other cases, you’ll need to dig a little harder to come up with your character's flaws. If you’re stuck, remember that a strength can often become a flaw if taken to extremes.

For example, if your character’s greatest strength is their compassion, their greatest flaw might be that they let others take advantage of them. Or if their greatest strength is their independence, their greatest flaw might be that they struggle to accept help when they need it.

Ask yourself:

Does the difference between what your character wants and what your character needs imply an obvious character flaw?

What are your character’s strengths? Do any of those strengths become a flaw when taken to extremes?

In what ways does your character tend to cause harm to people they care about? Why?

What’s Your Character’s Backstory?

Once you know what your character wants, what your character needs, and what their major flaws are, it’s time to figure out why they are the way that they are.

The most memorable characters are the ones who do bad things for good reasons. For example, Scrooge is miserly and stingy with his money because he grew up in poverty and pulled himself up by his bootstraps. Katniss is pragmatic and focused on survival because her father died when she was a child, leaving her as the one responsible for keeping her family alive.

A compelling backstory will make your readers empathize with your characters, regardless of how many mistakes they make, because they understand why your characters would act this way.

Ask yourself:

Was there a specific moment when your character first started desiring the thing they want more than anything? What was it?

What caused your character’s main flaw? Did this flaw protect them from something?

Who hurt your character in the past? What traumas have they survived?

Write a Satisfying Character Arc

In the previous question, we looked to your character’s past to figure out what happened to them before the story started. Now it’s time to look forward.

Good stories transform your characters. The plot should force all of your main characters to change in some fundamental way.

This is what’s commonly referred to as a “character arc.” Your character can have a positive character arc (e.g. cowardly to brave). Or, less commonly, they can have a negative character arc (e.g. naïve to cynical).

The best character arcs are the ones that center around what your character wants and what your character needs. Around three-quarters of the way through the story, your protagonist should realize that they’ve been chasing the wrong thing. Their motivations change and, at last, they begin pursuing what they truly need, instead of what they thought they wanted.

Ask yourself:

How will the plot force your character to confront their flaws?

How will the plot force your character to choose between getting what they want and getting what they need?

What fundamental lesson will your character have learned by the end of the story?

External Characteristics: Looks, Voice, and Personality

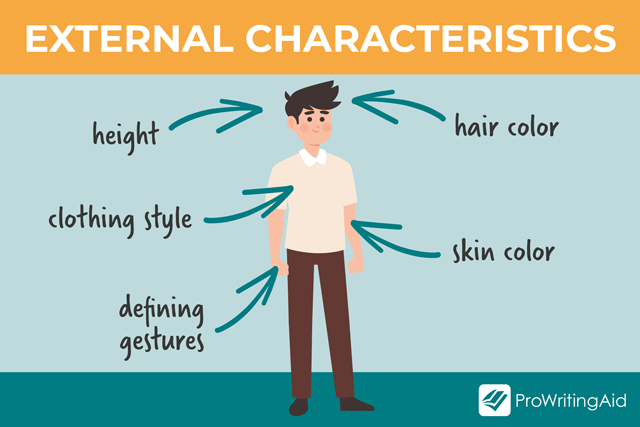

External characteristics encompass all of your character’s more physical traits: what they look like, what they sound like, and how they present themselves to the world.

Here’s the good news: if you’ve already fleshed out your character’s internal characteristics, you’ve got the skeleton down already. Now you just need to add flesh to the bones by working your way out from what you’ve already established.

What Does Your Character Look Like?

Start with the internal characteristics you’ve figured out. It doesn’t matter so much whether your character’s eyes are blue or brown if that’s not important to the story. What will matter to your readers are the aspects of the character’s appearance that reinforce their internal characteristics.

Here are some well-developed character examples in literature. Notice that these authors include specific details that tell us something about what kind of person the character is on the inside, as well as on the outside.

“Fifteen-year-old Jo was very tall, thin, and brown, and reminded one of a colt, for she never seemed to know what to do with her long limbs, which were very much in her way. She had a decided mouth, a comical nose, and sharp, gray eyes, which appeared to see everything, and were by turns fierce, funny, or thoughtful. Her long, thick hair was her one beauty, but it was usually bundled into a net, to be out of her way. Round shoulders had Jo, big hands and feet, a flyaway look to her clothes, and the uncomfortable appearance of a girl who was rapidly shooting up into a woman and didn't like it.”

—Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

“Her skin was a rich black that would have peeled like a plum if snagged, but then no one would have thought of getting close enough to Mrs. Flowers to ruffle her dress, let alone snag her skin. She didn’t encourage familiarity. She wore gloves too. I don’t think I ever saw Mrs. Flowers laugh, but she smiled often. A slow widening of her thin black lips to show even, small white teeth, then the slow effortless closing. When she chose to smile on me, I always wanted to thank her.”

