Logical fallacies are arguments that can’t stand up to critical thinking. There’s a defect in their reasoning that renders their conclusions invalid—not credible.

Imagine a political sign that says:

- Don’t elect Meg Jones for mayor. She went to a second-rate college!

Or listening to your anxious teen fret about an upcoming road test:

- If I don’t pass my driving test, I won't be able to get to a job. I’ll never make any money or be able to take care of myself and will have absolutely no future.

Or an ad campaign for an organic food company that says:

- You let your kids eat non-organic food? You might as well let them smoke cigarettes.

What do you think? Do the arguments presented stand up to reason?

They may have gotten your attention but, ultimately, each is a distraction, over-reaction, or misdirection, not a logical argument.

What Is a Logical Fallacy?

Solid arguments are based on evidence and reason. Their power to convince exists because they are built on logic and supported by honest thinking, relevant facts, evidence, and/or examples. Solid arguments can stand up to scrutiny.

Logical fallacies are defective, even dishonorable, arguments.

They are based on a faulty and unreasonable sense of logic or manipulated evidence, though they are often presented with energy and conviction.

Take the examples from the opening:

- Don’t elect Meg Jones for mayor. She went to a second-rate college!

Rather than provide a legitimate reason why Meg Jones isn’t a good choice for mayor, the sign throws a cheap shot insulting her education. Whether her college of choice was “second-rate” or not, that detail isn’t relevant to her mayoral policies.

- If I don’t pass my driving test, I won't be able to get to a job. I’ll never make any money or be able to take care of myself and will have absolutely no future.

The hopeful teenaged driver lets panic overtake reason, arguing that the driving test results will determine all future success or failure in their life.

This far-fetched outcome is easily dismantled with some perspective: If you fail the test, you take it again. Even if you never pass the test (which is unlikely), you can use public transportation!

- You let your kids eat non-organic food? You might as well let them smoke cigarettes.

The organic food ad argues that eating non-organic food is on the same level as smoking. While organic food may be a healthier option, to compare consuming inorganic food to inhaling dangerous carcinogens is an irresponsible reach. Are as many people facing health consequences from consuming inorganic food as there are facing health consequences of smoking?

Why Do People Use Logical Fallacies?

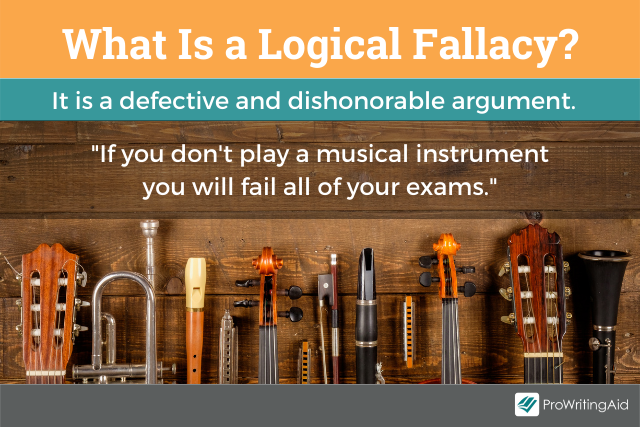

Logical fallacies are an easy way to strike a blow at an opponent or an opposing idea.

Their bold, distracting arguments can work! Logical fallacies are popular in politics and advertising, but also appear in our personal conversations, as the frantic teenage driver-to-be reminds us.

Logical fallacies can also be used as a source of humor. When the deliverer of the argument knows it’s ridiculous, the effect can be entertaining.

While using logical fallacies intentionally as comedy is fine—no one is trying to deceive or mislead the audience who is “in on the joke”—using them intentionally to distract or mislead is irresponsible and dishonest.

Including logical fallacies in your arguments accidentally is also problematic.

Whether intentional or accidental, using logical fallacies ultimately damages your credibility.

If intentional, they indicate you don’t have substantive arguments to offer and that you are willing to resort to manipulative techniques.

If accidental, their presence indicates that you lack critical thinking skills and cannot recognize the weaknesses in your own arguments.

Why Recognizing Logical Fallacies Is Important

Being able to recognize common logical fallacies in your own arguments gives you the opportunity to change course before you damage your credibility.

