Table of Contents

If there’s one thing most writers have in common, it’s that we’re forever wondering how we can do better next time.

Whether you have a draft you want to improve or you’re looking for advice to help you with your next idea, here are some of our top suggestions for how to write a better story.

Focus on Your Characters

Here are some steps to take to make your characters even more compelling.

Get Clear on Arcs

A character’s arc is how they change throughout the story. They might overcome a flaw, grow emotionally, or discover they need something quite different from what they thought they wanted at the start (often all the above).

To make the arc satisfying, let the reader see the change in action. How can you show those shifts through the decisions the character makes, how they act, and what they say?

Arcs aren’t just for protagonists, though those are likely to be the most well-developed. Where you can, giving side characters and even antagonists space to grow and change can add emotional depth to the story and open up interesting possibilities for the plot.

Not every character needs an arc, though. So-called static characters (who stay mostly the same) can provide stability. It’s also sometimes more realistic for someone to stay the same. They can also enable you to focus more on the plot, as with detectives in “whodunits.”

In short stories, arcs are still important. However, because you have less room for development, you potentially have to take even more care to make them feel natural and earned.

You might pick one specific change or realization to focus on. Alternatively, you might show a small segment of a broader arc and hint at the possibility of change, leaving the reader to imagine what that might look like and what the implications might be.

Understand Their Motivations

Make sure your characters never do something just because the plot needs them to. They need to have a reason for every decision they make, and a reader has to understand what that reason is.

Think about every scene in terms of what your character is trying to achieve. Their actions and reactions need to be consistent with who they are, what they want, and what they know at this precise point in the story. Otherwise, it won’t feel consistent.

Give Them Agency

Understanding what motivates a character is key to giving them agency in the plot: the sense that they are influencing what happens to them through their choices and not just being swept along from A to B.

As a general rule, a character with agency and motivations that a reader can understand is far more engaging than one who just acts like a passenger in their own story.

Think about your plot and how your characters’ motivations and actions tie into it. If they have no influence over what happens whatsoever, you probably need to make some adjustments.

Ask yourself how you could show your character trying to influence things to achieve what they want at that point in the story. Remember, they don’t always need to be successful—their choices could even make things worse.

They also don’t need to start out by taking charge. They might make a shift from being reactive to proactive throughout the story—that could form part of their arc. There could be a moment or series of moments that convince them to change things for themselves.

Of course, in some stories, a character’s powerlessness is an important aspect of the plot. You want this to be an intentional feature, not an unintentional bug, though.

Deepen Characters With Relationships

Make sure your character relationships are working hard.

You can use them to deepen a reader’s understanding of a character. A “foil” is a specific term for a character who provides contrast to the protagonist, enabling you to draw attention to certain aspects of their personality or values.

Or perhaps the character you’re focusing on acts a certain way with a particular person they don’t with anyone else, enabling you to show qualities that you wouldn’t otherwise be able to.

Relationships can also influence the plot or the character arc. Other characters can prompt them to act or change in a certain way rather than always needing to rely on external events or internal shifts.

Finally, relationships enable you to make your characters feel more realistic. If everyone your character meets likes them, readers might become frustrated. If some people either dislike them or take a while to warm up to them, it will feel much truer to life.

Refine Plot and Pacing

Here are some tips for making your plots even more satisfying and ensuring your pacing never leaves a reader floundering.

Add Conflict

Can you introduce more conflict? (Spoiler alert: the answer is usually yes.)

Contrary to the name, this doesn’t have to be a battle or an argument, though those are both excellent sources of it. Instead, it’s anything that comes between a character and what they want.

Conflict drives the plot forward and builds tension for the reader. It also pushes characters to develop by challenging them and forcing them to change, adapt, or push back.

Conflict can be internal. This involves a character struggling with their own thoughts, feelings, beliefs, morals, desires, and/or self-image.

It can also be external. That could take the form of circumstances, society, or other people exerting pressure on the character.

You usually want a combination of internal and external conflict, and the two can play off each other.

In a novel, introducing different types of conflict adds tension to a story and makes the character’s emotional journey more satisfying and believable. Think about additional ways, big and small, you could challenge your characters and what that might spark.

