In the world of novel writing, most authors are familiar with the terms “pantser” and “plotter.” These words are a generic label for your writing process. If you’re a plotter, or what some people call a planner, you spend a lot of time planning your novel before you ever sit down to write.

People who prefer to write by the seat of their pants are pantsers. Some writers prefer the term “discovery writer,” since you discover the story as you write.

Most people fall somewhere in the middle. But me? I am on the far end of the plotting spectrum. I have a multi-step planning process, and as a result, I spend less time on major developmental edits. I believe in the rule: the more time you spend plotting, the less time you spend editing, and vice versa.

My secret is the final stage of my plotting process: a scene chart.

The Case for a Scene Chart

When I first started writing, I ran into two common issues. The first problem I had came from my attempts to discovery-write. My stories were choppy and short. I’d hit 10,000 words or so and my story was done. But it wasn’t even a decent short story! My other issue was having too many ideas and no idea how they worked together.

Then I discovered Annie Neugebauer’s novel scenes chart. She has a lot of worksheets on her website, including various outline templates. But the scene chart changed my life. I’m not exaggerating! Without a scene chart, I doubt I would have ever finished my first book.

How can a scene chart help you plan your novel? Why not just use a regular outline? Here are a few advantages.

- Envision the story clearly before you write it

- Fix flow and pacing problems before the first draft

- Find plot holes before they develop

- Figure out where you need to add more detail

- Record notes about details and even dialogue you want to remember later

Neugebauer’s scene chart has space for point-of-view, setting, a scene summary, notes, and more. In the last several years, my own scene chart has evolved into something even more detailed. I note character motivations and which conflict the scene addresses.

A few years ago, J.K. Rowling’s plot spreadsheet went viral. She organized her plotting by month in the story and all the subplots. This method helped her keep track of all the various plotlines throughout the entire series.

I find that I get stuck far less often when I use a scene chart. I know where my story is going, but more importantly, I know how to get there.

I do offer this disclaimer, though. Much like the United States Constitution, your scene chart is a living document. As you write, things will change. A new scene idea will pop up that you didn’t have before. Your characters will stop cooperating. In my most recent first draft, a character was supposed to die, and she didn’t. The next scene was supposed to be her funeral. Oops!

Where Do I Start?

If I were to illustrate my plotting method, it would look like a funnel. To plot down to a micro level, you need to start with the big idea.

When I first start thinking about my stories, I usually imagine a specific scene or two. I jot those ideas down to add in my next steps.

Next, I start my timeline. I have written before about the advantages of using a timeline to plan or unstick your story. Without this step, I find creating a scene chart extremely difficult.

The Double Timeline

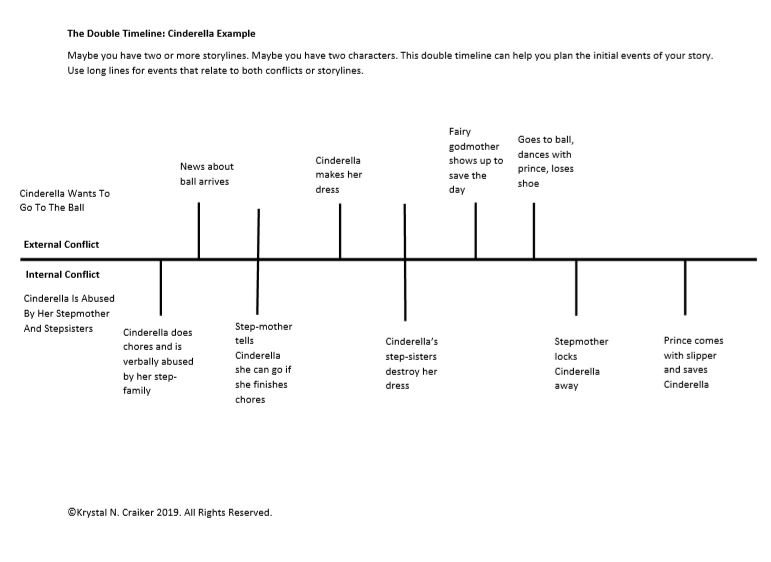

A regular timeline of events is a great place to start. But I have created a method called a double timeline. I actually learned this technique as a strategy for history classrooms, but I turned it into a plotting tool.

