The term “cinematic writing” is a popular one these days, often trumpeted in starred reviews of bestselling novels. Who among us wouldn’t want their writing described as “cinematic” given we live in an era of moving images in which novels compete for attention with movies and video games?

But many of us in the early stages of our careers conflate cinematic writing with long, drawn-out descriptive passages of sunsets and landscapes that risk leaving our writing feeling flat and lifeless. This gets even worse if the scene in question has action in it.

That’s why, when I’m writing a scene that’s desperate for a sense of dynamism, I turn to my writer’s camera.

The Wide Shot

Dale punched Frank in the jaw.

What’s wrong with that sentence? Is it too simplistic? Too cliché? Have we committed the heresy of “telling not showing”? Nope. Let’s look at it again:

Dale punched Frank in the jaw.

Simple sentences are fine. They’re clear, readable, and don’t impede the reader’s experience of the story. There’s nothing overtly clichéd about a good old punch-to-the-jaw moment, either. Oh, and this line is, in fact, showing rather than telling (though that distinction often falls apart in practice—which might be why, as Lee Child sometimes says, we’re called storytellers not storyshowers).

So the simple fact is that there’s nothing inherently wrong with this line. If it works for you as a writer, go ahead. The problem comes in when we string too many of these together:

Dale walked into the room. He punched Frank in the jaw. Frank fell to the ground, shook himself off, and got up again.

Notice how, even though people are doing things, getting punched and whatnot, the scene feels static and distant. You might try to cure this with changing the POV, but it doesn’t really get any better by putting it in the first person:

Dale walked into the room. He punched me in the face. I fell to the ground, shook myself off, and got up again.

See? Still not particularly exciting. We’re still essentially in what a filmmaker would call a wide shot. We can see everything that’s happening, but we’re not really focused on anything in particular. The line is fine if you’re aiming for a dispassionate, almost reportage style of writing. But if you want to to put the reader in the action, you’ve got to move the camera.

The Closeup

What if we put our writer’s camera just over Frank’s shoulder? This will do two things: first, it puts us in Frank’s point of view (regardless of whether we’re writing in first person or third), putting us in his shoes as someone about to be punched. Second, by limiting what we’re about to see we also keep it from being so generalized that the action loses any meaning.

Let’s try a simple version:

Frank barely had enough time to see Dale’s fist coming before it caught him square in the jaw.

Not bad. This line definitely puts us closer into the action. By the way, the effect isn’t the result of more words being used to describe the punch—we’ve just focused our attention on Jim’s fist rather than on the entire character.

From here we can decide whether our next line is another closeup:

Frank lost his balance and watched helplessly as the cold linoleum floor rose up to meet his face.

But maybe that feels too contrived for your taste and makes too much of the image of the floor. If you prefer, switch back to a simple wide shot:

Frank lost his balance and fell to the cold linoleum floor.

This is the first principle to remember: there isn’t one right way to write each piece of action. The idea here is to build up a toolkit from which you can choose different ways of describing each moment and put them together in a sequence that feels emotionally powerful to you.

Now, let’s go back and explore some other ways of writing that punch, because the great thing about the writer’s camera is that it’s capable of a multitude of shots.

The Extreme Closeup

Extreme closeups focus our awareness on individual elements to make them suddenly much more significant. In doing this, we can make interesting and unusual choices as writers. For example, instead of just focusing on Dale’s fist, what if we go in even closer?

Frank could’ve counted the short, curly blond hairs on Dale knuckles as that big, meaty fist came straight for his jaw.

Starting to feel a little film noir, perhaps? That’s not by accident: noir stylists like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler were masters at putting the reader in the thick of the action. This also helps distinguish Dale from all the other characters in your book. Whatever comes next, the reader will always remember those curly blond hairs on his knuckles.

Our writer’s camera can focus in as close or far as we want to when writing each moment of a scene, but that’s not all it can do, because while filmmakers are limited to the senses of sight and sound, we fiction writers have access to all five.

Putting on the Sensory Lens

There’s nothing new about the idea that writers should make use of all five senses, but too often we apply it to static, establishing descriptions as we enter a setting:

The narrow cavern walls were slick with damp moss that felt like wet, sagging flesh to the touch. The air stank of sulphur and gasoline, and Eliza had to keep her mouth clamped shut to avoid the taste of it on her tongue.

Depending on your personal style, those lines might be fine, but only thinking of the senses of touch, taste, and smell when describing a setting wastes a remarkably versatile tool. So let’s put the sensory lens on our camera and shoot that punch again:

The smell of a lifetime's worth of greasy cheeseburgers wafted from Dale’s knuckles, and as they collided with Frank’s face, callouses that had worn down dozens of gym bags scraped the skin off his jaw. A copper taste filled his mouth where his teeth had bitten down onto his tongue.