—I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

“Ender did not see Peter as the beautiful ten-year-old boy that grown-ups saw, with dark, tousled hair and a face that could have belonged to Alexander the Great. Ender looked at Peter only to detect anger or boredom, the dangerous moods that almost always led to pain.”

—Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card

Ask yourself:

What external traits does your character have that shed insight on their internal characteristics?

How much does your character care about their appearance? How long do they spend getting ready in the morning?

Do they have any defining gestures (e.g. biting their nails when they’re nervous)?

What Does Your Character Sound Like?

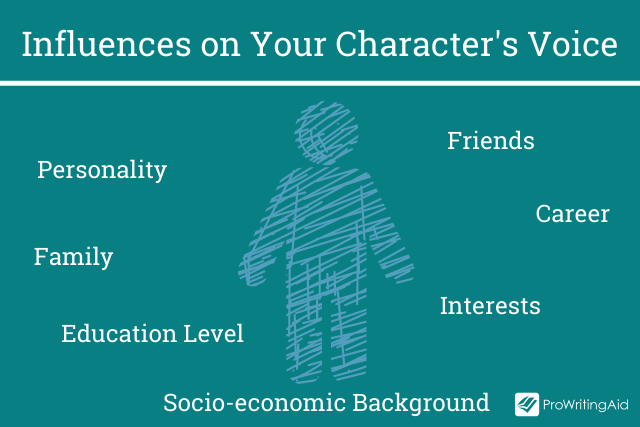

Many writers like to start a new story by figuring out their characters’ voices. After all, physical descriptions tend to be relatively brief, but dialogue can go on for pages at a time.

No two characters sound exactly the same. Some are soft-spoken, while others are loud and confident. Some crack jokes, while others stay serious even in the most absurd situations.

If you can give your character a unique and consistent voice, they’ll feel more three-dimensional and alive.

Ask yourself:

What’s your character’s personality like, and how does this affect the way they speak? (e.g. extroversion/introversion, sense of humor)

What’s your character’s education level and socioeconomic background, and how does this affect the way they speak? (e.g. slang, obscure vocabulary words)

What’s your character’s career? How does this affect the way they speak? (e.g. industry-specific references/terminology)

What Are Your Character’s Interests and Hobbies?

It’s easiest for readers to relate to characters who have passions.

Again, try to be specific here. If you’ve decided that your character likes art, try to take it one step further: what mediums do they use? What period of art history are they most obsessed by?

Ask yourself:

What does your character do in their spare time?

What personal items matter the most to your character? (e.g. art supplies, running shoes)

What could your character talk about for an hour without prepping beforehand?

Surprise Your Reader

What’s Contradictory or Unexpected About Your Character?

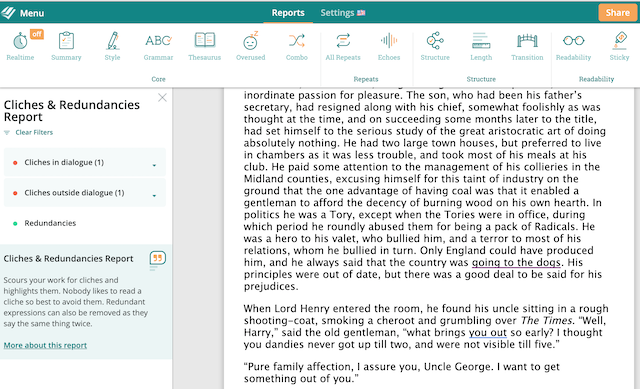

We’re all familiar with most character tropes out there: the popular mean girls, for example, or the world-weary detectives. These tropes can be a useful part of your toolkit, but if you rely on them too much, they can also make your story boring and forgettable. You can rely on ProWritingAid’s cliché report to help you avoid these sneaky tropes and keep your writing exciting.

Instead of using clichés, it’s time to figure out what’s contradictory or unexpected about your characters. For example, if they’re a particularly cynical character, consider giving them a specific cause that they’re surprisingly idealistic about. Or, if they’re a particularly silly character, consider giving them a specific topic that they’d never joke about.

Ask yourself:

What do your character’s close friends know about them that nobody else knows?

Does your character behave differently around some people than around others? Why?

Does your character resemble a common character trope? If so, how do they subvert that trope?