When you recognize logical fallacies in others’ arguments, you prevent yourself from being misled.

This list of ten common logical fallacies will help you get your critical thinking radar up, so you can avoid offering or falling for logical fallacies.

10 Common Logical Fallacies and Examples

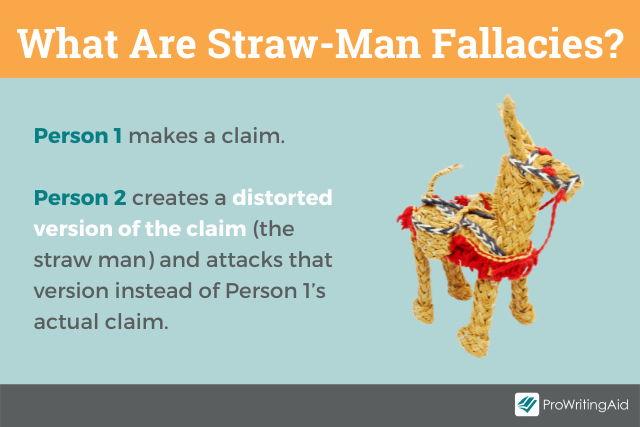

1. The Straw Man Argument

Straw man fallacies distort a person’s argument and attack that distortion in order to distract from the actual issue at hand. They work like this:

- Person 1 makes a claim

- Person 2 creates a distorted version of the claim (this is the straw man) and then attacks that distorted version as a way of seemingly attacking Person 1’s initial claim.

For example:

- Person 1: I think I’d rather have a burger than lo mein for lunch.

- Person 2: Why do you hate Chinese food? I guess you just don’t appreciate food from Asian cultures.

That’s a rather minor example, but the straw man fallacy is popular among politicians where bigger stakes are at play.

For example:

- Politician 1: It would be irresponsible for me to vote to increase the military budget when we are facing such a national financial crisis.

- Politician 2: I guess you don’t care about our military then—nor do you care about our national safety.

The name “straw man” refers to the weakness of the distorted argument; it has as much power to stand as a bundle of straw, or a scarecrow, does.

That straw man’s purpose is to distract; now, the person who created the straw man fights that weakened distortion, instead of the actual argument.

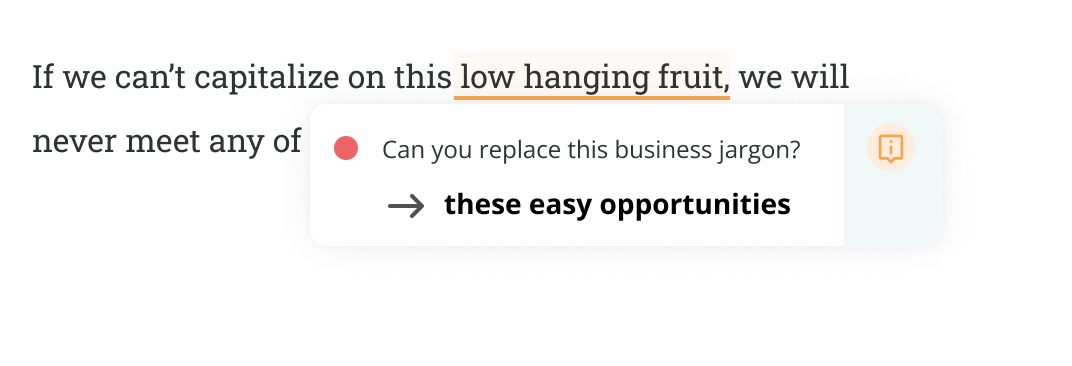

Logical fallacies weaken you arguments, but there are other indicators that could show your points are unfounded.

Great writing conveys ideas clearly. When you use business jargon, you dilute your meaning with phrases that have become empty and dull through overuse.

ProWritingAid checks your writing for jargon so you can make sure you're communicating clearly.

If you find that you can't think of another way to phrase your sentence, think about whether you need it at all, or if—like logical fallacies—it's just a distraction.

Check your writing for free with a ProWritingAid account.