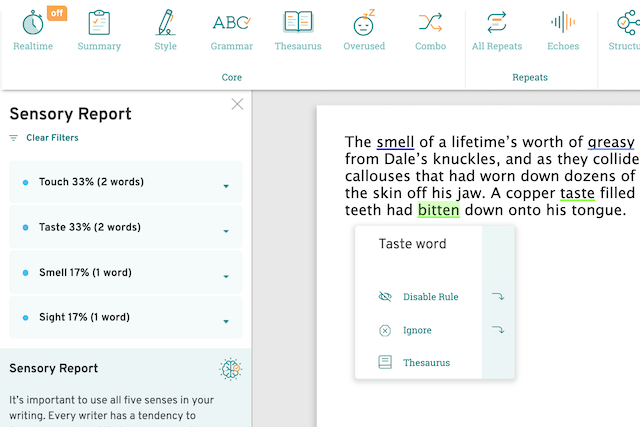

Notice how the closer we move our camera in, from the wide shot to the closeup to the extreme closeup to snapping on our unique writer’s sensory lens, we put the reader closer into the experience of the action. If you want to see how you’re using the five senses at a glance, try ProWritingAid’s Sensory Report.

You’ll see how many of each type of sense word you have used and how they are distributed through your document. If your writing feels slow or stale, try switching to a different sense to bring a new perspective.

How close you want to get is up to you as a writer and how important you want to make this particular punch to your story. Maybe you want something less visceral—something that almost makes the punch itself irrelevant. What if we want to pull our camera so far back we’re not even seeing the punch at all but the idea of the punch? Well, we can do that, too, because as writers we have options far beyond those available to filmmakers.

The Conceptual Lens

Writers aren’t limited by the five senses the way most other artists are. We can go beyond describing a simple action to exploring questions about what those actions mean. We can even pull those moments out of time and space entirely:

How many people out of the seven billion currently infecting the earth with their petty rivalries, jealousies, and just plain meanness were punching somebody at that exact moment? Frank couldn’t guess, but it had to be more than just a few, which made Dale’s fist colliding with his jaw feel strangely banal.

Notice how we’ve pulled so far back from the punch itself that we’re not looking at Frank or Dale or anyone in the scene at all. We’re describing this piece of action in thematic terms so the punch has become a symbol of the trite nature of humanity’s propensity for violence.

Making Choices

I’ll leave you with two simple exercises that need not take up more than a couple of minutes each but which might add to your choices the next time you’re faced with a passage that just doesn’t feel alive to you.

Let’s start with a very quick one. Look at the four lines below and rewrite them in your head using whichever shots we’ve described above (wide, closeup, extreme closeup, sensory lens, and conceptual lens) that you want.

- Dale walked into the room.

- Dale punched Frank in the jaw.

- Frank fell to the floor.

- Frank pushed himself back up to his feet.

Dull as doornails, right? But now play with the camera in your mind a little, trying different shots for each line and see if there’s a sequence of shots that makes those four drab lines come alive into something emotionally resonant and meaningful to you.

The second exercise is to take a passage from your own work—something that you skim over when re-reading the scene. That’s often a cue that something’s not working. Take a paragraph or two and ask yourself which shots you used. Were they all wide shots that just described the action? Did you try to mask an otherwise dull sequence with clever turns of phrase or unnecessary verbiage? Maybe there’s an opportunity here to do something a little different that reignites the scene for you as the writer.

Playing with the Camera

Let me leave you with three final thoughts.

First, while we’ve applied these techniques to what looks like the start of a fight scene, never forget that they can work just as well with two people about to kiss, or sitting on a train, or casting a magic spell.

Second, while I’ve outlined a few techniques here, this is by no means an exhaustive list. There are plenty of other shots and other lenses to bring into your writing and discovering them for yourself is part of the fun. So take a minute and try to come up with your own special shot. Even a casual search on the Internet for “camera shots” will turn up loads of options just waiting for you to interpret your own way.

Just as an example, think of the fisheye lens, which distorts shapes and sizes of what it sees. Feels a bit dreamy, doesn’t it? What if that punch we’ve been describing is distorted to Frank’s eyes, as if Dale’s fist were gigantic compared to his body? Again, the same piece of action produces a markedly different experience for the reader.

Finally, remember that just as you can over-write your scenes with convoluted jumbles of adjectives and adverbs, you can just as easily over-direct your scenes. Part of the skill of using the writer’s camera is learning when to let those good old wide shots do the job they were meant to do. Many dialogue scenes, for example, work best when you just let the words spoken by your characters carry us along.

The key, as always, is to let these techniques be tools in your belt to be used when your own intuitive sense of style calls for them.

Start editing like a pro with your free ProWritingAid account

When a reader sees a grammar error, they start to lose faith in the writer who made it.

ProWritingAid is one of the best grammar checkers out there—but it's far more than that! Our editing tool also looks at elements of structure and style that have an impact on how strong and readable your writing is.

More, it helps you learn as you edit, making you a better writer every time you use the program.

The best way to find out how much ProWritingAid can do is to try it yourself!