Since the invention of celluloid, Hollywood has adapted popular books and memoirs into hit movies.

From murder-mysteries like Delia Owen’s Where the Crawdads Sing, to Stephen King’s horror stories like Firestarter (adapted twice!), to Cheryl Strayed’s memoir Wild, movie studios rely on finding great books they know will translate into great films—and a big box office.

Books may be the best source material for movies and TV shows, not only because they have a built-in fan base, but also because they have all of their characters and storylines fully developed.

Some novels, particularly mysteries, are easily told in a two-hour movie format, but others with multiple storylines and characters, like Game of Thrones, translate easier into an episodic TV format.

Now, you can definitely get your book some Hollywood attention by entering screenwriting competitions like the ScreenCraft Cinematic Book Writing Competition, which puts your work in front of Hollywood judges who will adapt your work for you.

Or—you can adapt it yourself.

If you have written novels or a memoir and are interested in crossing over into film or TV, there’s nothing stopping you from digging into your page-turning book and transforming it into an edge-of-your-seat screenplay.

If you are a visual writer, if you create fascinating worlds, and if your characters leap off the page, these are great reasons to try your hand at switching mediums and turning your literary story into a cinematic one. As writers, it’s always fun to push the boundaries and try something new.

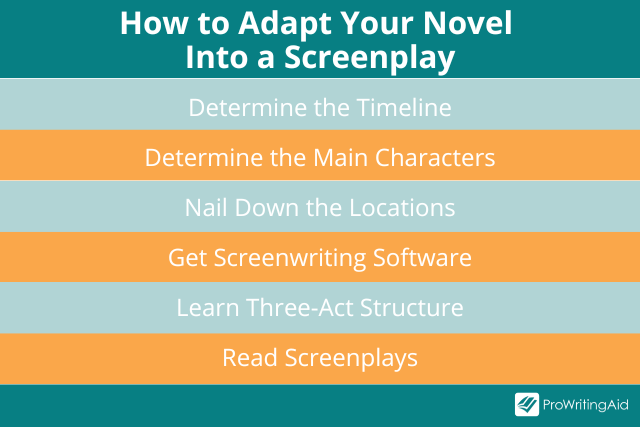

Here are six steps for turning your book into a screenplay.

Determine the Timeline

Some books tell stories that span over years or even generations. There are plenty of movies that do this successfully (2001: A Space Odyssey takes place over a couple million years). But keep in mind that in a film, you only have about two hours to tell your story.

Decide on the timeline for your story: does it take place over a few days, a few weeks, a few months? The more condensed your timeline is, the better. Your job is to pack as much conflict into those two hours of screen time as possible.

If your story jumps around in time, that’s fine—many movies use flashbacks and flash-forwards—but for now, map out your story in a linear timeline so you can be clear about the chain of events in the story.

From there, you can determine when and why you might want to move an event around in time. If you put each major event onto an index card, you can lay them out in a horizontal line and then decide which events you want to flash back or forward to and move them around.

Determine the Main Characters

You have a protagonist and an antagonist. But you need to determine the other main players. Ask yourself, “Which characters are absolutely crucial to telling this story?”

If you have a lot of characters, you may need to condense two or three characters into one. The fewer the characters, the easier it will be to tell your story in screenplay format.

Nail Down the Locations

Where exactly does your story take place? Is it an action thriller that spans the Communist Bloc of Eastern Europe in the 1980s? Or does it take place at a cabin in the woods?

You don’t have to worry about limiting the locations, but it is important to only include locations where the main plot is happening. Let these locations anchor your characters to your story.

Get Screenwriting Software

Using professional screenwriting software is a must. The good news is that you don’t need to use a pricey one like Final Draft, there are many good options and some are even free.

Do some research and enjoy the benefits of the software that will help you the most. Trelby, Highland, Movie Magic Screenwriter, Writer Duet, etc. are all good options and only take a few minutes to learn how to use.

The software is important because the format is designed to have each page equal one minute of screen time. If the format is off, an experienced producer can tell just by looking at the page.