Fun Character Development Writing Exercises

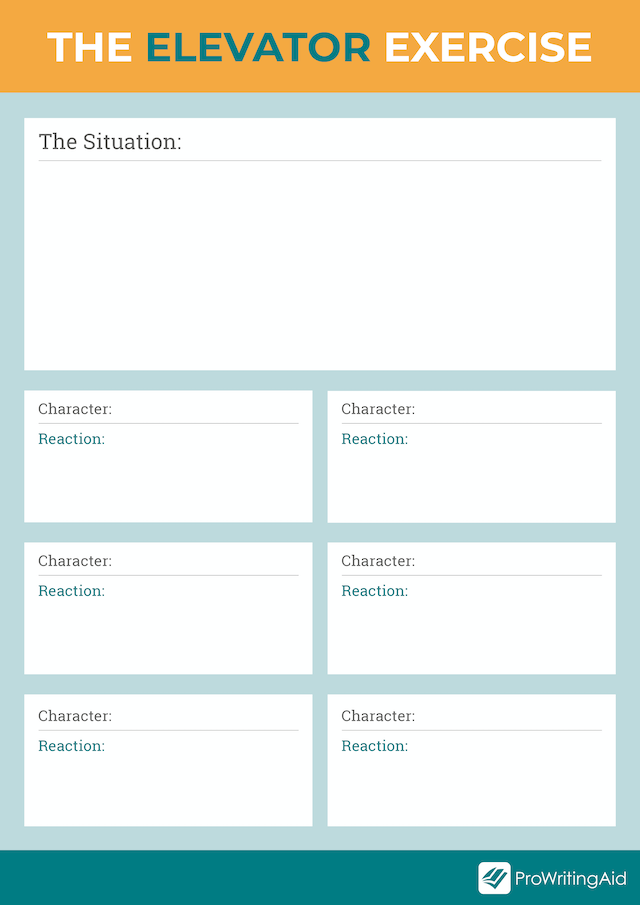

The Elevator Exercise

Imagine that all of your main characters are riding together in an elevator. Then, imagine that the elevator malfunctions.

Take out your laptop or a notebook and write out the scene and think about how each character responds.

Which characters panic? Which characters stay calm? Which characters take the lead and try to control the room? Which other characters start cracking jokes?

Download the Elevator Exercise Worksheet here

You can tweak the parameters of this exercise, depending on what kind of story you’re writing. If you’re writing a steamy romance, you can replace the malfunctioning elevator with a locked bedroom. If you’re writing a space opera, you can replace the malfunctioning elevator with a crashing spaceship. The goal is to find out how your characters react under pressure, and what that says about who they are.

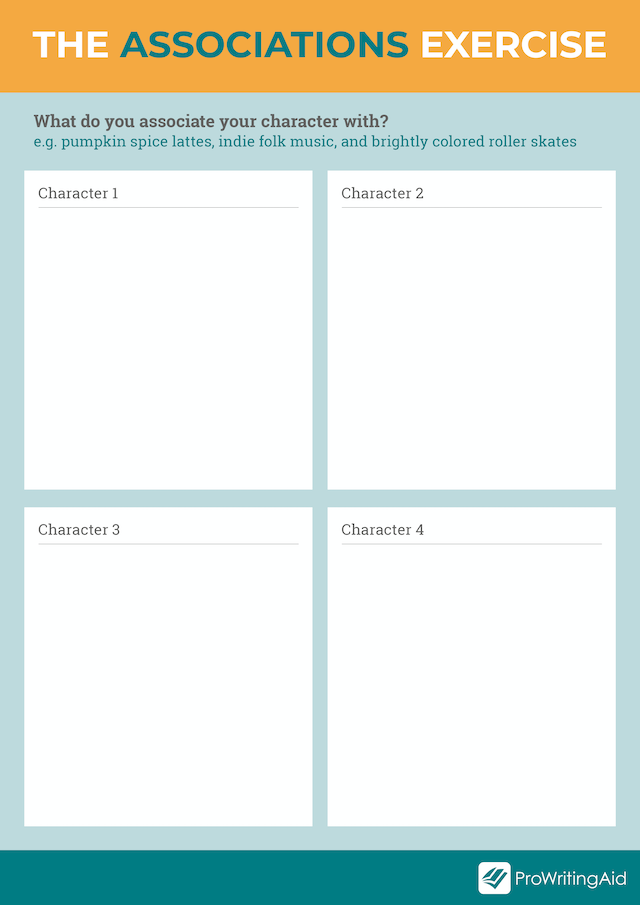

The Associations Exercise

If you’re a more atmospheric writer and you tend to write based on your gut, this one is a useful exercise for you.

The concept is simple: make a list of all the things you associate your character with. For example, one of my characters makes me think of pumpkin spice lattes, indie folk music, and brightly colored roller skates. Another one of my characters makes me think of drunken bar brawls, three-in-one shampoo, and geraniums.

Download the Associations Exercise Worksheet here

As you’re drafting your story, you can refer back to this list whenever you feel like you’re losing sight of who your character is supposed to be.

Read, Read, Read

One of the most effective ways to grow as a writer is to read. Read stories like the ones you want to write, and stories unlike them. Read in every genre and time period, even the ones you don’t normally enjoy.

And I’m talking about active reading, not just passive reading. Think of a chess player studying the strategies of the greatest grandmasters, or a football player studying the moves made by their favorite athletes.

Pay attention to your favorite characters and what makes them memorable. Over time, you’ll collect more reference points for your own characters.

Conclusion

Now you’re ready to write a story with compelling, multi-dimensional characters. By starting from within and working your way out, you can create characters worthy of driving your stories.