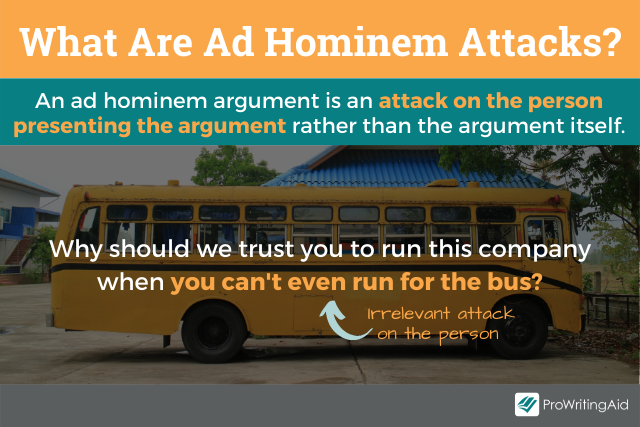

2. The Ad Hominem Attack

Ad hominem means “against the man.”

An ad hominem argument is an attack on the person presenting the argument rather than the argument itself.

While the personal attack may be true, it’s irrelevant to the argument—and is often just plain rude.

For example:

Politician 1: I will review the budget carefully, getting rid of any special interest projects we are paying for as “favors.”

Politician 2: You can’t even work out your divorce settlement! Why should anyone trust you with a budget?

This example is like the accusation that mayoral candidate Meg Jones went to a second-rate college. The insult has no bearing on the issue at hand and is simply a deflection.

The tu quoque fallacy is a popular form of the ad hominem attack and shows how a true statement is not always a substantial argument.

The tu quoque fallacy is an appeal to hypocrisy, or a “you too!” argument.

Let’s say a dad catches his teenager smoking. The dad is a smoker himself, so the teen says, “how can you tell me not to smoke when you do it?”

The teen is right that the dad is a smoker, but that doesn’t mean the teen should take up the habit, and his (or her) argument can be rather easily dismantled.

The dad can acknowledge that he is a smoker, and because of what he’s experienced from the habit, wants to protect the teen from similar consequences.

However, sometimes the “you too” argument can be used as a “call out”—though in those cases both parties are still in the wrong.

Let’s say Person A is smoking in a non-smoking area. Person B comes along and lights up. If Person A says “you can’t smoke here” and Person B says “Why not? You are.”

Person B is right to call out Person A’s hypocrisy, but really, neither should smoke in non-smoking areas.

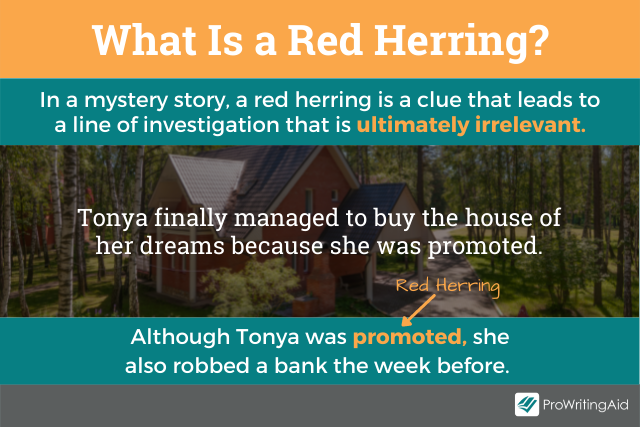

3. Red Herring

In a mystery story, a red herring is a clue that leads to a line of investigation that is ultimately irrelevant.

A red herring may look like a solid lead at first but ultimately proves to be a misdirection.

As a logical fallacy, a red herring is also a distraction; it’s a bit of “smoke and mirrors.”

For example:

- Families will have to pay more in community taxes under the new budget. But children are our future, aren’t they?

In this example, the implication is that increased taxes will help the children of the community, but will the tax money really go to fund children’s programs?

If, upon further budget inspection, the taxes go to anything other than children, then concern for the children represents a red herring.

Here’s another example:

Person 1: Why did you hide the truth from me? You know the truth is one of the most important aspects of a healthy relationship.

Person 2: But what is “truth” actually?

Nice try, right? The red herring is the detour into a philosophical discussion of truth rather than a discussion of why Person 2 was dishonest.