For a short story, it might be sensible to focus on one central source of conflict, but you can explore that in different ways, both internally and externally.

Nail the Stakes

The stakes are the consequences for your characters in terms of what they stand to gain or lose due to what happens in the story. They could range from your character not getting a promotion to the end of the world.

As with conflict, stakes can be external and internal, and you generally want a mixture. They can also be interconnected—for instance, with external stakes, like a threat to the world, we need to understand what that means for the character personally.

The stakes need to rise as the story progresses to ramp up the tension and keep a reader’s interest. Stakes can be different for different characters, so you can experiment with raising them for different people at different times.

Like with motivation, a reader needs to understand what the stakes are at every point of the story, so they know why they should care about what’s going on and why it’s so impactful for the characters.

Tighten Up the Pacing

Pacing has a huge influence over a reader’s experience of a story, so it’s worth tinkering with it to get it just right.

Aim to strike a balance between action and more reflective moments. You want to give the reader enough excitement to propel them through but not so much that they don’t have time to breathe, take stock, and process what’s going on.

Something that can influence the pacing is where you choose to summarize action through narration and where you depict it directly with a scene. Dialogue can also speed up the pace, while description often slows it down.

You can also influence pacing with the length of your sentences. Short, punchy sentences maintain momentum through action scenes, and longer, more complex ones help to moderate the pace during quieter moments.

These tips can apply to short stories too. However, you need to be particularly economical about what you include in a short story. It’s even more important for every scene, paragraph, and sentence to pull its weight.

That being said, short stories are also a great place to experiment with untraditional forms and/or pacing. Your reader is likely to give you a little more leeway because you’re not asking them to stick with you for an entire book.

