Do your students struggle with the fear of a blank page? Or maybe they tell you they just can’t think of anything to write about?

We can’t expect our students to think of great ideas without some support. That’s where modeled writing comes in. It’s a chance to demonstrate and co-create a high-quality example of the work you want to see.

Here’s six ideas to embed modeled writing in your classroom.

1: Experience Great Published Literature

How can your students be good writers if they don’t have experience of what good writing looks like?

Make reading a central part of English lessons. Share book reviews, tell your students about newly published stories, and take them for reading sessions in your library.

Show them you’re a reader too. Always have a book on the go at school. Put what you're reading on your email signature and display it on your door for all to see.

At first your class will copy these stories in their writing. You'll recognize familiar events and characters from books you've shared together. This is an essential part of learning to write.

2: Learn Oral Versions of Stories

Go beyond simply reading stories to the class. Make it an experience they actively participate in.

Literacy expert, Pie Corbett, developed a method called Talk For Writing. Children internalize writing patterns and familiar structures using role play, actions, and repetition. You can hear Pie talking about his approach on this video.

3: Share Good Examples

Create an example of ‘What A Good One Looks Like’ (WAGOLL) or find one online for the genre you’re teaching. Sharing an example lets your students understand the features you expect them to include.

Talk about what makes it great. Highlight vocabulary and sentence structures. Unpick it to learn the craft of the author.

Mark the WAGOLL with the students against your success criteria. This will let them see areas of strength and where improvements could still be made.

4: Edit Extracts of Published Work

If you want your students to create a specific piece, find a published example and use it as your base. Think of the opening of To Kill a Mockingbird for an atmospheric setting description, or Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone for the vivid character descriptions of the Dursley family.

Before they can innovate, they need to emulate. Start simple, literally cutting out words to replace with their own choices.

Here’s my example using Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird as the basis of a description for a different location.

Original text

Maycomb was an old town, but it was a tired old town when I first knew it. In rainy weather the streets turned to red slop; grass grew on the sidewalks, the courthouse sagged in the square.

Altered version

Chester was a sprawling town, but it was an exciting town when I first knew it. In good weather the streets were filled with hopeful families, looking for the best spots for a picnic lunch; trees provided much-needed shade, the shops bustled with spending.

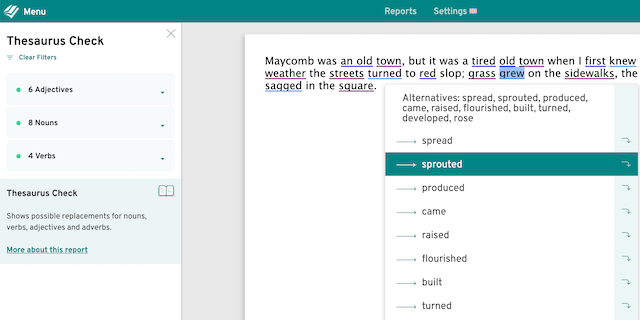

If you want to help your students visualize the editing process, use ProWritingAid. The Thesaurus Report will highlight words that have interesting synonyms.

Just open a blank document in ProWritingAid, and paste your extract in. You can talk through the different synonyms the software suggests and whether they fit with what the author is trying to say. Picking the best synonym together shows your learners that the first word that comes to mind isn't always the best choice.

Don’t think of emulation as cheating. It’s providing students with the support they need until they produce their own ideas. Using extracts from published texts gives students exposure to the quality of writing you want them to produce themselves. Before long, they’ll move beyond this structure and begin to show originality.

5: I Do—We Do—You Do

Don’t just send your students off to start writing—they’ll flounder.

Instead, let them first see you having a try (‘I Do’). Narrate your thought process, like you’ve added audio description to your actions. They can see you make mistakes, change your mind, and improve ideas.

Now create a shared version (‘We Do’). Ask them to contribute ideas. Use mini-whiteboards to draft sentences. Add in voting and debates to make it fun. Let them see this is a collaborative piece. Create an excellent example together.

Only then is it time for them to write by themselves (‘You Do’). Less confident learners will stick closely to your shared version and imitate it, as I did with To Kill a Mockingbird. As they become more confident, they’ll move away from this supportive framework and start creating something original.

6: Use Support Structures

When your students write independently, you can still give scaffolded supports. It’s hard for them to just start writing. Providing prompts will help overcome their worries and let their creativity out.

Try these supports:

- Sentence starters

- Prompt questions

- Cartoon strips

- Writing arcs / story mountains

- Word banks

- Multiple choice options

There are plenty of writing frames available online or try making your own with a simple free graphics program like Visme.

Final Thoughts

It’s easy to forget that our learners haven’t read as broadly as we have. They can’t write what they haven’t experienced. Building reading into the curriculum lets them explore and emulate, leading to truly original compositions of their own.

Your students aren’t mind readers. Dedicating time to collaborative drafting gives them an idea of what you’re expecting. It brings your list of success criteria to life by showing them what success looks like.

Modeled writing is often squeezed out by the rush to get on with independent writing. This has a significant impact on the quality you’re likely to get. Make time for this crucial step in your teaching sequence. You won’t regret it.