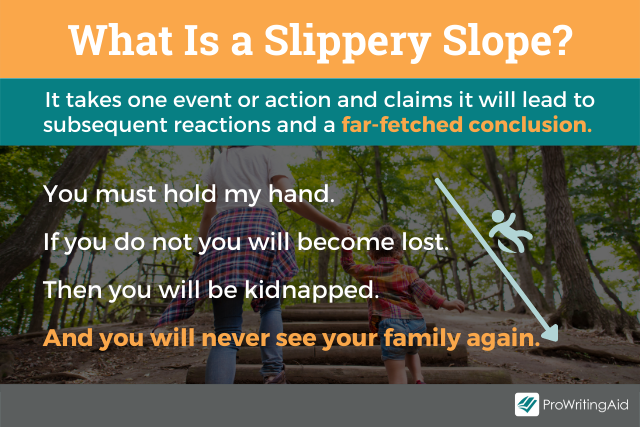

4. The Slippery Slope

The slippery slope fallacy takes one event or action and claims it will lead to subsequent reactions and a (usually) far-fetched conclusion.

Can you remember, perhaps, your parents using slippery slope arguments?

Kid: Can I stay out until midnight this weekend?

Parent: If you stay out after 10, you’ll end up hanging out on the street. If you’re on the street, you’ll hook up with some nasty characters. If you hook up with nasty characters, they’ll influence you to smoke pot. If you smoke weed, that will lead to harder drug use, and you’ll have to commit crimes to support your habit. Your life will be ruined.

Maybe you’ve read If You Give a Mouse a Cookie or other books from that series by Laura Numeroff.

They’re comedic, fun examples of the slippery slope, providing a demonstration of that not-necessarily logical chain reaction.

Interestingly, years-later discussions of the book show some folks argued the book had a political message—an argument that seems to have been a red herring.

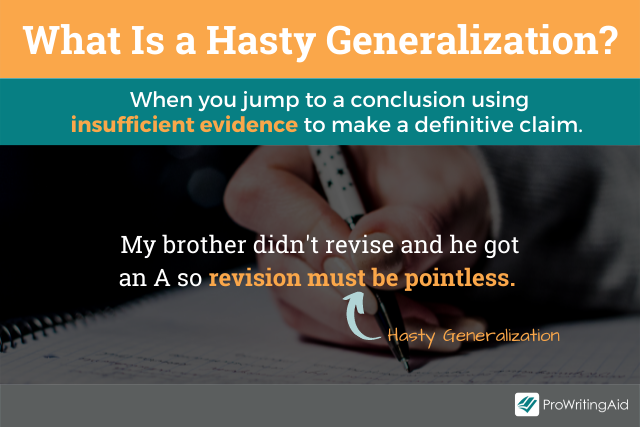

5. The Hasty Generalization

When you jump to a conclusion where there really isn’t one, you make a hasty generalization. You use insufficient evidence to make a definitive claim.

For example:

- My grandfather smoked unfiltered cigarettes and ate steak five nights a week; he lived to be 95. Cigarettes and steak cannot be that bad for you if he lived that long.

Good for grandpa! But to cite this one example as “proof” is irresponsible, especially considering other evidence that exists to show the dangers of smoking and of eating too much red meat.

- That news organization reported the president was in New Jersey when he was really in New York. See—the news really is all fake.

While it’s great that this person recognized an error, one error from one news organization is not enough to characterize all news as “fake.”

Stereotypes are examples of hasty generalizations.

If a person or small group from “that” race, ethnicity, religion, etc. committed a crime, then stereotypes conclude “everyone” from that group is a criminal.

Hasty generalizations often include absolutes: everyone, all, never, always. Be wary of arguments that use those terms.

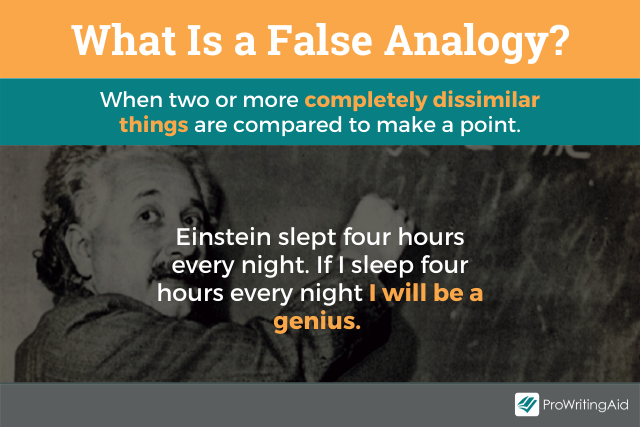

6. False Analogy or False Equivalence

When you compare two or more completely dissimilar things to make a point, you’re creating a false analogy or false equivalence.