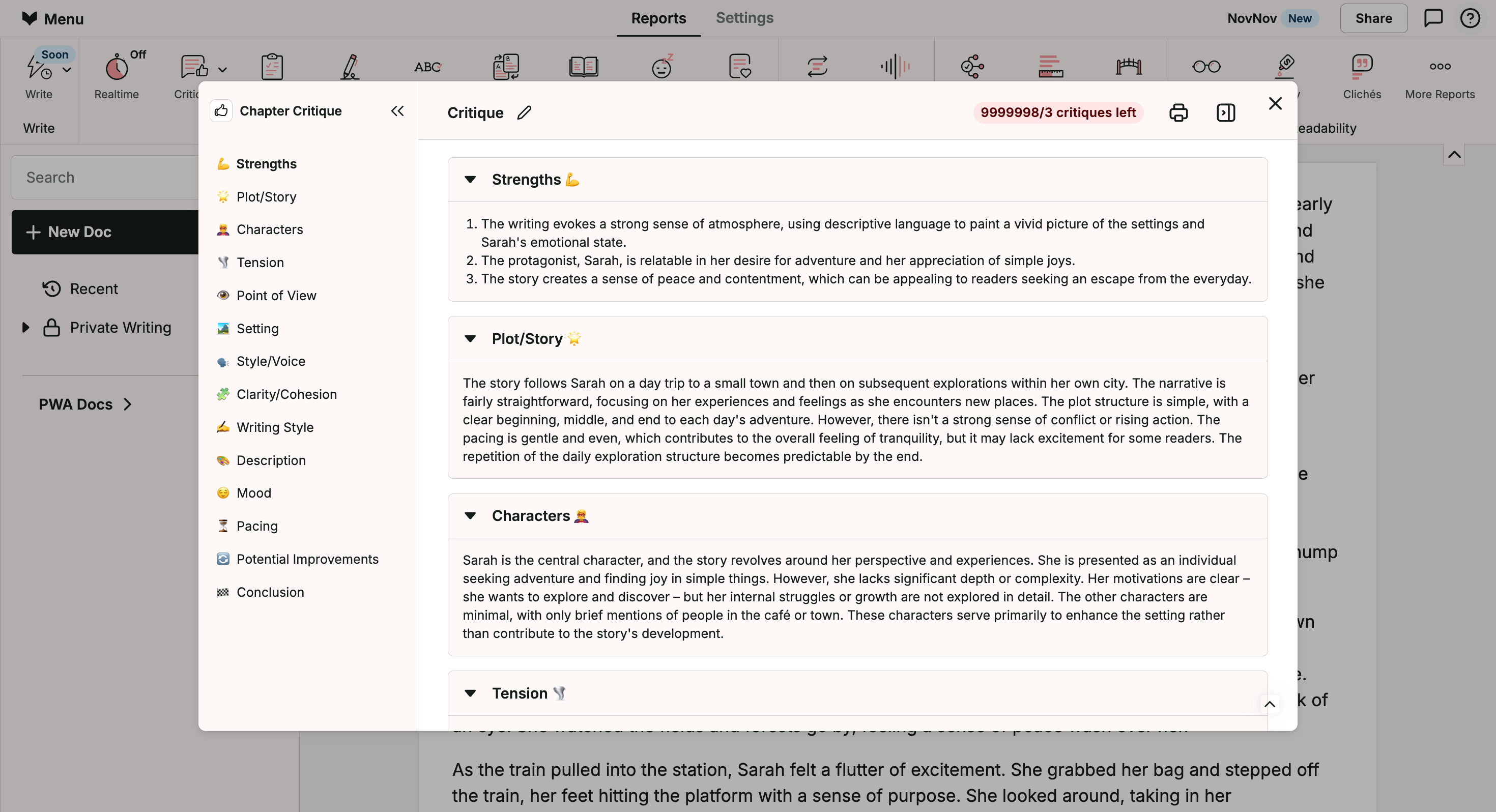

Pacing can be hard to judge from the inside. ProWritingAid’s story editing tools can offer quick, objective feedback on how your story is flowing. Try Manuscript Analysis for entire novels or Chapter Critique for chapters and short stories of under 4,000 words.

End It Well

Endings are notoriously difficult. Too neat, and people might feel cheated. Too messy or lacking in resolution, and they’ll feel frustrated or let down.

Most endings flow from the climax (where the central conflict comes to a head), through falling action (where you wrap things up), to the denouement (the final resolution). While not all books neatly fit this pattern, it still gives you a handy way to think about it.

Be wary of “deus ex machina” endings: where the problem is solved by an unlikely event.

They are unsatisfying because they feel unrealistic. Readers, having watched the characters struggle for an entire book, also want to see them win for themselves.

One way to mitigate this is to carefully foreshadow it earlier so a reader doesn’t feel it’s coming out of nowhere. If you can give your characters some form of agency in the climax though, it’s likely to land better.

With the falling action, you want it to be satisfying but not too meandering. Pacing is still vital here so that you don’t frustrate a reader. Even though you’re winding down, it’s possible to include dramatic moments so long as the overall tension is diminishing.

As for the denouement, the important thing to remember is that it doesn’t have to be a complete resolution.

Think about how you can tie up most of the loose ends but leave something up to the reader’s imagination.

You could also aim for mixed emotions. If it’s mostly happy, could there be a slight sting in the tail somewhere? Maybe a character has lost something along the way. If it’s a sad ending, could you introduce a little spark of hope?

It could help to think about your characters and the journey they’ve gone on here. For example, you might decide that your romantic couple aren’t actually ready to commit to a relationship yet, but you could leave a reader with reason to hope they will later.

Obviously, things are different if you’re writing a series: you may end on a cliffhanger, not long after the climax, to convince readers to keep reading. If you’re writing a romance or a comedy, then a completely happy ending might also not be out of place.

With a short story, you don’t have as much room to resolve things. Instead, a good approach is to opt for something that will linger in a reader’s mind, like a striking image or thought.

Sharpen Your Style

Here are some ways to improve the actual words on the page.

Show, Don’t Tell

You’ve probably heard this one all too often, but what does “show, don’t tell” really mean?

It refers to showing things to the reader rather than informing them about them. It’s much more satisfying for a reader to see them in action and join the dots for themselves. They’re also able to step more fully into the world on the page.

One way to do this is to use indirect characterization techniques. Show aspects of a character’s personality through their actions or their dialogue rather than describing them.

If they get angry easily, don’t just tell a reader that directly. Put them in a scene where a reader can see their temper mounting through what they say and how they behave.

The same goes for relationships. If two characters are falling in love, dramatize it on the page through the way they interact and how they think about each other.

You can also reveal details about the setting by having the characters interact with it. Rather than telling a reader it’s cold, have your character pull their coat tighter around them.

