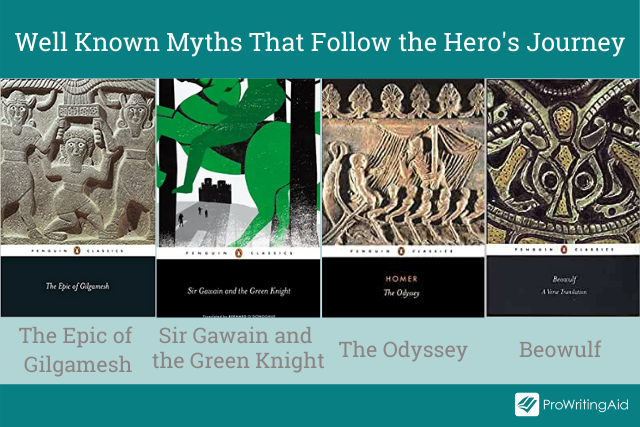

What do Star Wars, the legend of Prometheus, and the epic tale Beowulf have in common? They all follow the stages of Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey.

Whether you’re working on a novel or a short story, you can use the hero’s journey to plot and outline your work. If you’re new to the hero’s journey, start with our guide to using the hero’s journey as the backbone for your story.

The hero’s journey is so commonly used that it’s become an important narrative structure for any writer to understand. However, the idea that the hero’s journey is truly a "monomyth" is actually a myth of its own.

Understanding this narrative structure is important if you want to use it in your stories—but it’s also important if you want to subvert it and create something new.

Read on to see an analysis into how Joseph Campbell came up with the concept of the hero’s journey, as well as the common counterarguments to this well-known literary archetype.

- What Is Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey?

- How Did Joseph Campbell Develop the Concept of the Hero’s Journey?

- What Are the Three Stages of the Hero’s Journey?

- What Were the Original Seventeen Steps of the Hero’s Journey?

- What Are the Counterarguments to Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey?

- How Can You Use the Hero’s Journey in Your Writing Without Making Your Story Feel Formulaic?

What Is Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey?

The hero’s journey is an archetypal narrative structure found in stories from cultures all over the world. Because it’s such a universal narrative structure, the hero’s journey is also known as the "monomyth"—the single great story with many variations.

The term was coined by Joseph Campbell, an American writer and editor who was fascinated by myths from various cultures and literary traditions. He noticed that many heroic stories follow the same narrative stages, no matter which culture or time period they come from.

Since 1949, countless stories have used the hero’s journey archetype, from George Lucas’s Star Wars to Disney’s The Lion King.

How Did Joseph Campbell Develop the Concept of the Hero’s Journey?

Joseph Campbell was born in New York City in 1904. As a child, he took frequent trips to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West exhibition and to the American Museum of Natural History, where he became fascinated by the Native American exhibits.

He began noticing parallels between stories from the Christian Bible and stories from Native American religions, which made him wonder whether other mythologies might also share those commonalities.

As an adult, Campbell studied English literature at Columbia University. He read and analyzed classic religious and mythological texts, such as those of the Buddha, Moses, Mohammed, Jesus, and countless others. Over time, he became convinced that mythologies worldwide have many similarities, and that they shared a universal narrative backbone—a "monomyth."

Besides studying classic stories, Campbell also studied the work of early 20th-century analytical psychologists. In particular, he became fascinated with the work of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. This was crucial to the development of the hero’s journey, as the transformative aspect of the structure closely resembles Jung’s theory of death and rebirth.

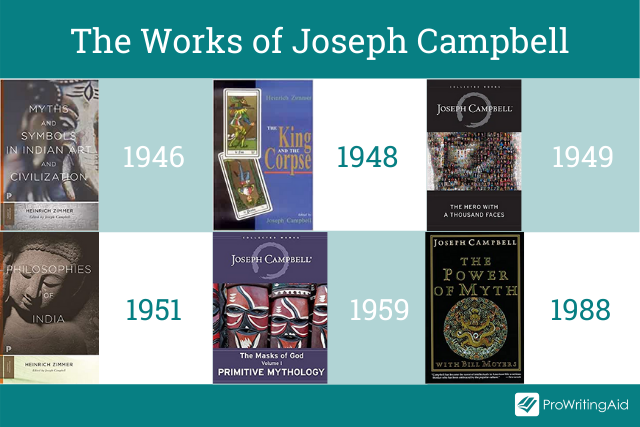

Campbell first coined the term "hero’s journey" in 1949, in his comparative mythology book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which was later adapted into the TV show The Power of Myth. In this book, Campbell outlined the hero’s journey in three basic stages and seventeen detailed steps.

He wrote and edited many other texts on comparative mythology and storytelling. Aside from The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), his other major works include Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization (1946), The King and the Corpse (1948), Philosophies of India (1951), The Masks of God (1959–68), and The Power of Myth (1988).