For example:

- So we can put a man on the moon, but we can’t find a cure for the common cold?

Landing on the moon and finding a cure for the cold are both impressive acts. But that’s really the only way they’re the same.

- Running a school is the same as running a business.

Yes, schools and businesses both have budgets and they both have a chain of command, but their goals are different. A school seeks to educate; a business wants to make a profit.

The organic food ad example from the beginning of the post fits into this category as well.

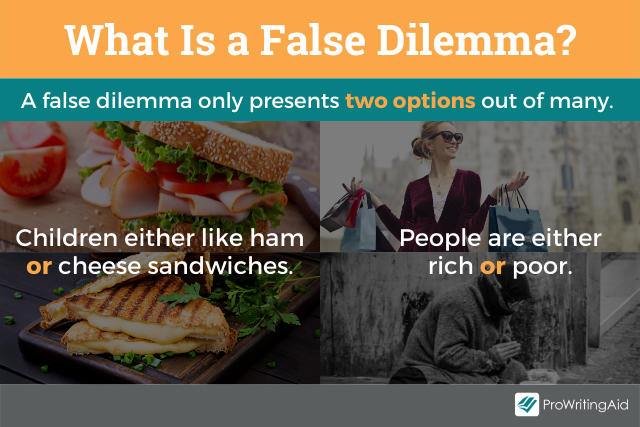

7. False Dilemma or False Dichotomy

In a false dilemma or false dichotomy, the argument is that you have two options—and that’s it.

For example, you might have heard the phrase “America: love it or leave it!” Are those really the only choices? Couldn’t we love certain things about the country but want to change others?

Other examples:

- You’re either for us or against us.

- If you don’t use our detergent, you’ll never have truly clean clothes.

- You either care about our financial future and vote for me, or you send our country into economic disaster.

If you’ve ever played the “Would You Rather” game, you’ve engaged with false dilemmas! As with If You Give a Mouse a Cookie, the game knowingly employs that fallacy for entertainment.

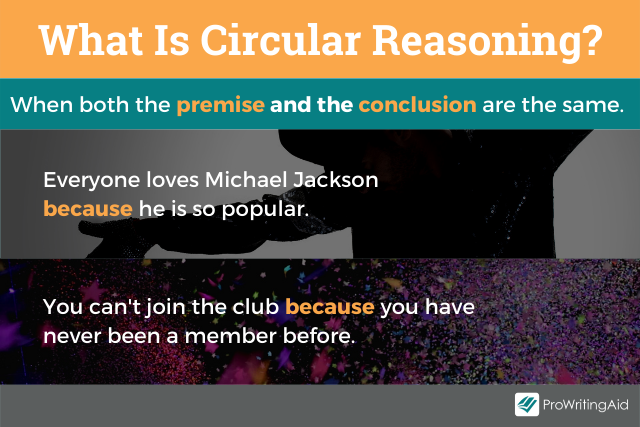

8. Circular Reasoning and Begging the Question

A circle goes round and round without really getting anywhere, and so does a circular argument. In a circular argument, both the premise and the conclusion are the same.

For example:

- Everyone loves pizza because it’s such a popular food.

- Drunk driving is against the law because it is illegal.

- We can’t hire you because you have no experience with our company.

While those examples are pretty clear, circular reasoning isn’t always so easy to detect. An often-used example of this is:

- I believe ghosts are real because I have seen a ghost.

In this example, there’s an assumption that what the person saw was actually a ghost. But maybe there was a trick of light; maybe a friend was pulling a prank; maybe the person had really been dreaming. Until the person can prove that what he or she saw was truly a ghost, the argument is based on circular reasoning.

The conclusion ghosts are real assumes the premise I have seen a ghost is true.

