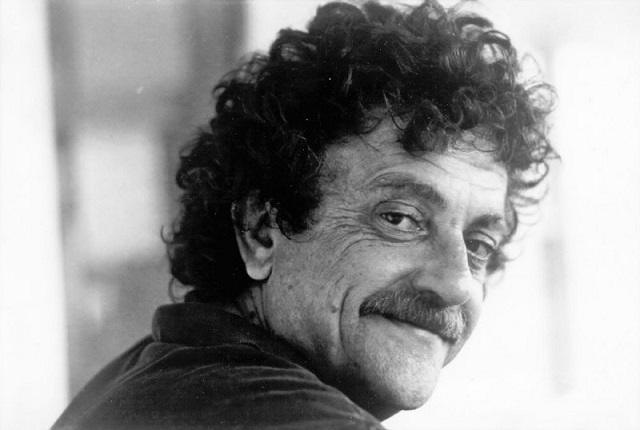

I can give you professional writing advice until the cows come home, but at the end of the day, I’m not a bestselling author or a member of America’s literary canon. You know who is? Kurt Vonnegut, that’s who.

Kurt Vonnegut, author of such classics as Slaughterhouse Five and Breakfast of Champions, stands today as one of the 20th century’s most important American writers. I can’t think of anyone better placed to give literary advice, and, thankfully, he agreed with me.

These eight tips were originally written by Vonnegut to apply exclusively to writers of short stories, but I reckon they’re just as useful for writers of longer fiction. Here they are:

The Tips

1. "Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted."

This one seems simple: your reader (a total stranger) must not feel like they’re wasting time wading through unnecessary details, events, or descriptions—they must feel constantly engaged. If you give them an excuse to get up and wander off, they’ll do it.

This tip is about keeping your story focused. Your plot must be structured in such a way that the central conflict is always in view (here’s more on how to structure your plot). Even tangential storylines need to be relevant.

2. "Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for."

This helps to keep readers engaged and on-side. Unsurprisingly, if everyone in your book is repellent, the reader will be repelled!

If a reader likes even one character in your story, they will feel invested in what happens to that character. This keeps them engaged and keeps them reading.

Who would have made it through all seven Harry Potter books if Harry, Ron, and Hermione were all insufferable brats?

3. "Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water."

This one is HUGE. Too often in short stories and novels, as well as on TV and in films, you see characters who arrive solely to fill some plot hole or who do nothing other than complement the protagonist.

For example, I was editing a fantasy novel recently where a new monster with some new adventurer-defeating ability would appear intermittently, only to be thwarted by some new arrival who would turn up unannounced, cast a magic spell to defeat the monster, and then disappear, never to be heard from again.

Why did he turn up? Who was he? What did he hope to gain by attacking this monster that wasn’t troubling him?

Your characters, even if they are monsters, should be believable as people—they should all have hopes, dreams, motives… even if that motive is, as Vonnegut says, a glass of water.

George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series is good for this. All of his characters have established motives that justify their horrible actions: Arya wants revenge on those who’ve wronged her family, Cersei wants to protect her children and exercise her power, and Hot Pie wants to make nice pastries.

4. "Every sentence must do one of two things: reveal character or advance the action."

This is particularly true for short stories but is also something to remember for novels. No line should be wasted—you have to be ruthless with your prose. Don’t be afraid to prune and hack whole sentences off. After all, if you don’t, your editor will!

For example, sometimes I’ll see descriptive paragraphs overloaded with flowery prose:

- Steven walked slowly and quietly into the kitchen. The units were glossy white and the worktop was a speckled grey. Behind the silver sink, seven small potted plants lined the window sill and brilliant sunshine weaved through the emerald green leaves, casting shadows on the patterned linoleum floor.

Now, as a descriptive paragraph this certainly conjures a vivid picture, but the writer should ask himself/herself what exactly such description is achieving. Is the kitchen a significant space in the plot? Do we really need to know about the units, the worktop, or the potted plants? Can we really justify two adverbs?

If the answer to these questions is no, the paragraph could be much improved:

- Steven crept into the kitchen.

In a short story, that’s probably enough.

5. "Start as close to the end as possible."

I was surprised by this one, but it makes sense. Short stories often fail through biting off more than they can chew. A good short story is intimate, limited in scope, and detailed in its characters, settings, and events.

Take John Cheever’s 'Reunion' as an example. It starts only a few hours from the end and focuses on only two characters in a few bars.

The story follows the narrator as he meets his estranged father for a drink, but the narrator’s father gets the pair kicked out of every bar they visit by being abusive to waiters. The story ends when they run out of time and don’t get to enjoy a drink together after all. The narrator goes to catch his train, leaves his father shouting at a newsagent, and is borne away. The story ends with the incredibly potent line: “and that was the last time I saw my father.”

6. "Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them in order that the reader may see what they are made of."

Every story needs an "all is lost" moment (or several!).TV audiences everywhere have learned the power of sadism through Game of Thrones, but this kind of cruelty isn’t exclusive to George R.R. Martin.

Terrible events make for good drama, and suffering serves to render characters vulnerable—and, as any good writer knows, it is only when a person is vulnerable that they can truly be known.

7. "Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia."

This tip is even more important today than it was in Vonnegut’s time. It’s about writing for yourself or for one person—never write for the sake of following a trend. As Strunk and White wrote in Elements of Style:

- Start sniffing at the air, or glancing at the trend machine, and you are as good as dead, although you may make a nice living.

Don’t be a sellout—write true, and write for yourself.

8. "Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages."

This is perhaps a surprising tip, and one that might not be suitable for writers of thrillers or horror fiction, but providing information aids in world-building, helps render events and characters believable, and, perhaps most importantly, will make any plot holes or instances of deus ex machina glaringly clear.

There are Exceptions!

Of course, some trailblazers can get away with ignoring all of these tips—Kurt had this to say of Flannery O’Connor:

- The greatest American short story writer of my generation was Flannery O’Connor. She broke practically every one of my rules but the first. Great writers tend to do that.

Well, back to the drawing board then.