Many fiction writers learn how to tell stories by watching movies.

You can master some fantastic storytelling techniques that way. At the same time, though, there are some bad habits you might pick up from films that don’t translate well to prose.

So, what do you need to know if you’re a fiction writer who loves films?

In this article, we break down five things you can learn about writing by watching movies—and five things you can’t.

Should Fiction Writers Study Movies?

If you want to create great stories, you need to start by consuming great stories.

Luckily, it doesn’t really matter what form those stories come in. Whether you prefer to sit in the movie theater with a bucket of popcorn or curl up in your bed with a good book, you’re still feeding your imagination and refilling your creative well.

As a fiction writer, you can study movies the same way you might study novels and short stories.

When you encounter something you admire in a movie, something that makes you think “Wow, I wish I’d thought of that,” try to figure out how the director achieved that effect. Ask yourself, “How could I achieve that same effect in my own stories?”

When you encounter something that bothers you in a movie, ask yourself, “How would I have done it differently if I were telling the story?”

Thinking critically about the stories you consume, both on the page and on the screen, will expedite your growth as a writer and storyteller.

Five Things You Can Learn From Movies

Without further ado, here are five storytelling techniques you can learn from watching movies.

1. How to Craft Strong Dialogue

Screenwriters are masters at writing dialogue.

It can be useful to study the conversations characters have with one another in great films. Here are three questions you can ask yourself about movie conversations:

- Question 1: What did the characters say out loud, and what does that tell me about who they are?

Movies and shows are great at using dialogue to establish character. You can almost always tell who’s talking without even seeing them on screen. Characters with different backgrounds and personalities use different word choices, sentence lengths, and even turns of phrase.

- Question 2: What did the characters leave unsaid, and how does that create a deeper layer of meaning underneath the surface?

Many screenwriters use subtext to convey something deeper—the actual dialogue is just the tip of the iceberg.

For example, if one character has a crush on another character, or if one character is angry with another character, you might infer these relationship dynamics from their conversations, even if they never say how they’re feeling.

- Question 3: What purpose does this conversation serve in the story?

Every dialogue scene should serve a clear purpose. For example, it might drive the plot forward, establish character growth, give the audience important information, or sometimes even all three.

Asking these three questions when you’re watching movies can help you strengthen the dialogue in your own writing.

2. How to Structure a Tight Plot

Movies tend to follow very tight plot structures.

The average novel is 80,000 words long, while the average screenplay is only 7,500–20,000 words long. Novels have more room to meander, while movies need to hit the right story beats at the right times in order to keep the viewer’s interest.

As a result, screenwriters often use beat sheets, which are outlines that dictate when each story beat should occur, to structure their plots.

Many beat sheets that were originally created for movies, such as Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat!, have become extremely popular among novelists.

Whenever you watch a great movie, pay attention to the key turning points in the plot and the time stamps at which they occur. For example:

- When does the inciting incident occur?

- Is there a change in the main character’s overarching goal, and if so, when?

- Do the stakes get raised for the main character, and if so, when?

- When does the main character hit their lowest point?

- When does the main character have their final climactic confrontation with the antagonist?

Of course, you don’t necessarily need to stick to a traditional plot structure in your novel. And if you’re writing a character-driven or even vibe-driven novel, plotting might not be a top priority for you.

If you do want to follow a traditional plot structure, though, watching movies is one of the best ways to start.

3. How to Create a Cinematic World

Cinematographers do a fantastic job creating immersive, eye-catching settings.

Think of Studio Ghibli’s magical, gorgeous worlds in movies such as Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro.

Or think of Tim Burton’s creepy, whimsical worlds in movies such as The Nightmare Before Christmas and Alice in Wonderland.

Setting is a crucial component of fiction writing, and it’s one that’s easy to forget about if you’re focusing on character and plot.

If you’re trying to get better at writing settings, watching cinematic movies is a great way to create visually arresting worlds.

4. How to Use Characters’ Body Language

Actors excel at using body language to reveal character and emotion.

For example, a shy character might glance at the clock when she’s impatient, fiddle with her necklace when she’s nervous, or leave the room when she’s angry.

In contrast, an aggressive character might tap her foot when she’s impatient, pace around the room when she’s nervous, or punch a wall when she’s angry.

If you’re looking for action beats to use in your own story, you can start by watching movies with characters similar to your character and paying attention to their body language.

5. How to Master Blocking

Blocking means describing where characters are at any given moment and how they’re moving. You can think of blocking as similar to stage directions, such as “Character A enters from the right,” or “Character B sits down at the table.”

Let’s say you want to write a fight scene. Or a dancing scene. Or a soccer game. Blocking will be absolutely crucial.

It can be hard to keep track of where all your characters are at any given moment. Many fiction writers struggle with blocking in scenes where multiple characters are moving around at once.

For example, you might accidentally write about a character getting up from the living room couch, when the reader thought that character was still cooking in the kitchen.

Watching movies with those types of scenes can be a great way to figure out how to block them correctly.

Five Risks of Learning From Movies

There are also some downsides to studying movies. After all, there are things you can do with a pen and paper that you can’t do with a camera, and vice versa.

Here are five bad habits writers tend to pick up from movies and TV.