Of course, sometimes you do need to tell. Showing too much can also mean people get bogged down in unnecessary detail. This maxim just means that you should aim for more showing as a general rule.

Incorporate Sensory Detail

Sensory detail is a big part of “showing rather than telling” and of making your writing more immersive.

If you can appeal to all of a reader’s senses (sight, hearing, smell, touch, and taste), you can draw them into the scene. It makes it feel much more real and could help them relate to the point-of-view character if they can imagine feeling the same things.

You can also use it to help set the mood and/or to play on a particular emotion. Gloomy clouds or the smell of damp and decay could help you develop a creepy atmosphere.

As with any tool though, you need to use it strategically. Too much sensory detail will be overwhelming and could slow the pace right down. You also risk veering into purple prose: writing that’s so elaborate that it distracts from the story.

The best approach is to use it often but with a light touch, including just enough to ground a reader in the scene and add some interest.

ProWritingAid’s Sensory Report highlights where and how often you use sensory words. It helps you spot repetition and weak descriptors, and it can suggest alternatives to strengthen your writing. Sign up for free to try it.

Reduce Descriptive Dialogue Tags

A descriptive dialogue tag can be a lot of fun. But if characters are hissing, snarling, yelling, and crooning constantly, they might be doing the story a disservice.

It goes back to the idea of showing rather than telling. Ideally, readers should be able to work out how a character delivers a line based on the line itself, the situation, and what they know about the character already.

The same goes for using adjectives to jazz up tags; for instance, “she said angrily.” Again, you want your dialogue and characterization to do the heavy lifting where at all possible.

There’s also the argument that more straightforward tags like “said” and “asked” are easier for a reader to process in the moment, so there’s less chance you’ll distract them from the action on the page.

Of course, as with any other creative writing “rule,” this isn’t absolute. Sometimes you might find that a descriptive tag is necessary or will really enhance the speech. Just try to keep them for when they’ll pack the biggest punch.

Things to Try Outside of Writing

It might sound odd, but there are things you can do to improve your story writing that don’t involve writing or editing.

Read Like a Writer

You’ve likely heard the maxim that the best writers are readers, and it’s true. The best way to improve your writing is to saturate yourself with the writing of other people.

Obviously, it helps to read books in the genre or style you enjoy writing in. But you can learn valuable things from books that are completely different as well.

It helps to spend time thinking about what you read from a technical perspective.

Consider the plot of a book you just finished. How did the writer establish the stakes and then raise them? What forms of conflict were there?

Do the same with the characters. What emotional journey did they go on? How were they developed on the page? You could get very intentional about this and write a full character analysis, which enables you to really dig deep into what the author did.

Then there’s the style. Everything on the page (from the language to the perspective to the tense) was a choice the author made. Why do you think they went the route they did?

While you’re doing this, don’t just limit yourself to things you think the author did well. Considering things that didn’t land for you and diagnosing why that was and how you might go about fixing them could be just as worthwhile.

You don’t need to limit yourself to the written word. Thinking about films, TV programs, and video games from a plot and character point of view can pay off too. While some techniques and requirements will differ, it’s all storytelling, regardless of the format.

Observe

To be creative, you need to give your brain material to work with. Being tuned in to the world around you and seeing it like a writer is one of the best ways to do that.

Use your senses to observe your environment, like the smell of woodsmoke on the breeze or the sound of raindrops pattering on your jacket. Ask yourself how you could go about describing them to someone else so they could vividly picture them.

Listening to snatches of conversation on the street or noting how someone speaks while they’re being interviewed on the TV could help too.

While we all "um," "er," and repeat ourselves more often in real life than you can get away with in fiction, this still helps you to get a feel for natural-sounding dialogue and different voices.

Conclusion: Writing a Better Story

From understanding your characters’ motivations in more depth to introducing more sensory detail, there are plenty of ways you can strengthen your story writing skills.

“Writing a better story” is one of those quests you’re never going to finish, though; there will always be new things to learn and new techniques to try. The important thing is to pick one (or several) and start putting them into practice.

Whether you want help managing pace or identifying unnecessary dialogue tags, ProWritingAid has a range of tools that can help you hone your craft. Sign up for free and start exploring.