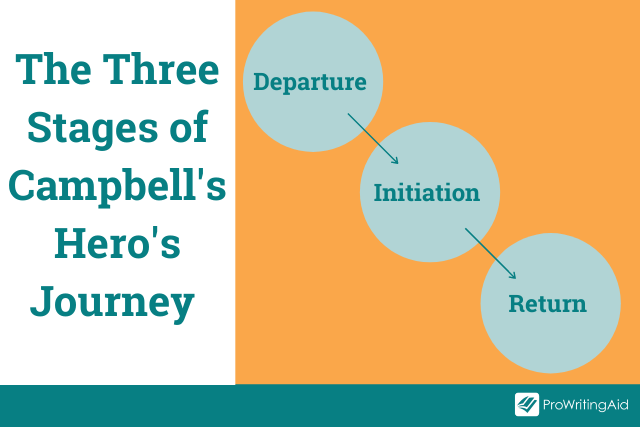

What Are the Three Stages of the Hero’s Journey?

In its simplest form, the hero’s journey can be described in three stages: departure, initiation, and return.

Departure: the hero leaves his home community to go on a quest.

Initiation: the hero faces trials and tribulations until he achieves victory on his quest.

Return: the hero goes home to his community with gifts and boons.

This is how Joseph Campbell summarized the hero’s journey in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949):

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Consider Star Wars, one of the most commonly cited examples of the hero’s journey.

In the departure stage, Luke Skywalker leaves his home planet of Tatooine with the goal of helping the rebellion defeat the Galactic Empire.

In the initiation stage, Luke undergoes various trials and tribulations on his heroic journey. He trains with Obi-Wan Kenobi to learn how to use the Force, rescues Princess Leia from the Death Star, and retrieves the Death Star plans and delivers them to the rebellion base. At last, he finally uses the Force to destroy the Death Star, fulfilling the purpose of his quest.

Finally, in the return stage, Luke returns to the rebellion base and wins a medal to commemorate his victory. He has helped his home world defeat the oppressive empire and gets to live as a hero.

What Were the Original Seventeen Steps of the Hero’s Journey?

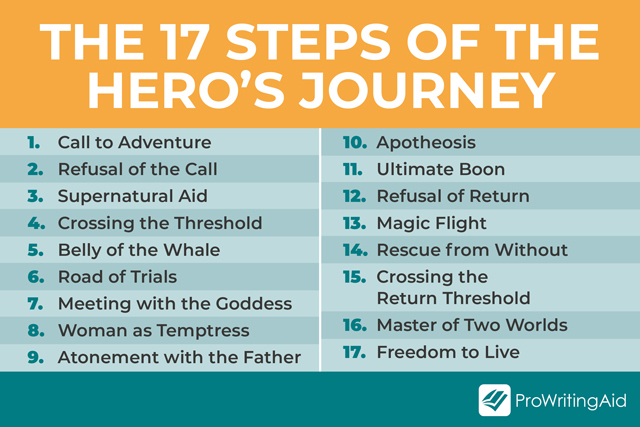

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell outlined seventeen detailed steps of the hero’s journey.

These seventeen steps were later simplified to twelve steps by Christopher Vogler, a successful Hollywood consultant, in his book The Writer’s Journey (1992). These twelve steps are more commonly studied by writers today, since they’re easier to learn and remember than Campbell’s seventeen steps.

Here is Campbell’s original hero’s journey structure:

Stage 1: Departure

Call to Adventure: The hero receives an invitation to go on a quest.

Refusal of the Call: At first, the hero hesitates to accept the invitation, either because the journey is too dangerous, or because they have other obligations at home.

Supernatural Aid: Someone the hero looks up to inspires them to accept the call to adventure, or gives them tools that will help them on their quest.

Crossing the Threshold: The hero begins their quest and leaves the ordinary world and their everyday life.

Belly of the Whale: The hero encounters the first real danger in their quest, and wonders whether or not to turn back—but ultimately pushes forward.

Stage 2: Initiation

Road of Trials: The hero undergoes several trials and learns from their mistakes.

Meeting With the Goddess: The hero meets a mentor figure or ally, who offers help or advice.

Woman as Temptress: The hero encounters temptations that threaten to steer them away from their heroic journey, which they must nobly avoid.

Atonement with the Father: The hero undergoes a personal metamorphosis by confronting an aspect of their own character that has been preventing them from achieving success, such as their own fear, greed, or self-doubt.

Apotheosis: The hero transforms into a better person, and goes forward with new insight and clarity on what they must do to win.

Ultimate Boon: The hero achieves victory in their quest.

Stage 3: Return

Refusal of Return: At first, the hero is reluctant to go back to the familiar world after their exciting journey and transformation.

Magic Flight: Even though the hero has achieved victory on their quest, they still face dangers as they try to return home.

Rescue from Without: An outside ally or mentor helps guide the hero safely home.

Crossing the Return Threshold: The hero returns to the familiar world, and tries to adjust to their old life.

Master of Two Worlds: The hero finds a balance between their home life and the person they become on their quest.

Freedom to Live: The hero gets used to their normal life and lives peacefully.

What Are the Counterarguments to Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey?

In the past seventy years, many writers and editors have criticized Joseph Campbell’s monomyth. After all, Campbell lived in a society that strongly valued heroic individualism, and his theories were a product of his time. Our society has evolved since 1949, but the hero’s journey archetype has failed to evolve with it.