1. Ignoring Your Protagonist’s Internal World

The unique magic of books is that they can put you directly into a character’s head.

A great writer can show the reader everything a character is thinking and feeling. For example, you can include lines like, “She wondered what was in the box,” or “He wished his mother would stop nagging him.”

Movies don’t have that ability. Some movies include a voice-over narrator who tries to accomplish the same thing as narration in a novel, but it often feels less organic and more heavy handed than it does in a book.

Most of the time, screenwriters show you what a character is thinking and feeling through externals—a character might clench their fists when they’re angry, lie down in an empty field when they’re lonely, or make sarcastic quips when they’re annoyed.

One common mistake that fiction writers make is trying to do that exact same thing—to show the hero externally instead of internally.

For example, when I was first starting out as a writer, I often wrote scenes where my protagonist would react to something with a surprised expression.

The problem with that approach is that I was taking the reader out of the protagonist’s head. Instead of showing the protagonist’s face, it would have been much more effective to show us what was happening inside their head.

Here’s a quick example:

- External (better for movies): “Sadie turned around to look at the man behind her. Her jaw dropped in surprise when she saw him.”

- Internal (better for books): “Sadie turned around. The man behind her looked exactly like Shawn. For a moment, she felt like someone had knocked all the air out of her. But it couldn’t be Shawn—Shawn was dead.”

2. Showing Scenes That Don’t Need to Be Shown

“Show, don’t tell” is an important rule for new writers, but it shouldn’t be followed all the time.

It’s important to strike the right balance between telling and showing in your fiction. Knowing when to show and when to tell is a great technique for controlling pacing.

Sometimes, you want to immerse the reader in every moment of a scene, such as when your character’s going through a big, emotional breakup. Other times, you just want to summarize what’s happening, such as when your character’s driving to work in the morning.

In movies, almost everything is shown. You might see short montages of characters driving from one place to another or of characters getting ready in the morning.

One common mistake writers make is to show things that don’t need to be shown because that’s what a movie would do. For example, transition scenes that get your characters from point A to point B—whether it’s a drive, a train ride, or a journey on horseback—are often unimportant to the story.

Don’t be afraid to simply tell the reader, “They took a train to London,” or “They arrived three hours later,” instead of describing the journey. Summarizing like this is hard for movies to do but is perfectly acceptable—and often even necessary—for fiction writers.

3. Relying on Sight and Sound

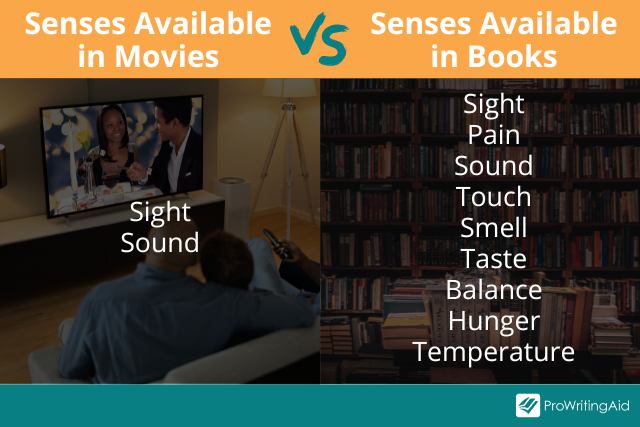

Movies and TV shows have two sensory tools at their disposal: sight and sound.

We don’t yet have the technology to include “smelltracks” and “tastetracks” in films, but luckily, we can do that—and more—in novels and short stories.

Also, don’t underestimate the power of touch. Think about what your characters are touching—their textures, temperatures, and any other relevant qualities—and communicate that to the reader.

When I write scenes, I often focus a lot on what my protagonist is seeing and hearing, but not so much on the other senses. When it’s time for revision, one thing I always have to do is go back through my book and add in other sensory details.

4. Describing Too Many Facial Expressions

If you’ve noticed that your writing includes an overabundance of words like “smiled,” “scowled,” or “furrowed her brow,” you might be relying too much on facial expressions.

Most movies include closeup shots of characters’ faces to help you see what they’re thinking and feeling. Movies have to use these tools because, like we mentioned before, they can’t put you directly into the hero’s head.

When you’re writing a book or short story, you don’t have to show a close angle of your characters’ faces all the time. Let them use their whole bodies to express themselves—or if they’re a POV character, let them tell us directly what they’re thinking and feeling.

5. Thinking Inside the Box

Most movie makers have to factor in production constraints.

What props do they have? What shooting locations do they have? How big is their budget? That’s the “box.” If they think outside the box, the movie can’t get made.

For example, most movies before CGI made humanoid versions of aliens and monsters because it was easier to dress up a human actor than to create an animatronic.

As a writer, on the other hand, you have access to any aliens and monsters you can possibly imagine. The same goes for otherworldly settings, impossible props, and even out-of-the-box POVs.

You can write a story from the viewpoint of a living planet, or invent a species that has no visible form at all. Written stories let you think outside the box without getting a producer’s approval first.

Conclusion on How Fiction Writers Can Learn From Movies

There you have it—the top five ways fiction writers can learn from movies and TV, and five ways they can’t.

What are some movies and TV shows you love? Let us know in the comments!