Learn Three-Act Structure

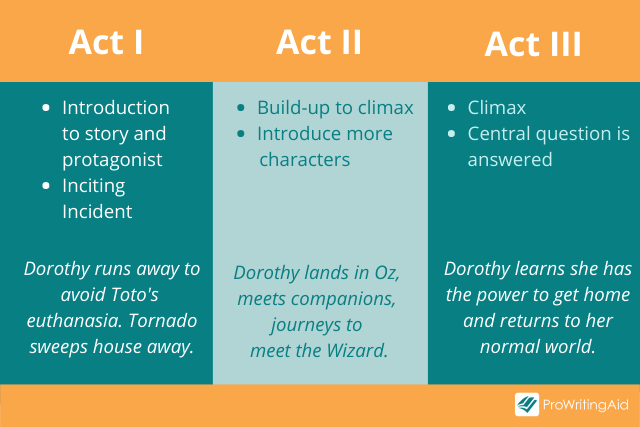

For a story to feel like a movie, it needs to be in a three-act structure.

Most likely, your book is already in this structure, whether or not you know it. But not all great novels follow this structure. In Hollywood, studios and producers rely on this three-act structure for efficient and satisfying storytelling.

There are numerous books that can help you with structure—one very accessible book is Save the Cat by Blake Snyder. While it may not be the most nuanced or in-depth book about screenwriting, it is an easy read and will get you started.

In the meantime, here’s what you need to know. I like to use the film The Wizard of Oz to illustrate the three-act structure because it clearly delineates the acts using color: Act I is in black and white, Act II is in color and Act III is again in black and white. It couldn’t be clearer!

Act I

This is the introduction to your story and your protagonist. It is the “set-up” for the rest of the story.

Everything your audience needs to know about your protagonist is laid out in the first act, or the first 25–30 pages of your screenplay. Keep in mind that a screenplay should be about 105–120 pages total.

One important element of Act I is the “inciting incident.” It is the event that sends your protagonist on a journey. Usually, your protagonist is reluctant to go on this journey but finds no way around it.

In The Wizard of Oz, it’s when Miss Gulch gets permission to euthanize Toto and the protagonist (Dorothy) runs away with Toto to protect her beloved dog. The inciting incident should take place around page 10 and no later than page 17. This event sets the entire story in motion.

Act II

As mentioned earlier, in The Wizard of Oz, the whole second act is in color. Dorothy is introduced to Oz, given the ruby slippers, and given the task of getting the Wicked Witch of West’s broom.

The second act is her journey down the yellow brick where she collects companions (Tin Man, Cowardly Lion, Scarecrow) who help her on her inner journey of self-discovery that will facilitate her coming-of-age.

Act III

The third act of a screenplay is most notable for having the climax of the story. Here, the central question of the story is answered, and the protagonist has most likely experienced emotional growth and changed for the better.

In The Wizard of Oz, act three technically starts while Dorothy is still in Oz, where she’s still in Technicolor. It’s when the Wizard gets in his hot air balloon and takes off to America without Dorothy.

She thinks all is lost and that she’ll never get home until Glinda the Good Witch tells Dorothy she’s had the power to return home this entire time—she just had to learn to believe in herself.

After all her trials and tribulations, Dorothy now clicks her ruby slippers and returns home a young woman with a newfound confidence. The black and white scenes at the end of the film show Dorothy as her new self in her old world, where harmony is now restored.

The best thing to do to learn film structure is to watch films in the same genre in which you’re writing. Take notes and watch the clock—in a two-hour film, Act II will begin around 25–30 minutes in and Act III will begin around 85–90 minutes in. The more you study these movies, the clearer the three-act structure will become.

Read Screenplays

The absolute best way to learn how to write screenplays based on a novel is to read screenplays that have been adapted from novels. After reading just a few, you’ll be surprised how familiar (and predictable) the structure becomes. The more you read, the more you’ll see how screenwriters altered, shifted, or edited a novel to fit into the three-act structure.

We can’t say that adapting your book to a screenplay will be easy, but it can be a highly rewarding challenge if you commit to the process. At the very least, it will help you grow as a writer and understand your story in a new light.