Most novels do not have one conflict. I start by identifying the major external and internal conflicts. There may be multiple aspects to each of these. In general, the external conflict is between my main characters and external forces. The internal conflict relates to the main characters’ personal growth.

For my first book, The Sage’s Consort, the mysterious attacks on the magical peoples in Elandria comprised most of my external conflict. The internal conflict was Quinn’s personal growth as a powerful Scholar. The romance was directly tied to Quinn’s development, so I included that in the internal conflict.

On top of my timeline, I plot the events that make up the external conflicts. On the bottom, I note the internal conflict events. At some point, I can see where these conflicts will merge and the storylines will tie together. Then I just pick a side to write the following events on. This usually occurs at or near the climax.

Try to start with the six to nine biggest events in your story. If I know my story’s beginning and resolution, I put those on the timeline first. Then put the climax down and fill in around those. If you’ve had any other scene ideas, try to figure out where those will fit.

Writing a Synopsis

I’ve recently added another step to my plotting process after I was asked to teach a workshop on novel synopses. I now do this step before my scene chart, so I’m including it here.

A synopsis is a roughly two-page summary of your entire story. If you’re pitching your book to agents, many require a synopsis. As an indie author, I didn’t need this step, but I found it a helpful planning tool. In a funny twist, as I was creating the slideshow for this workshop, Annie Neugebauer advertised an online course with a similar premise: write the pitch first!

I take those big events from my timeline and write a couple of pages summarizing my whole story. If that seems like a lot, try writing a rough draft of a book blurb that could go on your back cover. If this isn’t your cup of tea, you can try an outline format, as well.

The Scene Chart

If you search Google for “novel scene chart,” you’ll find a lot of different templates. Some are very basic. Others are color-coded and detailed. I make my own in Google Sheets. But overall, a scene chart will be a table or graph that you can easily look at and see what’s happening next. I’ve seen charts that stay in a timeline format with more detail. I’ve even seen circles and mind maps, but I’m far too linear of a thinker for that.

A scene chart needs a few basic components, then you can add anything else you think would help.

- Setting

- Characters present

- Summary

- Notes

- Point-of-view, in a multiple POV story

I also note my expected word count, character goals, timing, and which conflict and themes are being addressed.

Now, you’ll want to revisit your timeline. You will have a handful of events that need to occur. Now you have to connect the dots. How do you logically get from one event to the next?

The advantage of using a table in a document or spreadsheet is that you can add rows between events. But you can also handwrite your table just like J.K. Rowling. You can even use notecards on a whiteboard or corkboard and manually rearrange your scenes.

Start with your opening scene and imagine your story playing out in your mind. What do your characters do next? What breadcrumbs do you need to drop early on for later points in the story?

I start by only writing a few word summary of the scene and any notes. Don’t feel obligated to fill in every column right away.

I spend several weeks finalizing my scene chart. Once you fill in what you think will be nearly every scene, take a look at it and ask yourself a few questions.

- Do I see any major plot holes?

- Does the order make sense?

- Where can I add or take away scenes?

- Have I built up every conflict?

- How do my characters grow throughout this story?

Make changes as you see fit. Now you’re ready to write!

Final Thoughts

When I bring my early drafts to my critique group, I get compliments on my pacing and have very little developmental changes necessary. I consider my scene chart my “bad first draft.” This frees up my editing time for my other weaknesses, like imagery and description, passive voice, and the dreaded accidental point-of-view shifts.

Your scene chart is your guidebook, not your navigation system. You can make detours and changes, and you will! If a major shift occurs early on, I usually edit my scene chart to reflect this. If it’s toward the end, I just keep writing and make my changes mentally.

If you’re struggling with finding a plotting method that works for you, I encourage you to try a scene chart. Do you only want to plan chapter-by-chapter? That’s fine. This method works for that, as well!

A scene chart fits in nicely as an added step to whatever your current plotting method is. There’s no right way to write, but a scene chart can improve your process and make writing your novel flow even better.