Begging the question is a type of circular reasoning, and often, the terms are used interchangeably. Frequently, people use the term “beg the question” when they actually mean “raise the question.”

For example, if someone says, Pat is smart, successful, and independent, which begs the question: why did she stay in such an unhealthy relationship?, this is really an example of raising the question.

When you beg the question, you assume the conclusion of your argument is true in the premise.

For example:

My chocolate chip cookies are the best because no one else can make chocolate chip cookies as good as mine.

- Premise: my chocolate chip cookies are the best

- Conclusion: no one can make chocolate chip cookies as good as mine.

9. The Bandwagon Fallacy

Have you ever used the “everyone’s doing it!” argument? This is the bandwagon fallacy. It presents the idea that because an activity, purchase, idea, etc. is popular, then it’s good.

For example:

- You have to let me go to the party! Everyone else’s parents have said yes!

- I don’t need to check with my doctor; everyone’s trying this weight-loss pill, and it’s working.

- Sixty-five percent of poll respondents support this policy, and you should too!

The bandwagon fallacy uses peer pressure to convince the audience of an argument’s legitimacy, but popular does not mean credible, and conforming is not necessarily “right.”

Even so, the bandwagon fallacy is powerful. Want evidence? Check out the Asch Conformity Experiments.

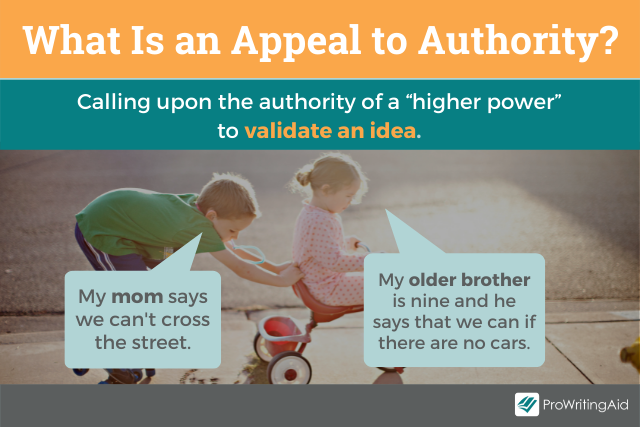

10. Appeals to (Apparent) Authority and Pity

Appeal to Authority

Calling upon the authority of a “higher power” generates this fallacy.

That higher power isn’t necessarily an authoritative source on the issue, or, if the authority is legitimate, other substantive evidence for the argument isn’t given.

When my daughter was in third grade, she and her friends were playing some kind of water-tag game at our community pool.

A disagreement erupted about a rule of the game, and one third grader said, “My friend Emily said the second line is base, and she’s in fourth grade!”

For the third graders, that settled it. The appeal to the authority of the wiser fourth grader was enough to convince them!

Advertisements often say “two out of three doctors agree that _ _ _ _ _ is the best medicine.” But we don’t hear why they came to that agreement or what “best” really means. And—which doctors?

Keep in mind that even if a legitimate, specific authority is named or is making an argument, you still need the opportunity to hear and examine the evidence supporting that argument.

Appeal to Pity

Emotions are powerful. Empathy is admirable and healthy, and is often the impetus for positive change. We should care about each other.

However, some arguments are built on manipulating emotions—laying on a guilt trip in order to convince someone to do something.

This type of emotional appeal can be exploitative and is not built on sound reasoning.

For example:

- Can you please increase my test grade? I studied so hard and tried my best, and will get into so much trouble if my grade is below 75 percent.

- If you don’t contribute money to our fund, these innocent animals will not have the food and shelter they need to survive. Do you want those lost lives on your conscience?

Final Tips to Help You Recognize Logical Fallacies

Whether you’re giving or receiving the argument, there are ways to protect yourself from logical fallacies.

Ask: What’s the conclusion of the argument? How could someone (or you) refute that conclusion?

Dissect the argument. List the evidence you offer (or that is offered) as support. How much evidence is there and how strong is it?

Be on the lookout for:

- Attacks on character

- Use of absolutes: all, none, always, never, etc.

- “Evidence” based on emotions

- “Shiny objects:” Fallacies are distracting and, like shiny objects, can take attention away from the issue at hand. If something sounds good but really isn’t relevant, don’t use it or follow it.