More authors than ever are self-publishing. This requires them to learn new skills or to hire professionals to perform services that conventional publishers typically would do (or used to do) for authors, including some aspects of editing.

Many writers still mistakenly believe that editing equals proofreading. That’s a dangerous misconception in the competitive marketplace where putting your best work forward is mandatory, whether that’s directly to the reader or to an agent or publisher.

While authors who’ve worked with a publisher likely understand that good editing isn’t just one pass through the manuscript, many writers don’t know that there are different stages or phases of editing. Nor do they realize that independent editors specialize (or should) in one or more of those stages.

So let’s unpack the editing toolbox to understand what’s there, and then we’ll take an especially close look at line editing, the one type of editing you do not want to omit from your writing and publishing process.

A Primer on Editing Stages

First, please understand that industry professionals, including editors, use various names or labels for the different types of editing. That certainly doesn’t help writers. It’s confusing, even to editors. So let’s establish some definitions for the purpose of our discussion here.

Even my definitions aren’t comprehensive nor distinctly delineated—and can’t be, really. The boundaries between the stages are not firm. The art and craft of writing and revision are fluid and subjective. Undoubtedly, someone will disagree with parts of these definitions, but let’s work with them for now, so we have a common base of understanding.

Developmental editing is typically begun in the early stages of a manuscript while it’s still being created. A developmental edit focuses on issues related to story, organization, clarity, and overall structure, as well as authorial voice and style. As the writing progresses, the developmental editor will assure the author’s original intent and vision for the manuscript is maintained.

In my experience, developmental editors tend to be hired more often by non-fiction authors than fiction authors. Sometimes the developmental editor will act as a project manager, seeing the non-fiction project through every step from conception through publication.

Content editing is similar to developmental editing in that it focuses on overarching or “big-picture” issues in the manuscript. The main difference is that the content editor doesn’t begin working with the author until the manuscript is complete.

In addition to clarity, organization, voice, and style, the content editor who works on fiction also will consider character and plot development and their arcs, point of view, tone, theme, conflict and tension, among other storytelling elements. Content editing is sometimes called structural or substantive editing.

Line editing, more than any other phase of editing, is about the writing. It is a scene-, paragraph-, and line-level assessment of the manuscript to improve the writing style and assure flow and readability. Elements such as transitions between chapters and scenes, tonal and point-of-view shifts, repetition, redundancies and digressions, ambiguities, and pacing should be noted and resolved during a line edit.

Particular attention is paid to the artistic aspects of writing, such as theme, noting when it might need elaboration or further explanation. Though checks for sentence fragments, unnatural dialogue, and clichés are usually done in this phase, the line edit is not a grammar check; that’s the function of copy-editing.

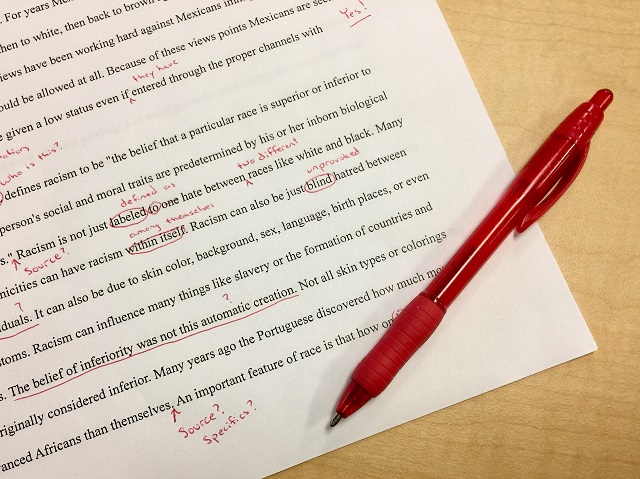

Copy-editing and line editing are often used interchangeably, but they differ in that line editing is more subjective while copy-editing is a rules-based approach to making word-by-word corrections in the manuscript. A copy-edit focuses on spelling, grammar, and punctuation checks, and also involves appropriate word choice, word repetition, as well as continuity and consistency of items such as any unique character or places names, capitalization, and hyphenation. A copy editor should have a solid understanding of the technical aspects of writing.