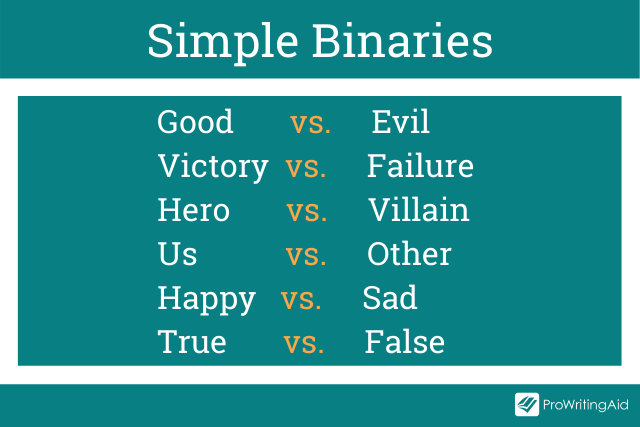

One of the most common criticisms of the hero’s journey is that it reduces the world to simple binaries: good and evil, victory and failure. If all stories followed the hero’s journey, writers wouldn’t be able to express a nuanced perspective of the world.

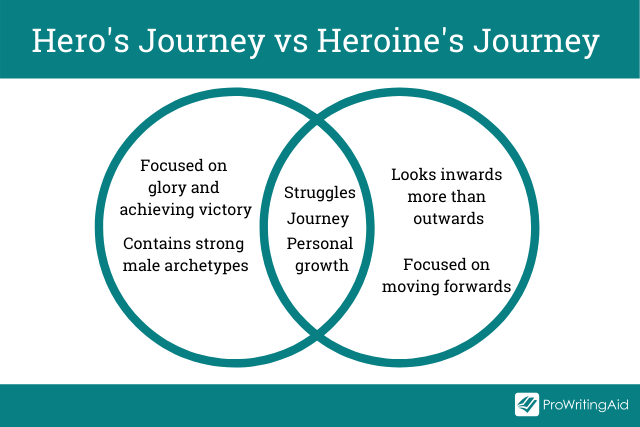

Another criticism is that the hero’s journey favors male protagonists, a tale about a hero leaving home to seek adventure in the outside world. In contrast, stories about women often involve looking inward, instead of looking outward, because of the domestic roles that women have traditionally been expected to fulfill.

The concept of the "heroine’s journey," also known as the female hero’s journey, was developed in 1990 by Maureen Murdock, a psychotherapist and a student of Joseph Campbell, in her book The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness.

Murdock wrote:

“The feminine journey is about going down deep into soul, healing and reclaiming, while the masculine journey is up and out, to spirit.”

Similarly, stories about people of color or marginalized groups within our society sometimes follow different story archetypes. Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey focuses on an individual hero, rather than a broader social context.

Stories about marginalized groups might center on communities reacting to oppression and navigating the rules set by the majority, instead of highlighting a single individual who proactively seeks adventure.

How Can You Use the Hero’s Journey in Your Writing Without Making Your Story Feel Formulaic?

There’s nothing wrong with using the hero’s journey in your own work. After all, it’s been spectacularly successful for thousands of years—there’s a timeless appeal to this story of adventure and spiritual transformation.

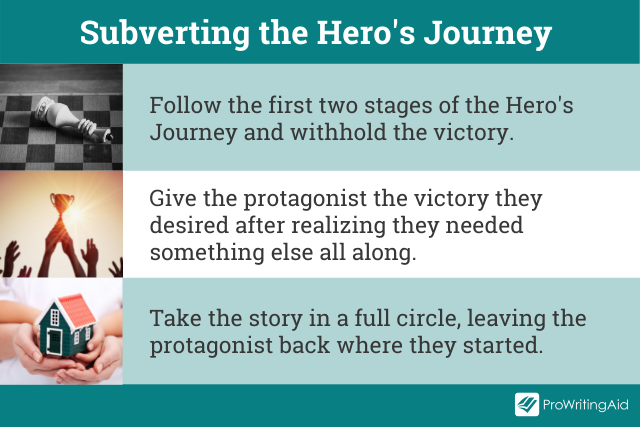

However, the hero’s journey can be a useful tool even if you don’t use it the way Joseph Campbell originally intended. Readers who recognize these classic tropes can appreciate an unexpected twist. Innovative literary fiction often plays with traditional narrative structures in new ways.

Many writers have subverted the hero’s journey archetype to better reflect the stories they want to tell. For example, you can follow the hero’s journey throughout the first two stages, then withhold the hero’s victory in the third stage.

Maybe the protagonist realizes they needed something else all along, rather than victory in their quest. Or maybe the story comes full circle and returns the protagonist back to where they started.

For more ideas, check out Steve Seager’s article on how to design a narrative more fitting to our contemporary context.

If it fits the needs of your story, consider changing up the hero’s journey in your own writing. You can build on Joseph Campbell’s time-honored literary tradition while also adding new twists of your own.