Proofreading, though often called editing, isn’t editing at all. It’s done at the last stage before publication and is a final pre-press check to make the manuscript as error-free as possible. Spelling, punctuation, and typos are the focus. If the proofreader is given an ARC (Advanced Reader’s Copy) to work from, they also will check elements of the layout and formatting, such as proper page numbering and appropriate page headings.

With those definitions, we now have some context for talking about line editing, how it relates to the other phases of editing, and why it’s important.

Why You Shouldn’t Skip Line Editing

Some smaller publishing houses provide developmental editing, followed by copy-editing, leaving out the line editing stage altogether. Even academic writing programs tend to offer courses on developmental editing and/or copy-editing, but not line editing. If there’s so much inattention to line editing, why bother with this phase at all?

Line editing focuses on the prose—assuring creative and concise language—and effective execution of the story, both of which are vital for holding your readers.

Additionally, while those publishers noted above who skip line editing might double down on content or copy-editing to make up for their lack of attention to this phase, they’re probably inclined to accept manuscripts from strong writers who’ve done the work of self-editing before coming to them. It goes without saying that the same is true for agents too.

While it takes time to learn how to line edit effectively, it’s one of the most valuable skills for a writer to have. This step in the editing process has the greatest potential to foster an author’s writing skills and bring out their unique voice.

Do It Yourself

Some important aspects of line editing for an author to learn include:

- scene structure

- maintaining your chosen point-of-view

- the difference between the author’s voice and the character’s voice and when to use them

- understanding tension, conflict, and pacing, and how they relate to and play off one another

- creating plausible characters with goals, motivations, and stakes

Other things to look for during line edits are overused words and excessive use of adverbs. When making revisions at this stage, be sure to get rid of purple prose, resolve sentence fragments, and untangle confusing sentences. Identify and resolve places where you’ve over- or under-described, invoked clichés, or used awkward or unnatural dialogue. Here’s a great checklist of line editing skills to learn.

This is a lot, I know. And becoming proficient at identifying these things in your own writing doesn’t come easy, even for the most studious and fastidious writers. Line-editing skills come with study of the craft through workshops and other learning opportunities, reading well-written books, and practice, practice, practice (i.e. words on the page, plus revision, revision, revision).

Lisa Lepki’s article “How to Edit Your Manuscript” offers a few more line-editing tips you can implement yourself. But if all this seems too overwhelming to tackle on your own, consider working with an editor.

Seeking Professional Help

Hiring a line editor is a good option if you feel confident about your story but have struggled with the prose—the artistry of the words. Working with a line editor can help make your writing more concise and streamlined. A good line editor can identify places where your style deviates. Perhaps most importantly, she can help you develop a strong and consistent voice.

Though some line editors might point out blatant plot holes, it is not the line editor’s responsibility to correct or identify issues with the plot or characterization. So resolve story issues in your manuscript either on your own or with a developmental or content editor before beginning line edits.

Some editors have a wide range of skills, but more than one type of editing cannot be performed effectively in a single pass through a manuscript. So before hiring a line editor, be clear about their expertise and focus. And ask how many passes they would make through your manuscript.

Look for a line editor with a teaching heart, one who doesn’t just make changes without explanation, but who provides suggestions and offers alternatives and examples so you can learn and carry forward your new line-editing knowledge into your next manuscript.

Get Your Story Read

Despite some common misunderstandings and confusion about what line editing is, it is the editing phase where the author has the greatest opportunity to make their writing stand out and shine above the rest. Giving due attention to the line editing phase—either on your own or in partnership with an editor—can make your storytelling flow and provide the greatest chance to grab and hold the attention of agents, publishers, and readers.